Discovered in 1848 by Captain Edmund Flint, or so the story goes. Flint, a British Royal Navy officer was overseeing the extraction of limestone to reinforce and rebuild the military fortress’s fortifications. The renovation of the stone walls had begun in 1841, after General Sir John Thomas Jones of the Royal Engineers conducted a study of Gibraltar's defenses and recommended improvements.

The stone for the

construction of Jones’ "retired batteries" was got, by the use of

gunpowder in quarries such as Forbes’ quarry. Why Capt. Flint, a naval officer

was overseeing the work and who the workers were, is unknown.

A local, likely apocryphal

story has it that, consequent to blasting Flint retired to a campaign chair in

the shade, while local Gibraltar men set about shifting the stone. Some while

later he was disturbed by a shout, put up by the workers: removal of blocks had

revealed a previously hidden cave without any apparent external openings. The

workers had looked in and apparently seen bones. This is what caused them to

send up alarums. Flint it seems, availed himself of a skull found in the cave.

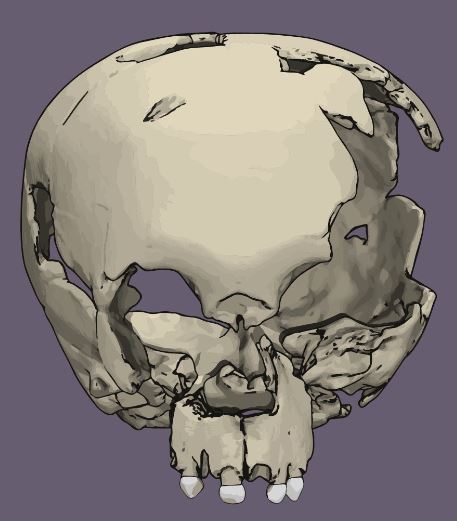

Gibraltar 1 cranium, a female and probably between 60,000 to 120,000 years old. Image credit: Pavid (2019).

At least the part of the story about the skull being found in a previously sealed cave was current among the learned men of the time. This is proved by the quip of George Busk (1864): “..in many respects, it [Gibraltar 1] is of infinitely higher value than that much-disputed relic, Neanderthal 1… [It] adds immensely to the scientific value of the Neanderthal specimen, if only as showing that the latter does not represent, as many have hitherto supposed, a mere individual peculiarity, but that it may have been characteristic of a race extending from the Rhine to the Pillars of Hercules; for, whatever may have been the case on the banks of the Dussel, even Professor Mayer will hardly suppose that a rickety Cossack engaged in the campaign of 1814 had crept into a sealed fissure in the Rock of Gibraltar.” Here Busk is referring to the theory of Mayer that Neanderthal 1 was a rickety Cossack. Mayer’s published views are well summarized by Schrenk and Müller (2010): “He confirmed the Neanderthaler's "rickety" changes in bone development... Mayer argued, among other things, that the thigh and pelvic bones of the Neanderthal man were shaped like those of someone who had spent all his life on horseback. The broken right arm of the individual had only healed very badly and resulting permanent worry lines due to the pain were the reason for the distinguished brow ridges. The skeleton was, he speculated, that of a mounted Russian Cossack, who had roamed the region in 1813/14 during the turmoils of the wars of liberation from Napoleon."

While Busk was humorously dismissive of Mayer’s interpretation of the other Neanderthal skull and remains, obviously something about the circumstances of the discovery, of Gibraltar 1, didn’t sit well with him. Undoubtedly, it was the condition of the Gibraltar 1 skull, with its sandy lime concretions that caused his disquiet. Busk, therefore determined to visit the find spot himself. Menez (2018), explains the circumstances of his subsequent exploration at Gibraltar: “Busk had planned to visit Gibraltar, noting in The Reader (Busk 1864a) that the purpose, with the full support of the Governor, Falconer and Busk (1865), was “to examine on the spot the conditions under which the different classes of fossils occur in the caverns &c”. The trip would wait, however, until after the Bath [BAAS] meeting, perhaps becoming even more important than hitherto after it became apparent that information related to the skull, which had engendered interesting debate in Bath, was scarce (Busk 1864b), Busk noting that: “The only information which we have been furnished respecting the situation in which it was found, is to the effect that it was dug up in the course of some excavations being made in what is termed ‘Forbes’ Barrier’… The exact locality, however, does not appear to rest upon any very certain evidence, and it may perhaps turn out that this interesting relic was derived from some other situation in the rock.” Busk, accompanied by Hugh Falconer and the British physician and travel writer Henry Holland, arrived in Gibraltar aboard the Poonah on 24 September 1864.” Busk, Falconer and Lieutenant Alexander Burton-Brown, thereafter visited Forbes’ Quarry. Brown (1867) later reported:

“..in October, 1864, examining with Professor Busk the slope of the old quarry of Forbes [sic] we found the matrix in which we believed the skull had been imbedded, which was a raised beach of about 100 ft. above sea level, and which was seen everywhere to be cropping out of the limestone slope, the inner portion of the beach being covered with broken pieces of calcareous rock, and the outer being broken off, disjointed masses being carried down by the crumbling masses of limestone; many subsequent visits confirm me in the opinion of this being the veritable matrix.”

Busk (1865) reporting

his observations at Forbes’ Quarry said “…from the matrix with which it [the

skull] was thickly covered, and which contained a very large proportion of

coarse rolled siliceous sea-sand, similar to that which is blown up in such

large quantities against the north-eastern end of the rock, it was apparent

that it had been lodged in the superficial part of the talus in which the quarry

is worked.”

Top: Busk’s photographs of the skull before removal of the matrix. Bottom: Busk’s photographs of the skull following partial removal of the matrix. Bottom: the skull today. Picture credit: Archives of the Royal College of Surgeons.

In 1865, mid-way

through his description of Gibratar 1, Busk received an urgent message to

attend to his close friend Hugh Falconer. Falconer had started to feel feverish

on the 19th of January. According, to, Murchison (1868) “the attack

developed into acute rheumatism, complicated with disease of the heart and

lungs, which proved fatal.” Busk was at his side as he died. Without Falconer, Busk

apparently could not continue, and he never finished his analysis of Gibraltar

1.

Within a year of Busk’s announcement that the Forbes skull was an object of immense scientific importance, it had retreated back into the shadows once again. The skull had been found but then quickly lost, tucked into a back room of Busk’s Royal College of Surgeons, collecting dust.

Other scientists

visited the site of Forbes’ quarry in latter, years to try to further clarify

the exact find spot. Results were

varied, and somewhat confusing.

Samuel William Turner, Surgeon to the Colonial Hospital in Gibraltar, it seems was encouraged, by Sir Arthur Keith, to seek what information he could on the Forbes Quarry site. Turner (1910) reported back: “the sloping talus which abutts on the perpendicular line above of the north face of the Rock at this point forms with the limestone the quarry referred to, and there is a distinct line of demarcation between the limestone and the conglomerate of the talus.” He then conjectured a possibility that has been perpetuated in the published literature ever since, describing that there was a small cave at the juncture between the conglomerate and the limestone, Turner surmised that “possibly the skull may have been found in this cave”. His description of the cave: “40 ft long, 8 wide” and requiring him to “stoop somewhat”, it showed no trace of osseous remains. Turner (1910), wrote again to Keith on 28 April 1910, informing him that “I fear we shall not be able to definitely locate to within a few yards the spot where the skull was found, or to say whether it was found embedded in the conglomerate of the talus at Forbe’s [sic] Quarry, or lying on the floor of the cave which exists in that quarry.”

Duckworth (1911),

also visited the quarry in 1910, with William Turner, Colonel Kenyon, and

others. His comments have been cited by many authors, such as Menez (2018): “the

skull was discovered in the brecciated talus is therefore quite possible.” However,

he also added the he “not understand why Dr Busk should have considered that it

[the skull] was derived from the superficial part.” and “For the talus is, in fact,

exposed vertically throughout a very wide extent.”

While quoting

Duckworth precisely, some details were left out, which, add more context. I’ll

come back to that later.

Duckworth (1910),

also contemplated that the cave might be a possibility. Having assessed the

area of Forbes’ Quarry to be composed of “more solid rock”, (compared to the

brecciated talus), it would be “excluded at once, were it not that just at this

spot it contains a cave.” He explored the cave from 13 to 17 September, but

found it contained “nothing save the very earliest and seemingly marine

deposits covered with stalagmite.”

The answer to his

query as to why Busk had opined that the Gibraltar 1 skull came from the

“superficial” part of the talus had been staring him in the face as he crossed

the floor of the quarry: the lime kiln. Living in the Peak District, as I do, I

have often observed that those labourers of the 19th century, when

fetching limestone to ‘burn’ in their kilns, naturally start with the material

closest to the kiln. In the case of Forbes’ Quarry, the brecciated slope must

have, been seen, as an excellent source limestone for produced quicklime

(calcium oxide). Therefore, in the 50 years, between Busk and Falconer’s visit

to the quarry, the local lime burners had obviously worked the slope of Busk

and Falconer back into the vertical outcrop of Duckworth. Whatever the position

of the skull in the talus, the point was made moot as on Christmas Day 1910, an

absolutely massive, landslip almost filled the quarry entirely.

Duckworth’s (1911) sketch of the Forbes’ Quarry Cave. Duckwoth’s comments, verbatim, form the original paper: “The actual appearance of the surface exposed by the workings in this quarry can be described more clearly with the aid of the sketch (Plate XL, Fig. 1), to which reference will now be made. The face that has been worked must have had much the same character throughout and it is quite peculiar, for the quarry lies exactly at the zone of union of the solid rock, shown in Plate XL, Fig. 1, to the right, with an extraordinary mass of consolidated debris known as the "brecciated talus."

That the skull was

discovered in the brecciated talus is therefore quite possible, but I do not

understand why Dr. Busk should have considered that it was derived from the

superficial part. For the talus is, in fact, exposed vertically throughout a

very wide extent.” This drawing makes it clear that the brecciated talus, was

to the left of the cave, and that the removal of it, presumably for lime

burning, did indeed remove a great deal of it, with the workings moving right

to left. A modern photograph shows the scene today:

Menez (2018), photograph of the location of Forbes’ Quarry Cave. Remnants of brecciated talus can still be seen on the left of the pillbox and solid rock to right. This, seems to me, to point to an origin for Gibraltar 1, higher up the slope, in a cave which, has been eroded away. Original caption reads: “Figure 4. The location of the cave at Forbes’ Quarry in 2016 (author’s photograph). The cave is still accessible from within the Second World War pillbox.”

Breuil (1922) the

area three times over the next decade (1911, 1917 and 1919) and commented on

Forbes’ Quarry and examined “the foot of

the slopes formed by the rocky rubbish of Forbes Quarry.” He noted that the

breccia was no longer in situ “on account of a gigantic landslide”. He also noted

that the “old marine rock-shelter of Forbes Quarry [the cave] was of no

interest, and had never contained deposits other than marine gravels and a

layer of stalagmite and clay, with the bones of very small mammals.”

On his perambulations, around the area, Breuil did notice that an intact talus slope fronted Devil’s Tower Cave nearby. He was unable to excavate this himself, and recommended it to his student, Dorothy Garrod, as a likely place to seek further Neanderthal remains.

Now I must step back

many years to look at how archaeologists classified the Gibraltar 1 skull. The

first to give a detailed description was Broca (1868). He gives some

measurements and makes a few comparisons, which while not a formal diagnosis,

highlighted the differences between it and save but one other, fossil skulls

excavated up to 1868.

His description reads

thus:

“3° Another

prehistoric skull. The last two photographs sent to us by Mr. Busk represent

the face and profile of an extremely curious skull, which also comes from the

vicinity of Gibraltar, but which appears much older than the previous ones [from Genista cave]. The date of this

skull is also undetermined! It was not found in caves, but in the surrounding

soil. It was buried in a very compact, very adherent matrix, from which we

could only release with the greatest difficulty.

A large part of the

vault, between the bregma and the lambda, is absent. What remains of the vault

presents a slight degree of asymmetry which seems to be the consequence of a

posthumous deformation. I cannot give geological information on the ground from

which this skull was extracted. According, to Mr. Busk's communication to the

Norwich Congress, no characteristic fossils were found there; but everything

indicates, moreover, that this site is extremely old, and the skull itself

presents characteristics of inferiority, which fully confirm this view, and to

which Professor Huxley has drawn the attention of members of Congress.

The absence of part

of the vault and the fragments of gangue which still adhere to several points

do not allow the diameters to be rigorously measured in order to determine the

cephalic index, but it is evident that this skull is very dolichocephalic. It

is not very bulky; but its walls are very thick; around the perimeter, the

thickness of the parietals amounts to 9 and a half millimeters. The

superciliary arches form a considerable projection on the profile; the forehead

is small and very elusive.

The face is broad and

prognathous, the opening of the anterior nostrils is very wide, the eye sockets

are enormous and almost rounded in shape. Their width is 44 millimeters, their

height 39, their depth 51. The width of 44 millimeters is the largest I have

found so far on a human skull; it is exactly that of the orbits of the old man

of Les Eyzies, but in the latter case the enormous transverse development of

the orbital openings coincided with an excessive reduction of the vertical

diameter (27 millimeters), while on the Gibraltar skull the height of the orbit

is on the contrary exaggerated. As a result, despite the extreme width of the

orbit, the orbital index rises to 68.83, an enormous figure, nearly 4 percent

higher than the maximum that I have encountered so far in man. The interorbital

space is, moreover, very wide, 23 millimeters below and much larger above.

It follows that the transverse development of the upper part of the face is very great. On the front photograph, we do not see the temporal region, entirely masked by the outer edges of the eye sockets; the external orbital process forms a considerable protrusion, above which the forehead sharply narrows. This forehead is also extremely low, and it is so small in all its dimensions, especially when compared to the face, that it resembles that of apes. Professor Huxley has pointed out the simian shape of the dental arch, which tapers noticeably behind, like a horseshoe. The Company is already aware of the importance of this character, to which, for several years now, Mr. Alix has drawn its attention. Another simian character that Mr. Huxley insisted on is the absence of the canine fossa, which is replaced by a convex surface! Mr. Huxley has so far not seen this conformation on any other human skull, and I believe it can be said that it is not found on none of the skulls in our museum.”

The next scientist to

analyse the Gibraltar 1 skull was Sollas (1908). His work built on that by

Huxley (1863) and more especially Schwalbe (1890; 1901a; 1901b; 1904; 1906).

The extremely detailed work discusses the problems of measuring skulls

accurately including that of establishing a baseline from which to measure and

what equipment to use. Sollas measures, computes and compares many lengths,

radii and angles of curvature, with reference to a collection of Australian

skulls, Neanderthal 1, the Krapina remains, the skulls from Spy, more recent

humans and certain great apes. In short the work, running to 60 pages, with

copious illustrations and tables of data is a tour de force, the thoroughness

of which, many modern papers do not attain.

Sollas comments: “One

of the most important, as it is certainly one of the most striking, peculiarities

of the Neandertal calotte is the frontal torus, the confluent supra-orbital

tori; this is distinguished not merely by its magnitude, though this is

excessive, but still more, as Schwalbe points out, by the continuous and

uniform character which it maintains throughout its whole extent. In the skulls

of Australian natives two regions may usually, though not always, be

distinguished in each supra-orbital torus, a more or less shallow groove which

takes an oblique course, separating an

outer temporal from a

more median supra-ciliary region; in the Neandertal group this groove is

almost, if not entirely, effaced.” Sollas goes on to conclude: “Briefly

summarising our results, we may remark that the skull of the Neandertal race

possesses many features in common with certain flattened skulls which are met with

among tribes inhabiting the southern part of Australia ; it differs from them in

breadth, being markedly broader, in the characters of the glabellar region, and

in thickness. The face of the Neandertal race on the other hand is peculiar.

The large round, widely open orbits, the projecting broad nose, the retreating

cheek bones, the absence of any depression beneath the orbits, the long face,

and the low degree of prognathism distinguish it in the clearest manner from

the Australian. “

While Sollas (1908),

does not address the thorny issue of nomenclature, he has established two very

clear points:

1. Gibraltar 1.

Belongs to the ‘Neanderthal race’, since referred to Homo neanderthalensis.

2. More importantly, Sollas has established a system of measurement and comparison for human skulls and Neanderthals in particular.

Palate of Gibraltar 1 skull from Sollas (1908). Original caption reads: Fig. 24. – Outline of the palate of the Gibraltar skull, drawn with an orthopter. ( x 2/3.)

One last point regarding the actual circumstances of the discovery of Gibraltar 1 is given in Menez (2018): “It may be that an old lady who lived in the small fishing village of Catalan Bay, very near Forbes’ Quarry, was the last living person with first hand knowledge of the skull’s discovery. In his letter to Sir Arthur Keith of 28 April 1910, Samuel William Turner [Turner 1910], reported that: Today I drove round the Rock to Catalan Bay on the Eastern Side to interview an old woman of 84 who was said to know something about the finding of this skull, but I found the old lady almost in her dotage, and could not get reliable facts from her. The lady would have been 22 years old in 1848, and 38 during Busk and Falconer’s visit in 1864. Had she been known to them, we might have a much fuller history of the Gibraltar Skull.”

The information, or

rarther lack of it, that Turner gained from the old lady of Catalan Bay,

perhaps relates to the apocryphal story I presented at the beginning of this

piece? Whatever the true circumstances of the discovery of the Gibraltar 1

skull were, it is almost certain that we will never know.

References

Broca, P. (1869)

Remarques sur les ossements des cavernes de Gibraltar. In: Bulletins de la

Société d'anthropologie de Paris, II° Série. Tome 4. pp. 146-158;

Brown, A. (1867)

On the geology of Gibraltar, with especial reference to the recently explored

caves and bone breccia. Proceedings of the Royal Artillery Institution,

Woolwich 5: 295–304.

Busk, G. (1864a)

Pithecoid priscan Man from Gibraltar. The Reader (London) 4 (23 July): 109–110.

Busk, G. (1864b)

Ancient human cranium from Gibraltar. The Bath chronicle. Special daily edition

September 22 1864: p. 3.

Duckworth,

W. L. H. (1911). Cave exploration at Gibraltar in September, 1910. Journal of

the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland 41: 350–380.

Huxley T.

H. (1863). On Some Fossil Remains of Man, in

Evidence as to Man's place in nature. Williams & Norgate, London.

Murchison,

C (1868). Hugh Falconer, biographical sketch in Falconer Palaeontological Memoirs and Notes of the Late Hugh

Falconer, 1868.

London:

Spottiswoode and Co; 1868:xlix.

Mayer, F.

J. C. (1864a). Ueber die fossilen

Ueberreste eines menschlichen Schädels und Skeletes in einer Felsenhöhle des

Düssel- oder Neander-Thales. In: Archiv für Anatomie, Physiologie und

wissenschaftliche Medicin. (Müller's Archiv), Heft 1, 1864, S. 1–26.

Mayer, F.

J. C. (1864b). Zur Frage über das Alter und die Abstammung des

Menschengeschlechtes. In: Archiv für Anatomie, Physiologie und

wissenschaftliche Medicin. (Müller's Archiv), 1864, S. 696–728

Menez, A. (2018).

The Gibraltar Skull: early history, 1848–1868. Archives of natural history,

45(1), pp.92-110.

Pavid, K.

(2019). A new look at the Gibraltar Neanderthals. NHM at: https://www.nhm.ac.uk/discover/news/2019/july/a-new-look-at-the-gibraltar-neanderthals.html accessed 21/08/2021

Schrenk, F.

and Müller, S. (2010). Die Neandertaler C. H. Beck München.

Schwalbe, G. (1890). Studien iiber

Pithecanthropus erectus,” ‘Zeitschr. f. Morph, u. Anthropol.,’ v.1,

pp. 16-240.

Schwalbe,

G. (1901a). Der Neandertalschiidel,” ‘Bonner Jahrbiicher,’ part 106.

Schwalbe,

G. (1901b). Uber die specifischen Merkmale des Neandertalschadels,” ‘

Verhandlungen der anatom. Gesellsch.’ 15 Versammlung in Bonn, pp. 44-61.

Schwalbe,

G. (1904). Die Vorgesehichte des Menschen, Braunschweig.

Schwalbe,

G.A. (1906). Studien zur Vorgeschichte des Menschen (Vol. 1) p. 154 E. Nägele.

Sollas,

W.J., 1908. VII. On the cranial and facial characters of the neandertal race.

Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Containing

Papers of a Biological Character, 199(251-261), pp.281-339.

Turner, S. W. (1910). Letters to Sir Arthur Keith, Archive of the Royal College of Surgeons of England, London: Folder KL II MS0018/1/16/1–19. Now held at the Natural History Museum