I first became aware of the

Neolithic stone face masks from Palestinian occupied territories by reading a

National Geographic article by Kristin Romey (2018) about the 16th

mask found. The sheer beauty, and the artistic intent which it displays

captivated me. As I delved deeper into subject, I found that there were more.

Approximately 16 in fact. Additionally, their ‘otherness’ and varied expressions,

imparting disparate emotions to the viewer, such as fear, shock and

occasionally joy or laughter, drew me in and elicited in me a host of questions:

“What did the artisans that made them mean to convey?” “What use were they put

to and what in context?” and “Did they have some religious or ritual meaning?”

You might, therefore, think that I

am about to embark on a story of entralling archaeological excavations carried

out under the scorching middle-eastern sun, by underpaid labourers or

university undergraduate students and their archaeologist supervisors, but

you’d be wrong. The truth is far darker and much more unsettling than that.

To frame the story in a

scientific framework, I’ll begin my story with those masks whose origin and

context is certain.

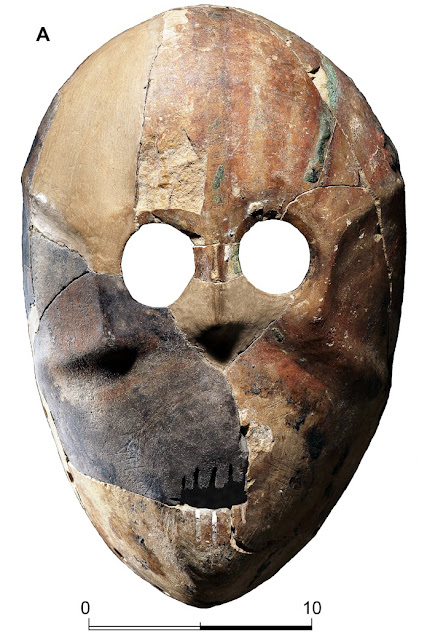

This is one of the 16 oldest masks ever made by man:

Nahal Hemar Cave Stone Mask, excavated in 1988 in the occupied west

bank of Palestine by archaeologists of the occupying state. Image credit: adapted

from Borrell et al. (2020). Original

caption reads:

Fig. 3. Some of the outstanding objects found in Nahal Hemar Cave: A)

stone mask.. [Photo A: Elie Posner].

Nahal Hemar Cave is a small chamber of about 4 ×

8m, with a narrow entrance on the west bank of the eponymous dry gorge in the

Judean Desert. It lies about 11km south of the town of Arad and at about 210m

altitude. The cave, after being discovered by locals and partially looted, was

excavated in 1983 by Bar-Yosef and Alon (1988), revealing one of the richest,

Pre-Pottery Neolithic B (PPNB) assemblages ever found in Palestine and the

Levant more widely.

Nehal Hemal Cave with the spoil from the 1983, excavations clearly

seen below the entrance. Image credit: Borrell et al. (2020).

The mask, and the partial remnant of a second were dated by 14C

dates, Bar-Yosef and Alon (1988) between 7900 and 7100 cal. BC, which puts it

in the Middle/Late Pre-Pottery Neolithic for the region. The mask is therefore

one of the earliest face-masks ever found from any site worldwide. As such, it,

along with the 15 others found in the area, is of tremendous significance for

humanity. At nearly 10,000 years old it, in my opinion rates as one of the

greatest pieces of portable art from the period in question. It is now housed

in the Israel Museum in Jerusalem.

In addition to the stone masks a myriad of unique and precious objects

was also found: modelled skulls [that is skulls plastered in asphalt], remains

of an anthropoid statue, bone figurines, well-preserved organic remains such as

mats, wooden beads, basketry, knotted netting and twined fragments of linen.

Flint tools, as well as numerous blades of a type unique to the cave: the ‘Nahal

Hemar knife’ [large and pointed blades with two proximal opposed notches], a complete

sickle, made from bone with flint inserts, beads of stone and plaster and

seashells from the Red Sea and the Mediterranean.

‘Modelled’ skull from Nahal Hemar. The material used to cover the

detached human skulls was asphalt. The bodies to which the three skulls

recovered belonged, were also buried in the cave. Image credit: Yakar and

Hershkovitz (1988).

Nahal Hemar ‘knives’. These stone tools, unique to the cave were often

found broken and/or burnt, what their purpose is unclear, but ritual usage

seems to be a strong possibility, considering the makeup of the assemblage

overall.

The mask of second-most note is that from Horvat

Duma.

The Dayan Mask, ploughed up near Horvat Duma and subsequently sold to

the then, eponymous Israeli defence minister. Image credit: Israel Museum.

It’s history is documented by Hershman (2014): “Our intriguing story

of the most ancient masks in the world opens with the stone mask, [discovered and] purchased in 1970 by

Moshe Dayan (who was Israel’s Minister of Defense at the time) in Kefar Idna,

near Hebron. Shortly thereafter “the Dayan Mask,” as it is called, was exhibited

at the Israel Museum. Following Dayan’s death in 1981, Laurence and Wilma

Tisch, New York, acquired the Dayan collection of antiquities and donated it to

the Israel Museum. Since then the mask has been part of the Israel Museum Collection

and is one of the universal treasures displayed in the Museum’s permanent

exhibition of prehistoric cultures.

This mask is officially known as the “Mask from Horvat Duma,” named

after the place it was found, which is next to Hebron. However, based on

evidence that reached us it appears that the mask was actually unearthed by a

farmhand who had been ploughing a field north of Horvat Duma, on the outskirts

of the village of el-Hadeb. In his book Living with the Bible, Dayan writes: “I

was fortunate to acquire a ritual article from this region, a magnificent mask

... The marvel, apart from its age, lies in its facial expression. It has circles

for eyes, a small nose, and prominent grinning teeth. It is a human face, but

one that strikes terror in its beholder. If there is any power in the world

able to banish evil spirits, it must assuredly dwell in this mask … Before

handing it to experts at the government department of antiquities for their

study and confirmation of the dating, I was anxious to inspect the site where

it was found … I examined the ploughed soil and spotted bits of bone and

fragments of stone vessels between the clods of earth in the furrows.”

Following in Dayan’s footsteps, a local antiquities inspector from

Hebron, archaeologist Jibril Srur, set out for el-Hadeb. In the trial

excavations he conducted there, flint and stone tools, bones, lumps of ochre,

and the remains of early structures that had been damaged by the tractor came

to light. The site’s area was estimated at around 2.5 acres. All these finds

attest to the fact that in the Pre-Pottery Neolithic B Period, some 9,000 years

ago, a large village existed at this site.”

It is interesting to note that, like the masks from Nahal Hemar, the Horvat

Duma example also comes from the occupied West Bank. All sites and museums in

the occupied lands fell into the hands of the Israelis after the Six Days War.

To understand the scope and completeness of the cultural appropriation that

took place, it is worth taking a look at an academic study of the record of

Israeli archaeologists post 1967.

Excepts, from Greenberg and Keinan (2009): “The six-day war of June

1967 marked the beginning of a process that was to revolutionize the

archaeological investigation of the central highland regions, leading to the

addition of thousands of sites to its inventory, hundreds to the list of its

excavated places, and changing some of the central paradigms of archaeological

interpretation of its history.

..In Israel, the fields of archaeology and historical geography had

long been linked, and academics in both fields had an intimate and mutual

relationship with military historians and with the Israeli Defence Force (IDF)

itself. In 1956-7, during the brief conquest of the Sinai peninsula, limited

surveys and excavations were carried out with IDF assistance by the pioneer of

the archaeological survey in Israel, Yohanan Aharoni, this was to be a model

for future work in Israel’s battlegrounds. In 1967, archaeologists entered the Palestine

Archaeological Museum almost in tandem with the troops.

Immediately after the war, on the 15th of June 1967, the

Archaeological Council was convened: at the top of its agenda were the

protection of sites in the newly occupied areas and the fate of the Museum,

which had recently been nationalized by Jordan shortly after the occupation of

the West Bank in 1967, the “Emergency Survey” of the West Bank, and the Golan (so called, in view of the

impending return, as it was thought, of the occupied territories to Jordan and

Syria) was put into motion. Within a few months the surveyors were able to

submit a preliminary report, presented at a meeting in the residence of the

President of Israel: This survey focused on sites already identified on maps or

in the Mandatory Schedule of Sites as possible antiquities sites..

It was to be followed by a long line of surveys, many of which emerged

from the crucible of Israeli survey methodology at Tel Aviv University.

These surveys, which dramatically transformed our knowledge of the archaeological

resources of the West Bank, were initiated in 1978, after it became clear that

Israeli presence in the West Bank was not a passing phase, this realization

corresponded with political changes in Israel and the invigoration of the

settlement policy in the West Bank. The surveys have recorded, to date, a total

of approximately 6000 sites—a 600% increase in relation to the number of sites

recorded in 1967…

Gradually, Israeli academics began to initiate research-oriented

excavations, often merging with survey work. This trend reached its apex during

the second decade of occupation, from 1978-1987, when funding for work in the

West Bank became available due to the promotion of Jewish settlement activity

by the Israel government.”

Whilst the situation has been somewhat ameliorated between the

Israelis and the Palestinians, since the 1993 Oslo accords, actual involvement

of the Palestinians has been limited due to the chronic lack of funding imposed

by the economic conditions brought about by the Israeli occupation.

Greenberg and Keinan (2009) again: “The signing of the Oslo accords in

1993 introduced a new phase of activity: Because the Oslo accords, as

negotiated in bilateral interim agreements, called for “[the transfer of]

powers and responsibilities in the sphere of archaeology in the West Bank and

the Gaza Strip… from the military government and its Civil Administration to

the Palestinian side.. a sense of

urgency arose regarding areas scheduled for withdrawal. The most visible of these

pre-implementation activities was “Operation Scroll”, a Staff Officer for

Archaeology SOA-IAA (Israel Antiquities Authority) collaborative effort

conducted in late 1993-early 1994 in order to pre-empt possible looting

(according to the initiators) or retrieval by Palestinian archaeologists

(according to critics) of epigraphic material from Judean Desert caves in the

area of Jericho and the northern Dead Sea shore.

After implementation, when parts of the West Bank were transferred to

the authority of the Palestinian National Authority and its Department of

Antiquities (the PDA), pressure on the archaeological sites within areas still

controlled by the SOA did not abate. This was caused, on the one hand, by the

closure policy that led to increasing economic hardship in the West Bank and

the concomitant rise of subsistence

looting. On the other hand, the construction of the Separation Barrier in

the first decade of the new millennium threw dozens of archaeological sites in the

way of destructive development, necessitating dozens of new salvage

excavations. In April 2008, at the 34th Archaeological Congress in Jerusalem,

the SOA characterized the members of his unit as the “last archaeologists” in

the West Bank, signifying that — in his perception — few antiquities of significance

would survive the disorder that would reign after the dissolution of the unit

(presumably, in the event of Israeli withdrawal and the establishment of a Palestinian

state), and that there was no significant Palestinian professional infrastructure

that could take over the SOA’s responsibilities.

…the SOA has remained very active in the last decade of recorded work,

carrying out more than 270 excavations at 190 sites. The total number of SOA licenses

for excavation and survey issued between 1967 and 2007 was 1148, of which at

least 820 were carried out by the unit.

A few words may be in order regarding archaeology in the Palestinian

National Authority, although work carried out by its Department of Antiquities is

outside the purview of this report. In a review of the emergence of a Palestinian

school of archaeology, Ziadeh-Seely (2007) describes the ideological and institutional

background to the creation (and

subsequent temporary demise) of the Institute of Archaeology at Birzeit

University, emphasizing the attempt to create a multi-cultural approach to the

past.

Al-Houdalieh (2009) has recently complemented this description with a

thorough assessment of the present state of archaeological studies in the

occupied West Bank. These publications establish the existence of an

independent Palestinian approach to archaeology, initiated in the late 1970s

and surviving, if not thriving, at the present.”

It is therefore clear, that the Israeli’s have systematically sought

to find, recover and remove to Jerusalem every antiquity they could discover.

Not only that, by their policy of closure, of the West Bank in particular, they

have deliberately made the Palestinians economically destitute thus fostering

the subsistence looting highlighted above. Worse still, the narrative of whose

ancestors were responsible for the creation of some of the greatest art of the

Neolithic has been substantially re-written in favour of a group who are

largely immigrants – the Israelis.

Of the 16 masks known to exist, three are in the possession of the

Israeli state, one in a private collection within Israel (Tel Aviv), one in the

offices of the Palestine Exploration Fund in London, one in the Musée Bible et

Terre Sainte, Paris, one (partial) mask in a Jordanian museum. The remaining 8 have been sold illicitly and

are housed in a family home of Michael and Judy Steinhardt, in upstate New

York.

Michael H Steinhardt is an interesting character with a chequered

career in hedge fund management, and a

somewhat sordid, family background. Son of Sol Frank Steinhardt, also known as

"Red McGee", allegedly New York’s leading jewellery fence. Whether he

ever reached so high in the criminal fraternity, is a moot point. Whatever the

true story, it is a fact that Red

Steinhardt was convicted in 1958 on two counts of buying and selling stolen

jewellery, and was sentenced to serve two 5-to-10 year terms, to run

consecutively.

In a Forbes’ (2001) article, much more detail was revealed about the

elder Steinhardt: “Sol was a compulsive high-stakes gambler and colourful New

York nightclub patron. He was also New York's leading jewel fence, a convicted

felon and pal to underworld figures such as Meyer Lansky and

"Three Finger" Jimmy Aiello. The night before crime figure Joey Anastasia

was rubbed out in the Park Sheraton barbershop in 1957, he and Sol were out on

the town gambling together.

The next year, Sol was convicted on charges of buying and selling

stolen jewelry and was sentenced to five to ten years in prison on each of two

felony counts.

Michael Steinhardt visited his father in prison, but saw it as an

obligation, since Sol had paid for Steinhardt's education at the University of

Pennsylvania's Wharton School – most likely with ill-gotten gains, Michael Steinhardt

suggests, in his autobiography, No Bull: My Life In and Out of Markets.

He also notes that when he was starting out on Wall Street, he was

lucky no one identified him as the son of a convict serving time at Sing Sing

and Dannemora, a maximum-security prison in upstate New York. Otherwise, such

white-shoe firms as Calvin Bullock, a mutual fund group, and Loeb

Rhoades, the brokerage firm that was a precursor to Merrill Lynch, would

not have hired him. In addition to an education, Sol gave his son envelopes

stuffed with $10,000 in $100 bills to put in the stock market. This helped

Steinhardt build his net worth to $200,000 at a young age. In effect, his

father was Steinhardt's first investment client.

Recent history, also

reveals similarities between the two men. Like father, like son, Michael Steinhardt

has also, had his own run in with the law. He and his firm were investigated,

with Salomon Bros. and the Caxton Group, for allegedly attempting to corner the

market for short-term Treasury notes in the early 1990s. In his autobiography he states "When

you're a target of the government investigation, it is very unpleasant,"

he says. He personally paid 75% of the $70 million in civil fines that were

part of settling the case with the Securities and Exchange Commission and

Justice Department – a mere fraction of the $600 million his hedge fund made on

the Treasury positions.

What did Michael Steinhardt, do with his dubiously acquired fortune?

Well he bought antiquities. Many hundreds by all accounts. In the course of

writing this blog post it has come to light that he now owns almost ALL the

known masks found by “subsistence looting”!

His collection of these Palestinian Neolithic masks now numbers 8.

Before we move on to those, several other masks discovered in the same period

as that from Horvat Duma are worthy of note. The mask now on display in the Musée

Bible et Terre Sainte, Paris, has an interesting history. Hershman (2014),

details its discovery:

“Józef Milik, a Catholic priest of Polish origin and a biblical

scholar, who was nicknamed “The Prodigious Priest,” was considered the

brightest member of the École biblique et archéologique française de Jérusalem

team working on the deciphering of the Dead Sea Scrolls. His single

contribution to the prehistory of the Land of Israel is less well known, and it

is doubtful that even he himself was aware of its importance.

During a field trip he took in the early 1960s, he purchased from

Bedouin near Hebron in the southern Judean Hills a stone mask as well as

several pottery vessels dating from the Middle Bronze Age, 3,600 years old.

Since the mask was sold together with the pottery, he assumed that it also

dated from the Middle Bronze Age and, consequently, that belonged to the

Canaanite culture. He gave the mask to the Catholic French research

organization, Bible et Terre Sainte, which was holding an exhibition in Paris

at the time on the material culture of the Bible. Owing to its artistic

qualities the mask became the star of the show. And indeed, in the publication

that accompanied the exhibition we read: “The most important work in the group,

which is unparalleled in any of the Palestinian collections, is the limestone

mask, whose power of expression arouses spectators’ admiration.”

The first description of the mask, which documents its details while

extolling the ancient stone carving, is still the most beautiful and

comprehensive portrayal of its special characteristics. “The mask is of a rare

perfection: An oval, youthful face, a broad forehead with prominent cheekbones

pointed at a straight, short nose. Round spaces take the place of eyes, and the

mouth is wide open as if to express deep, eternal astonishment. Above the eyes

traces of black paint are visible, which the artist used to indicate eyebrows,

since he could not carve them into the stone. The same makeup can be found on

the upper lip and the chin. Finally, six holes on each side and two in the

upper part (one is unfinished) were meant for suspending the mask. Nothing in

the art of that period exhibits the artistic proficiency that this artist attained in stone. Even though it was believed at that time that the

mask dated from the Bronze Age – a period thousands of years later than when

the mask was actually, made – it was defined as a breathtaking artistic

achievement.

Interestingly, Milik was indeed hard pressed to find parallels to the

mask within the Canaanite material culture, and he noticed the differences

between this mask and other masks from the Bronze Age, such as the clay mask

from Hazor. At the same time he managed to recognize the similarities between

the mask and the face of a Neolithic plaster statue head found in ancient

Jericho. Nonetheless, he rejected this observation owing to his impression that

the statue, with its eyes inlaid with shells, might represent a living person,

whereas the stone mask, he believed, was used in funerary cults. In his

opinion, its small size (18 x 14 cm) suggested that it did not cover the face

of the deceased but was rather attached to a pole and fulfilled a ceremonial

role.

The mask, along with the rest of the collection that Milik gave to the

organization Bible et Terre Sainte, moved to a small museum by that name that

opened in Paris under the auspices of Université Catholique de Paris. It

quickly became the most famous exhibit in its Biblical and Second Temple Period

collections, as it remains until today.

The French archaeologist Jean Perrot, who was

well-acquainted with the artistic and cultic finds of the earlier periods in

the Levant, determined that the mask was not Middle Bronze, but actually

belonged to the Neolithic Period. In his book, Syria-Palestine, he noted the

similarity between this mask, the Mask from Horvat Duma (discovered a year

after the opening of the museum in Paris), and the modelled skulls from Tell

Ramad in Syria and ancient Jericho, and he proposed that all these were

portraits of the dead.”

The mask from the Musée Bible et Terre Sainte, Paris. Photo credit

Hershman (2014). Original caption reads: Mask from the Musée Bible et Terre

Sainte | Unknown site, probably in the Judean Desert Pre-Pottery Neolithic B

Period, 9,000 years ago (?) | Limestone | 18 x 14 cm | Ca. 1 kg |.

The circumstances of the discovery of mask from er Ram north of

Jerusalem, now in the possession of the Palestinian Exploration Fund, London

are also described by Hershman (2014): “The purchaser of the mask, Dr. Thomas

Chaplin, a physician for the “London Society for Promoting Christianity Amongst

the Jews,” who directed the mission’s hospital in Jerusalem’s Old City in the

nineteenth century, was also a collector of antiquities. In 1881 one of the

women of the village of er-Ram northeast of Jerusalem sold him a stone mask. In

the article that appeared almost ten years later in the Palestine Exploration

Fund Quarterly Statement,54 he wrote that after he purchased the strange

ancient mask from the woman, the villagers, armed with rifles, chased him,

demanding that he return it, since they regarded it as a kind of amulet.”

The mask from er Ram, from Hershman (2014). OIriginal

caption reads: “Mask from er-Ram | Er-Ram, northeast of Jerusalem | Possibly

Pre-Pottery Neolithic B Period, 9,000 years ago. Chalk rich in iron mineral

veins | Ca. 20 x 18 cm | 1.8 kg |. Stylistically different from the other mask,

with features recalling a living human face instead of skulls, this mask may

represent a different tradition of mask-making or an unfinished mask.

Mask in the collection of Oded

Golan, Tel Aviv. This mask has an unknown provenance, but is very close in

terms of material and style to the other masks of this group. Thus assumed to

be ca. 9000+ years old, and made in the Neolithic, and obtained by illicit sale

of materials from subsistence looting.

The Oded Golan mask. Picture credit, Hershman (2014),

original caption reads: “Mask from a Private Collection in Israel | Provenance

unknown | Pre-Pottery Neolithic B Period, 9,000 years ago Limestone |

Dimensions unknown | Collection of Oded Golan, Tel Aviv.

Returning now to the remainder of the known masks, all in

the possession of Michael Steinhardt, they are as follows:

The “Watching Mask”.

The Oded Golan mask. Picture credit, Hershman (2014),

original caption reads: “Mask from a Private Collection in Israel | Provenance

unknown | Pre-Pottery Neolithic B Period, 9,000 years ago Limestone |

Dimensions unknown | Collection of Oded Golan, Tel Aviv.

Returning now to the remainder of the known masks, all in

the possession of Michael Steinhardt, they are as follows:

The “Watching Mask”.

A

slightly threatening mask with unsettling eyes. Hershman (2014). Original

caption reads: “Watching Mask | Unknown site, southern Judean Hills |

Pre-Pottery Neolithic B Period, 9,000 years ago. Chalk | 20 x 16 cm | 1.8 kg |

Collection of Judy and Michael Steinhardt, New York.The Large Mask

The Large mask with its almost

expressionless face, seems to say “the only thing the dead know is that it is

better to be alive”. Picture credit, Hershman (2014). Original caption reads: “Large

Mask | Unknown site, southern Judean Hills. Pre-Pottery Neolithic B Period,

9,000 years ago. Chalk | 29.5 cm x 16 cm | 2.2 kg | Collection of Judy and

Michael Steinhardt, New York.

Debby Hershman holds up the Large Mask in her laboratory, during the

preparation for the exhibition of the masks. In interview Zion (2014) for the

Times of Israel, she hazarded that “The people who created this artwork were

among the first humans to abandon nomadic life and establish permanent

settlements. Because the masks predate writing by at least 3,500 years, there

is no record of their usage. Based on years of attribute analysis of their

iconography, however, Hershman believes that the carved limestone masks were

used as part of an ancestor cult, and that shamans or tribal chiefs wore the

masks during a ritual masquerade honoring the deceased.”

Image credit: Zion (2014). Original caption

reads: “Dr. Debby Hershman, curator of prehistoric culture at the Israel Museum,

holds up a neolithic mask in the museum’s laboratories.”

The Expressive Mask

To

me the Expressive Mask shows a laughing face. If these masks are meant to show

the face of the deceased, then perhaps the person had a happy life and was one

of those people that met each day with a smile? It makes me wonder whether the

masks were made for individuals and if so did sculptor(s) attempt to embody

some aspect of the deceased personality in the mask they carved? Picture credit

Hershman (2014. Original caption reads: “Expressive Mask | Unknown site,

southern Judean Hills | Pre-Pottery Neolithic B Period, 9,000 years ago. Finely

crystalline limestone | 16.5 x 12 cm | 0.7 kg | Collection of Judy and Michael

Steinhardt, New YorkThe Solid Mask

The

Solid Mask recalls that from er Ram above. Whether, it too, represents a

different, artistic tradition, is unknown. Picture credit Hershman (2014).

Original caption reads: “Solid Mask | Unknown site, southern Judean Hills |

Pre-Pottery Neolithic B Period, 9,000 years ago | Finely crystalline limestone

| 21.8 x 13.2 cm | 2.9 kg | Collection of Judy and Michael Steinhardt, New York.”The

Miniature Mask

Another smiling mask, but this time of very small size. Once again,

the mask triggers a cascade of thoughts and emotions. I wonder, does the face

relate to an actual person? Considering its size and expression, perhaps it was

a baby or small child? But with the context unknown and probably destroyed by

the looters, I guess we’ll never know. It is so frustrating that people like

the Steinhardts are willing to pay for these objects and thus be complicit in

the destruction of irreplaceable Neolithic sites.

Were these unprovenanced masks found in a ritual setting like Nahal

Hemar? If so what were the relationships between this mask and the other

objects which, may have been found? Once again, the answer is we’ll never know.

Picture credit Hershman (2014). Original caption

reads: “Miniature Mask | Unknown site, southern Judean Hills | Pre-Pottery

Neolithic B Period, 9,000 years ago.”

The

Chief’s Mask

Two views of the Chief’s Mask. The expression, like that of the Large

Mask is rather bleak. Again, I wonder, what was the sculptor trying to convey?

Additionally, the execution seems somewhat primitive. Is it older than some of

the others? Also and the surface patina seems smooth: was it regularly handled

as some sort of religious/cultic object?

Upper image credit Elie Posner, Israel Museum. This is in high

resolution and it is worth opening and zooming in to see the polished

toolmarks.

Lower image Hershman (2014). Original caption reads: “Chief’s Mask |

Unknown site, Judean Hills or southern Judean Foothills | Pre-Pottery Neolithic

B Period, 9,000 years ago Chalk | 19.5 x 15 cm | 1.3 kg | Collection of Judy

and Michael Steinhardt, New York.”

The Wondering Mask

To me this masks looks more primitive in execution, than some of the

others and seems very similar to the Chief’s Mask in material and the patina especially

on the lower part of the face. Considering two masks were found at Nahal Hemar

Cave, is it possible that these two masks came from the same site? Again, as

the owner was unwilling to explain the circumstances of the mask’s acquisition,

we will probably, never know.

Picture credit: Hershman (2014).

Original caption reads: “Wondering Mask | Unknown site, Judean Hills or

southern Judean Foothills | Pre-Pottery Neolithic B Period 9,000 years ago |

Dolomitic limestone | 21 x 13.5 cm | 1.6 kg | Collection of Judy and Michael

Steinhardt, New York.”

The Grinning Mask

A

third, rather primitive mask, but this time with a more pronounced expression.

Grinning? Yes, I’d go with that. Patina and ‘gut feeling’ put it close to the

last two stylistically and in terms of the base material from which it appears

to be made. Picture credit, Hershman (2014). Original caption reads: “Grinning

Mask | Unknown site, Judean Hills or southern Judean Foothills | Pre-Pottery

Neolithic B Period. 9,000 years ago | Chalk | 22.6 x 16 cm | 1.6 kg |

Collection of Judy and Michael Steinhardt, New York.”

The 16th Stone Mask

I’ll let Romey (2018), take up the story as she seems to have got the best

interview out of the team involved in the mask’s recovery:

“The stone mask was recovered several months ago by the authority’s

Theft Prevention Unit. A subsequent investigation led archaeologists back to

the “probable archaeological site in which the mask was originally found,” near

the settlement of Pnei Hever in the southern West Bank. The results of an

initial analysis of the mask were presented earlier this week at the annual

meeting of the Israel Prehistoric Society by Ronit Lupu, of the IAA’s

Antiquities Theft Prevention Unit, and Omry Barzilai, head of the IAA’s

Archaeological Research Department.

The newly discovered mask shares many characteristics of the others

found to date. These include a human-size face of soft, carved limestone with

large openings for eyes, a defined mouth, and holes drilled around its

circumference. The holes lead some researchers to suggest that the masks were

designed to be tied to a face or an object.

“It’s amazing, it’s beautiful,” says Lupu, who was involved with the

recovery of the mask and the identification of the site associated with its

discovery. “You see it and you want to cry from happiness.”

Along with their aesthetic appeal, the Neolithic stone masks are

scientifically important, created at a moment in history when people in the

region began to organise in settled communities, according to Barzilai, who has

analysed the find.

In this latest case, the unnamed person who discovered the mask led

Lupu to the find site. Conflicting accounts make it unclear whether the

artefact was voluntarily handed over to the Theft Prevention Unit or tracked

down. A surface survey of the site revealed flint tools dated to between 7,500

and 6,000 B.C., Lupu says. A preliminary isotopic and mineralogical analysis of

the mask shows that it came from that area.

Based on the hazy origins of the majority of the masks, Lupu

understands questions about authenticity. But she’s confident that the new mask

hails from the discovery site.

“I’m sure that this is the context for this

find,” she says. “I think when we publish the [final analysis of the mask], it

will be a done deal.”

Ronit Lupi in a variety of poses with the 16th

mask, stolen from Palestinian lands by the Israelis. Picture credit: Anon (2018).

Original caption reads: “Archaeologist Ronit Lupu told AFP it was an

"amazing find".

Thoughts on

the ‘recovery’ of the mask, from the Palestinian side paint a very different

picture. A feature piece in Middle East Eye by Vidal (2021), is scathing of how

the Israeli government continue to misappropriate items of Palestinian

heritage: “In 2014, the two masks owned by the Israel Museum were exhibited

together in Jerusalem with other masks from Michael Steinhardt’s private

collections for the first time.

“This is a

family reunion of the oldest surviving portraits of ancient man,” Debby

Hershman, the Israel Museum curator who organised the exhibition and conducted

research on the masks for a decade told the Israeli newspaper Haaretz. “We are

bringing them back home,” she added.

But it wasn’t exactly “home”. Although the Israel Museum was

built in the early 1960s on the lands of the Palestinian village of Sheikh Badr

and was designed to resemble an Arab village on the hill over Jerusalem, most

Palestinians are not allowed to visit it.

The majority

of the residents of the areas where most of the masks were found and taken from

- Palestinian towns and villages such as al-Ram, al-Hadeb, and the Hebron Hills

- were unable to see the masks the only time they were on public display

because of the restrictions placed on Palestinians entering Jerusalem.

The artists Basel Abbas and Ruanne Abou-Rahme were among those who

weren’t able to easily access the exhibition. In 2014, they came across the

Neolithic masks online while doing research for their work.

“We always had a fascination with masks and with anonymity, with being

anonymous as a political act,” says Basel Abbas. When they googled “masks +

Palestine”, they were expecting to find images of Palestinians wearing ski

masks at protests, but photos of the ancient masks exhibited at the Israel

Museum also showed up in the results.

“We were interested in how the museum was narrating these masks,”

Abbas tells MEE. The exhibition referred to them as “our masks” from “the

ancient Land of Israel”. In the exhibition’s catalogue, the borders of the West

Bank are erased and only terms like “Judean Hills” and “Judean desert” are

used, rendering Palestinians invisible.

“These masks don’t just pre-date Palestine and Israel, they pre-date

all religions. So for a single entity to try to claim this as part of their

national narrative is just taking mythology to a whole new level,” says Abbas..

In 2018, an Israeli settler found a mask [the 16th mask under discussion here] believed to be from

the same period in the southwest of Hebron, in the occupied West Bank. Even

though it’s against international law to remove cultural property from occupied

territories, the mask was taken by Israel’s Antiquities Authority.

"We have documented only what Israel confiscated following the

occupation of the West Bank in 1967," says Muhannad Sayel, director of the

national registry at the Palestinian Ministry of Antiquities. "We have

documented 20,311 artefacts [...] We are seeking to present a file to the

International Criminal Court on this issue to demand the restoration of

antiquities seized by Israel, and we are now at the stage of preparing this

file."

MEE reached out to the Israel Antiquities Authority for comment but

had not received one at time of publication.

The Israeli government maintains it is within its right to oversee

archaeology in the areas it controls in the West Bank. The military has its own

archaeological unit, which claims it is its responsibility to oversee

excavations and “protect” archaeological sites from illegal digging and the

smuggling of artefacts.

“The looting of Africa, the

Middle East and Asia by Europe is ongoing, and this is part of that framework,

a continuation of that mindset,” says Abbas. “Looting, whether it’s for

material wealth and natural resources, or history and ownership over narratives,

[is] an extension of what’s happening in Palestine today.”

I think those sentiments

summarise the actions of the Israeli Government pretty accurately. I could add

more, but the words of Palestinians, and how they feel about the theft of their

cultural and material heritage, in the form of these Neolithic Masks is far

more authentic than anything I could write. Enough said.

References

Anon (2018). Israel unveils 9,000-year-old mask from the

West Bank. BBC News online at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-middle-east-46376993

Borrell, F., Ibáñez, J.J. and Bar-Yosef, O., (2020). Cult

paraphernalia or everyday items? Assessing the status and use of the flint

artefacts from Nahal Hemar Cave (Middle PPNB, Judean Desert). Quaternary

International, 569, pp.150-167.

Gannon, M. (2014). World's Oldest Masks Show Creepy Human

Resemblance. At: https://www.livescience.com/44078-stone-age-masks-israel-museum.html

accessed 10.09.2021

Greenberg, R. and Keinan, A., 2009. Israeli archaeological

activity in the West Bank 1967-2007: A sourcebook. Jerusalem: Ostracon

Griffiths, S. (2014). The world's oldest masks: 9,000-year-old

stone 'portraits of the dead' go on show in Jerusalem. Daily Mail online at https://www.dailymail.co.uk/sciencetech/article-2573852/The-worlds-oldest-masks-9-000-year-old-stone-portraits-dead-Jerusalem.html

Hershman, D. (2014) Face to Face: The Oldest Masks in the

World. Catalogue for the exhibition. The Israel Museum, Jerusalem.

March–September 2014. Online at: https://museum.imj.org.il/exhibitions/2014/face-to-face/pdf/9.pdf

Lenzner, R. (2001). Michael Steinhardt's Voyage Around His

Father in Forbes Magazine published

online 8th Nov. 2001 at: https://www.forbes.com/2001/11/08/1108steinhardt.html?sh=4f696faf28b8

Romey, K. (2018). 9,000-year-old mask stuns archaeologists,

raises eyebrows. National Geographic at: https://www.nationalgeographic.com/culture/article/neolithic-stone-mask-discovery-archaeology-forgery#:~:text=The%20stone%20mask%20was%20recovered,in%20the%20southern%20West%20Bank.

Steinhardt, M. (2001). No Bull: My Life In and Out of

Markets. Wiley, New York.

Vidal, M. (2021). How the world’s oldest masks tell a story

of Palestinian dispossession. Middle East Eye at: https://www.middleeasteye.net/discover/palestine-ancient-masks-dispossession

Yakar, R. and Hershkovitz, I., 1988. Nahal Hemar cave: The

modelled skulls. Atiqot, 18, pp.59-63.

Zion, I. B. (2014). Israel reveals eerie

collection of Neolithic ‘spirit’ masks. Times of Israel at: https://www.timesofisrael.com/eerie-neolithic-masks-to-make-israel-museum-debut/