Another paper on Art in the form of hand and foot prints came out recently. This time the location was most unexpected: the Tibetan Plateau at almost 4300 a.s.l., of all places. Studied and reported by Zhang et al. (2021). The site borders a geothermal hot-spring, at Chusang, which the lead author had investigated back in 2001.

A false colour image of travertine rock upon which the foot and hand prints are impressed from Zhang (2021) Fig. 2 Original caption reads: Colour rendered 3D model of the parietal art-panel. The individual track codes are indicated along with the approximate location and date of two samples extracted from the slab.

Zhang’s team at the Chusang site in 2018. Clockwise from the left: Zhang seated above the Art-panel with part of Boqionggang village visible in the background; the team examining the promontory where the Art-panel is situated; Zhang examining the slab of travertine and Art-panel All from Scott (2021).

Locations of investigation at the Chusang site from a map generated in Google MyMaps. Barden (2022).

The most stunning fact is that hand and footprints, when dated by the U-Th method turned out to range in date between 169 and 226 ka BP. This is an extraordinary finding, with the dates obtained making this the world’s oldest piece of art!

As such it is worth carefully examining how the dating was carried out. Zhang et al. state that (italics my own):

- Field sampling involved taking bulk samples using a hammer and chisel from which precise samples were subsequently drilled using a diamond tipped drill in the laboratory.

- Uranium series dating has been used in dating carbonate deposits successfully elsewhere in Tibet for dating thermogene travertine similar to those at Quesang

- The dense travertine layers at Quesang form with the thicknesses of between 200 and 2000 mm. The calcite crystals are inlaid closely with only a few pores and the dense laminated travertine has no, or little, recrystallization and few impurities. There is no evidence of bioturbation. Important because pores or impurities could affect the U/Th dating. Similarly Bioturbation could introduce materials which could also affect the dating.

- The measured δ234U and 230Th/238U activity ratios show that all dated travertine samples demonstrate closed-system behaviour. This is key, as a closed system would not allow uranium or thorium to enter or leave the system. Thus the results should be accurate and give a true age for date at which the travertine had the foot and hand prints impressed in it.

- (This was) confirmed further by our binocular observations on the U-Th dating samples.

- Impurity content is reflected in the 230Th/232Th ratio and a lower 230Th/232Th ratio indicates high levels of detrital 232Th impurity in the sample. Consequently, samples/dates with a 230Th/232Th ratio <20 × 10−6 were rejected from the age modelling. Again, a key point as excess thorium may be integrated into a sample through detrital material deposition in lake systems, or infiltration of uranium into bone samples after burial. Such sources of contamination can introduce significant age errors into sample measurements but can be predicted ahead of analysis.

- The dates were modelled using a kernel density estimate (KDE) distribution for all sampled units, including those that contained the tracks and from those located above and below the tracked horizon. KDE modelling is a hybrid Bayesian/frequentist approach that is used to estimate and graphically represent the underlying distributions of discrete data points. In this study, KDE modelling was done using the KDE_Model function in OxCal 4.4.2, which employs a Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) implementation to generate an equal number of random samples from each of the events specified within the kernel probability distribution. The calibration component of OxCal was disabled allowing older dates to be modelled. We used the default values in OxCal for both the kernel and bandwidth estimates to evaluate the age distribution. In addition, the start and end boundary ages were determined using the Boundary function in OxCal. While disabling the calibration component of OxCal 4.4.2, is necessary for the modelling of older dates, I am uncertain as to how this may affect the reliability of the ages generated for the travertine layers above and below the layer in which the foot and hand impressions were found

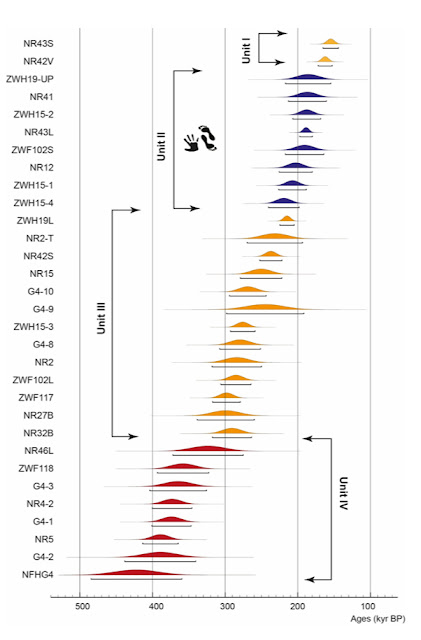

The authors produced a chronology of layers I-IV, with layer II being the one in which the foot and hand prints were found. It is worth noticing that layer I was missing from directly above layer II, thus exposing to the elements and human view. Zhang (2021), states that this block had been removed by natural processes of erosion. The team therefore sampled the immediately adjacent, remain travertine of layer I. Considering the congruent results shown by their chronology, this doesn’t seem to have proved problematical for the sequence of dates obtained. See chronology below:

Zhang (2021b) U/Th chronology. Original caption reads: Figure S11. U/Th dates organized by age and by units I to IV. Produced in OxCal v.4.4.2 r:5 [3]. It shows the age of unit II and the contained art-panel are part of a continuous depositional sequence.

Next the authors carried out an ichnological assessment of the hand and foot prints. Ichnology is the study of fossilized tracks, trails, burrows, borings, or other trace fossils as evidence of the occurrence or behaviour of the organisms that produced them. The authors used techniques recommended by international scientists as ‘best practice’. Part of this approach consisted of capturing 3D models of the prints for accurate analysis of their morphometrics. Below are diagrammatic representations of their results:

Zhang (2001a L and 2021b R) morphometric analysis of hand and foot prints. Original captions read: Fig. 3. Colour rendered 3D models of the parietal art-panels. (a) High resolution scan of the surface, note the plane has not been corrected to the orthogonal to minimise processing due to the size of this model… (b) Oblique image of the art-panel. (c, d) Close-up images of selected tracks. (e) Holocene tracks close to the current bathhouse at Quesang and interpreted here as an example of parietal art. Note the finger flute to the posterior of the handprint – arrowed. (L) and Fig. S6. Geometric morphometric comparison of the feet in the art-panel with reference materials. a. Distribution of landmarks following a Generalized Procrustes Analysis. Included populations are modern experimental tracks left in sand (N=356), plus fossil footprints from Namibia (N=78) and White Sands National Park (N=33). The 95% confidence ellipses are shown by the tan polygons. b. Thin-plate splines compare the mean landmark positions of the tracks in the art-panel with modern and fossil footprints. c. Principal Components Analysis of the landmark data with 95% confidence ellipses shown for each population. d. Length to width ratio for feet as defined in the UMTRI/CPSC [1] child with data from that source and the feet from the art-panel. (R).

Overall, the Zhang (2021a) results show that both hand and footprints group with modern humans, with some anomalies, such as particularly long fingers. Note that the Tibetan footprints group most strongly with the (presumably) modern human footprints from White Sands National Park in the USA. The American footprints have been carefully dated to around 22,000BP. They are, therefore, almost certainly from modern humans. However, these hominids must have entered the continent prior to the LGM and consequently, may show some archaic morphology in their hands and feet. Coincidentally, the sizes of the hand and footprints indicate that they were made by children of approximately 12 years of age, similarly to many of those studied by Fernández-Navarro, et al (2022) and covered in my last post (see Here).

The last subject that Zhang (2021a) considers is a favourite topic of mine, namely: “Are they art?”. Here are his arguments, verbatim (note I have inserted the years of the most pertinent references Zhang cites):

“Defining what is art depends on the definition one applies. Aristotle through the Greek concept mimesis (to mimic) provides us with a potential definition. Here art is a copy of something else. Much of what is defined as art fits this definition up until the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries when notable breaks occurred with the idea of imitative art. In the mimesis definition, the artist sees something and imitates it, notwithstanding any additional flourishes they might make. The Tibetan art-panel meets this basic criterion, but with its own flourishes. The placement of the prints is not as they would naturally occur, with tracks spaced by movement, or hands placed to stabilize; rather, the artist has taken a form that was already known through lived experience (i.e., the artist presumably having seen their own footprints), and took that form (the footprint) and reproduced it in a context and pattern in which it would not normally appear. This is made even clearer by the addition of the handprints, which are not commonly seen in lived experience. In the context of parietal art, Crowther (2007) states that art is not necessarily a revered object or image but items that form aesthetic configurations, whose style is original from the creator’s viewpoint and thereby creates a distinctive kind of aesthetic unity. It is a definition that has echoes in that provided by Davies [36] where excellence of skill no doubt derived from Kant is highlighted, along with traditions of a genre and the intention of the maker that it should be received as art. Lewis-Williams (2002), on the other hand, suggests that art was born of leisure with the simple aim of enjoyment, fun or decoration, the action of an idle or playful moment would fall under such a definition. Two children playing in the mud and intentionally creating a set of tessellated prints during an idle moment is what we probably have at Quesang and falls under most of the definitions of art outlined above. After all, most parents would describe their children’s tentative artistic endeavours as art and proudly display them. Moreover, the art-panel falls into the artistic tradition of creating art via hand stencils, which is accepted as common examples of parietal art (Brumm et al 2021). There is also an established tradition of children as Palaeolithic cave artists (Sharpe et al. 2006 and Bednarik 2008). We therefore conclude that the composition of hand and foot traces described here constitutes ‘‘art” under a range of definitions, although given the range of possible definitions some might disagree.”

These arguments actually, hold water for me and persuade me that the children who made them emplaced them did so in an evolving, playful sequence that ended with a composition that seems entirely intentional. Thus they do indeed constitute art, contra my previous post (see here)

Conclusions

1. The dating is almost certainly secure, with the small caveat noted above. However, Zhang’s work at the site in 2002 was challenged on a number, of fronts. For example Bednarik (2021) commented on Zhang (2021): “An international team recently discovered a few hand and foot impressions of juveniles in a hardened travertine deposit at the Quesang Hot Spring site in Tibet. They correctly proposed that the age of these prints should approximate the rock’s age, which must have been soft and still forming at the time they were produced. They secured U–Th ‘dates’ from the travertine that would place the age of the formation between 169 ka and 226 ka. On that basis, they claimed to have found the oldest known rock art globally. Due to the date and location they hypothesise that the Art panel was probably made by Denisovans.”

Bednarik (2021) states strong objections to the use of U/Th dating worldwide for dating rock art. He has concerns about the dating used in Spain to re-date rock art to older dates, an example being the attribution of certain geometric paintings at El Castillo cave. Similarly he believes that the technique, as applied to rock art from France, Indonesia and particularly China gives erroneous results that are (in some cases), orders of magnitude too old.

Bednarik lists possible causes of excessive age results:

- In reprecipitated carbonate deposits (such as travertine and speleothems) depletion of U by moisture may occur

- Solution may also remove detrital Th

- There may be a transformation of aragonite to calcite

- Samples may be contaminated by components of the support rock

- The significant variation of U concentrations in coeval calcite skins demonstrated to occur on a millimetre-scale that may be greater than 100%

2. The conclusion that the hand and foot prints were made (if the dates are correct) by Denisovans, is agreed upon by both Zhang (2021a) and Bednarik (2021). Indeed, on the face of it, as Denisovans seem to have been the only hominids on the Tibetan plateau in the interval 169 to 226 ka BP, children of this species must have made the hand and foot impressions, right? Due to the paucity of Denisovan skeletal remains we don’t actually know whether their foot and hand morphology was similar to modern humans or closer to Neanderthals, as is widely assumed.

While it seems overwhelmingly likely, that Denisovan children made them, there is of course another slight possibility: modern human children, actually did make them. Evidence comes in the form of a paper on the unequivocally, modern human teeth excavated at Fuyan Cave in Daoxian, southern China. These have been dated to between 80,000 and 120,000BP. Therefore there is a small chance that an early, modern human migration out of Africa were the individuals that made this art.

References

Barden, N. (2022). Denisovan distribution in Asia at: https://www.google.com/maps/d/edit?mid=1amcpq1o1z-hhTlJ88eVdGqq3eGU&usp=sharing

Bednarik, R.G. (2008) Children as Pleistocene artists. Rock Art Res 2008;25:173–82.

Bednarik, R.G. (2021) Direct Dating of Chinese Immovable Cultural Heritage. Quaternary 2021, 4(4), 42

Brumm A, Oktaviana AA, Burhan B, et al. (2021). Oldest cave art found in Sulawesi. Sci Adv 7: eabd4648.

Crowther P. (2007) Defining art, creating the cannon. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2007.

Fernández-Navarro, V., Camarós, E. and Garate, D., 2022. Visualizing childhood in Upper Palaeolithic societies: Experimental and archaeological approach to artists’ age estimation through cave art hand stencils. Journal of Archaeological Science, 140, p.105574.

de Guzman, C. (2021). Chinese Scientist Hopes to Conserve What May Be the World's Oldest Art. Time Magazine, at: https://time.com/6107313/oldest-prehistoric-art/ accessed 15/04/2022

Lewis-Williams, D.J. (2002). The mind in the cave: consciousness and the origins of art. London: Thames & Hudson.

Liu, W., Martinón-Torres, M., Cai, Y.J., Xing, S., Tong, H.W., Pei, S.W., Sier, M.J., Wu, X.H., Edwards, R.L., Cheng, H. and Li, Y.Y., (2015). The earliest unequivocally modern humans in southern China. Nature, 526(7575), pp.696-699.

Meyer, M.C., Aldenderfer, M.S., Wang, Z., Hoffmann, D.L., Dahl, J.A., Degering, D., Haas, W.R. and Schlütz, F., 2017. Permanent human occupation of the central Tibetan Plateau in the early Holocene. Science, 355(6320), pp.64-67.

Scott, M. (2021). How the World’s Oldest Artwork Was Uncovered in Tibet. Sixth Tone at: https://www.sixthtone.com/news/1008554/how-the-worlds-oldest-artwork-was-uncovered-in-tibet accessed 16/04/2022

Sharpe K, and L Van Gelder. (2006) Evidence for cave marking by Palaeolithic children. Antiquity 80: 937–47.

Zhang, D.D., Bennett, M.R., Cheng, H., Wang, L., Zhang, H., Reynolds, S.C., Zhang, S., Wang, X., Li, T., Urban, T. and Pei, Q., (2021a). Earliest parietal art: Hominin hand and foot traces from the middle Pleistocene of Tibet. Science Bulletin, 66(24), pp.2506-2515.

No comments:

Post a Comment