Reynard’s Cave is large, path-side cave on the Derbyshire side of the river Dove in Dovedale. The cave is now owned by the National Trust and features a single, tall chamber and small rear passage. The first official excavation was carried out in 1959 by Kelly (1960), although an unsanctioned excavation was carried out prior to 1926. I’ll come back to that later.

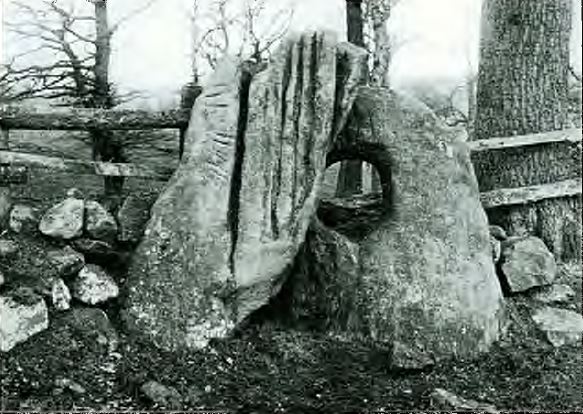

Reynard’s Cave from the approach path. Photograph, the author.

Finds included objects from the

Neolithic, Roman and Medieval periods, as well as animal remains. Finds listed

in the excavation report include potsherds identified as possible Peterborough

Ware, and two Neolithic flint scrapers; also Romano-British and Medieval potsherds. Although the excavation

report is fairly thorough, far more potsherds are listed by Branigan and Dearne

(1991). Subsequently some of the potsherds were attributed to the Iron Age. A

number of bone, lead and iron objects are likely to be Medieval, although a

Romano-British date cannot be ruled out for some of them. Lastly, a bronze

brooch of the Romano-British era was found.

The faunal assemblage included

cow, sheep, pig, horse, bear and other species, and is likely to be of various

dates.

Plan and section of Reynard’s Cave from Kelly (1960).

Neolithic flint scrapers from the 1959 excavation. Picture credit: Buxton Museum and Art Gallery (2014).

Thus the cave was regarded as an interesting one with a find record stretching over 6000 years. However, archaeologists remained aware that excavation had focused on a relatively small area and that the majority of the deposits were still untouched..

A heavy rainstorm forced a local climber to shelter in the cave one day in March of 2013. It may be that they sat on the comfortable, sheltered entrance platform for some while, watching the deluge and sheets of water begin to cascade down the arch, before becoming bored. Undoubtedly he began to explore the rest of the cave, whereupon his lit upon a small, dull grey object protruding from the soil. Imagine his delight, as his eager fingers unearthed an ancient coin, soon followed by three others! Being a moral person, he reported his find to the Portable Antiquities Scheme.

Eight of the Iron Age and Roman coins excavated from Reynard’s Cave, from the Portable Antiquities Scheme website (2013). Creative Commons licence https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/

When the owners of the land, the

National Trust, were informed, they organised a full scientific excavation of

the cave floor, which took place in October 2013. The joint enterprise

consisted of National Trust Archaeologists, headed by Rachel Hall, members of

the University of Leicester Archaeology Service (ULAS) and ex-servicemen from

Operation Nightingale.

Excavation of Reynard’s Cave in 2013, from ULAS news (2014).

A second view of the excavations in progress. Left middle Joanne Richardson, was part of the excavation. She commented: “This was the first archaeological excavation I’ve ever taken part in and it was brilliant. I was the first person to find a coin; a silver coin! It was so exciting and the experience working alongside archaeologists and other veterans was inspiring.” Picture credit: Ministry of Defense (2014).

The excavation carried out at the

point where the climber had found the original four coins, uncovered a marvelous hoard of twenty-two further Iron Age and Roman coins. Full details

are given on the Portable Antiquities Scheme Website (2013). The earliest coins

were three Roman silver, Dinarii, dated 118, 104 and 46BC; three Iron Age gold

staters; two gold/copper alloy staters; fourteen Iron Age silver coins; two

later Roman coins dating to around 330 AD and a counterfeit Henry III penny.

Iron Age silver coin (a ‘unit’) during conservation at UCL, here seen down a microscope. This is one of the coins listed on the Portable Antiquities Scheme website (2013), numbers 16-19. Image credit: Buxton Museum and Art Gallery (2014).

Also excavated were seven metal objects, the most important being a late, Iron Age brooch of the Roman 'Aesica' type with missing pin.

The 'Aesica' type brooch and part of the coin hoard. Image credit: Buxton Museum and Art Gallery (2014).

The complete inventory of finds

is hard to establish, as the report drawn up by ULAS remains unpublished. However,

their news page (ULAS 2014), is broadly informative regarding the finds:

“Because of the nature of the site it was decided to excavate in metre square

boxes digging down 10cm at a time. In this way, all finds could be recorded in

a 3-D fashion across the whole cave floor. Rather surprisingly it was

discovered that the cave deposits had been extremely disturbed by a combination

of root activity, animal burrowing (mostly badgers) and human activity. In one

case a sardine tin was found below some prehistoric pottery.

Despite this rather extensive

disturbance, a wide range of pottery dating from the prehistoric, Roman and all

the way through to modern periods was recovered. Fragments of cave bear jaw and

teeth were also found as were two human teeth. A Bronze Age flint arrow head,

lead musket and pistol balls, wartime .303 cartridges and a range of shotgun

cartridge cases demonstrated the advances in projectile technology over the

years.”

Other titbits from the reportage on the hoard also add depth to the story of the discovery and perhaps explain the reason behind the hoard’s deposition.

Urbanus (2014) “Archaeologists have retrieved a total of 26 gold and silver coins, all of which predate the Roman invasion of Britain in AD 43. While the bulk of the hoard is attributed to the Iron Age Corieltavi tribe, at least three coins are of Roman origin—the first instance of coins from these two civilizations having been found buried together. The location of the hoard is also unexpected, explains National Trust archaeologist Rachael Hall. “Coin hoards of this era in Britain have been found in fields and other locations but, as far as we know, not in a cave,” she says. “We may never know why the coins were buried here, but this discovery adds a new layer to what we are learning about Late Iron Age activity.”

Again Rachel Hall (from the Ministry of Defence (2014)) “The tribe is more usually associated with occupying areas further east during the Late Iron Age, so it is interesting that this find is where it is, in Derbyshire. Could this area have been a previously unknown power base of the Corieltavi tribe?”

ULAS (2014) “The Roman Republican and Iron Age coins are indicative of one or more hoards, which could therefore suggest that the cave was used as a ritual/deposition site during the 1st century AD. It would appear that coin hoards are extremely rare within caves, which adds even more to the mystery of the site. The Iron Age coins have been attributed to the Corieltavi tribe which is more usually associated with occupying areas somewhat further to the east of Dovedale during the Late Iron Age. The Corieltavi tribal centres are generally thought to be around Leicester, Sleaford and Lincoln so this hoard might represent an unknown area under Corieltavi influence or that the coins were deliberately transported to this special site.”

Live Science (2014): “Archaeologists previously found collections of coins like these in other parts of Britain, but this is the first time they have ever been discovered buried in a cave. The discovery of the coins was a surprise, because they were found at a site, which is located outside the Corieltauvi's usual turf. Archaeologists are still unsure how Iron Age coins were used, but it is unlikely they were used as money to purchase items. They were more likely used as a means for storing wealth, given as gifts or offered as sacrifice. The three Roman coins discovered predate the Roman invasion, so archaeologists believe the coins may have been given as gifts.”

Lastly, I return to a sentence

from Ariadne (2020): “A Romano-British coin hoard is reputed to have been found

at the site prior to 1926, but no details are known.” This comment is also

echoed on the ULAS (2014) news page: “There are vague reports in a 1926 guide

book of a small coin hoard being found there in 1925 but these finds have not

been seen since.”

This rang bells for me, as I have

researched the bone caves of Derbyshire for, a, number of years. For some time,

I could not draw to the front of my mind where I might have come across a

reference to it.

Finally it came to me in a rush:

Wasn’t G. M. Wilson’s Some Caves and Crags of Peakland published in 1926? I

read through my copy of the little tome and on page eleven came to the

following: “In the valley of the Dove, rock shelters and small caves can be

found which have only been casually examined. Reynard’s Cave lower down the

valley, has never had justice done to it either as a geological feature or as a

promising site for the antiquarian. The fine natural archway is a wonderful

sight, while the hoard of Roman coins accidentally discovered give a hint of

what may await systematic excavation.”

Rev. George M. Wilson was rather

quixotic character outside his ecclesiastical duties, taking a serious, and

somewhat obsessive interest in what he termed ‘cave digging’. To further his

pursuit of this ‘hobby’ he enlisted the help of local yeoman farmers, artisans

and miners as well as educated men from further afield. He seems to have been a

natural leader and fostered a feeling of joint enterprise amongst his acolytes,

not least by coining the name ‘Brotherhood of the Pick and Shovel’ for the

loose group.

Whilst some trustworthy, local

men were included, many were learned men and well-known names of the time.

These included J. L. Waterhouse; Dr R. Williamson; Geoff and Frank Hall; G. E.

Wilson (his son); H. J. Irwin; W. M. Rogers; R Brocklebank; J. Cringhall; Harry

Wright; L. Ramsbottom; A. J. Brain; Rev. D. G. Matthews; J. R. Duncan and a

young, Don Bramwell. He also excavated with the National Park campaigner and

environmentalist F. A. Holmes as well as the noted climber J. W. Puttrell.

His notable excavations included

Thor’s Fissure Cave and St. Bertrams Cave, upon which he gave frequent

lectures, not only to spread knowledge of the ‘Wonders of the Peak’ as he called

them, but for financial gain and to advertise his books.

He was also well versed in

self-publicity writing for, among others the Sheffield Daily Telegraph and contributing

interviews to national newspapers, such as the Daily Mail.

In his second book (Wilson

(1937)), he even confesses to making a present of one of the coins from St.

Bertram’s Cave to a journalist from the latter, aforementioned, publication!

I therefore believe that Wilson,

himself was the discoverer of the Roman Coin Hoard at Reynard’s Cave in 1925.

What he did with the booty, remains unknown. Whether he sold it surreptitiously,

or whether it was passed on to coin dealers as part of his estate upon his

death is an open question.

References:

Ariadne (2020) at: http://ariadne-portal.dcu.gr/index.php/page/13787380 accessed 04.07.20

Branigan, K., and M. J. Dearne. (1991). A Gazetteer of Roman-British Cave Sites and Their Finds. Sheffield: Department of Archaeology and Prehistory, University of Sheffield

Buxton Museum and Art Gallery (2014). Reynard’s Kitchen Cave hoard – Late Iron Age and Roman coins, at: https://buxtonmuseumandartgallery.wordpress.com/2014/07/10/reynards-kitchen-cave-hoard-late-iron-age-and-roman-coins/ accessed 18/07/2021

Kelly, J. H. (1960). Excavation of Reynard's Cave, Dovedale. Derbyshire Archaeological Journal; Volume 80 (1960). DAJ; Vol 80; pp.117-123.

Live Science (2014). Ancient Coins Found Buried in British Cave, at https://www.livescience.com/46693-ancient-cave-coins-discovered.html accessed 18/07/2021

Ministry of Defence (2014). Digging up the past, at: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/digging-up-the-past

accessed 18/07/2021

Open Government Licence: https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/version/3/

Portable Antiquities Scheme (2013) at: https://finds.org.uk/database/artefacts/record/id/555965 accessed 18/07/2021

ULAS news (2014). Treasures in the Kitchen: Archaeological investigation of Reynard’s Kitchen, Dovedale, Derbyshire, at: https://ulasnews.com/2014/10/20/treasures-in-the-kitchen-archaeological-investigation-of-reynards-kitchen-dovedale-derbyshire/ accessed 18/07/2021

Urbanus, J. (2014) The Dovedale Hoard. Archaeology vol. 67 no. 5

Wilson, G. H. (1926) Some Caves and Crags in Peakland, Wilfred Edmunds, Chesterfield.

Wilson, G. H. (1937) Cave Hunting Holidays in Peakland, Wilfred Edmunds, Chesterfield.