In August 1856, quarrymen working on the limestone cliffs of the Neander Thal, that is the Neander Valley, climbed into a small cave. It was filled with mud which needed removing. The quarry owners were herren Beckershoff and Pieper both members of the regional membership in the Natural Science Association, who had a keen interest in bear and mammoth bones, occasionally found in cave clay. Thus it was that Herr Beckershoff was present that day. On seeing some of the fossils, work was halted and Beckerschoff ordered his men to collect them and then to search the sediment outside for any other bones that had been inadvertently thrown away, and keep them in strict safekeeping. Eventually the men assembled 16, which consisted of a skullcap, two femora, the three right arm bones, two of the left arm bones, ilium, and fragments of a scapula and ribs. The owners kept the bones as curiosities until Pieper realised they might be of interest to an acquaintance of his.

The original set of bones discovered in 1856. Photo credit: Neanderthal Museum/S. Pietrek.

The Neander Thal. Original caption reads: Three hikers looking at the Neander Cave. This drawing by the Rotterdam artist Gerardus Johannes Verburgh, 1803, is the oldest known depiction of the Neander Valley with the Neander Cave. The hikers are facing west, looking downstream along the Düssel River. They are standing on top of the 'Engelskammer' or 'Rabenstein' rock formation on the right of the Düssel. The Feldhof Cave was situated on the opposite side. Photo credit : Don Hitchcock picture and text from the Neanderthal Museum, Mettmann, near Düsseldorf, Germany (19).

The cave was situated in a limestone gorge with the interior dimensions of 3m in width by 5m in length by 3m in height, and a 1m opening, 20 m above the valley floor in the south wall which was 50m high. The cave got its name from the nearby large farm of the Feldhof. The bones belong to at least three distinct individuals.

That autumn Pieper passed the bones on to the locally well regarded teacher and naturalist, Johann Carl Fuhlrott. At the time, Fuhlrott was primarily interested in botany, and thus did not immediately rush to the cave to see if there were further specimens to be discovered. It was only after beginning to research these strange bones that he turned his attention to palaeontology.

Johann Carl Fuhlrott (1803-1877) was the first naturalist to recognise Neanderthal remains, importantly he stated, that he believed them to be from an antediluvian form of man. Photo credit: ref. 20.

It is a matter of conjecture how a local newspaper became aware of the find, or Fuhlrott’s opinion of the bones, but without his permission, a story was published by the Elberfeld newspaper and the Barmer local Journal, on September the 9th 1856:

“In neighbouring Neanderthal, a surprising discovery was made in recent days. The removal of the limestone rocks, which certainly is a dreadful deed from a picturesque point of view, revealed a cave, which had been filled with mud-clay over the centuries. While clearing away this clay a human skeleton was found, which undoubtedly would have been left unconsidered and lost if not, thankfully, Dr. Fuhlrott of Elberfeld had secured and examined the find. Examination of the skeleton, namely the skull, revealed the individual belonged to the tribe of the Flat Heads, which still live in the American West and of which several skulls have been found in recent years on the upper Danube in Sigmaringen. Maybe the find can help to settle the issue of whether the skeleton belonged to an early central European original inhabitant people or simply to one of Attila's roaming horde's men.”

This news reached the university in Bonn and two professors of anatomy, Hermann Schaaffhausen and August Franz Josef Karl Mayer. They requested that Fulrott send the bones for their examination. Fuhlrott, however, demurred and stalled as it was a simple fact that he was intensely interested in the bones and was examining and researching, their possible origin himself. He had good reason for this as he states in his 1859 paper (1): “I may remark that I recognized the bones as human at first sight and of the importance of the find, even if not in its present extent, was not in doubt for a moment.”

Eventually he relented and took the bones to Bonn himself. Unfortunately, Mayer was ill and bedridden at the time and it was Schaaffhausen alone (or possibly with one other) who examined them. Fuhlrott (1), records his reaction: “It must have given me great satisfaction that both experts devoted the most lively attention to the subject of my study, and, surprised by its partial novelty, concurred with the views which I had formed as to the probable origin and scientific importance of the find.”

Tattersall (3), summarises Schaaffhausen’s paper succinctly: “Schaaffhausen described the unusually massive bone structure of the find in detail and particularly noted the shape of the cranium - especially the low, sloping forehead and the bony ridges above the eyes. He considered these characteristics to be natural, rather than the results of illness or some pathology (abnormal development). They reminded him of the Great Apes. Nevertheless, this was not an ape, and if its features were not pathological, they must be attributed to the age of the find. Although his own search for specimens that were similar to the Neanderthal was unsuccessful, he came to the conclusion that the bones belonged to a representative of a native tribe who had inhabited Germany before the arrival of the ancestors of modern humans.” Schaaffhausen also included, a plate of the cranium with the Plauer skull for comparison which, I present below:

Plates 1-6 from Schaaffhausen (2). I find this illustration most pleasing as it shows the differences between a Neanderthal skull (Figs. 1-3) and a modern human (Figs. 4-6), very clearly. The obvious differences must have given all but determinedly, closed-minded sceptics pause for thought.

With reference to Schaaffhausen’s

own words (2) they give a slightly different emphasis to what he believed about

the Neantherthal specimen: “I followed this.. with a brief account of the

anatomical examination of the bones which I had carried out, as the result of

which I made the assertion that the striking shape of this skull was to be

regarded as a natural formation which had hitherto not been known, even in the

roughest races, that these remarkable human remains belonged to a higher

antiquity than the time of the Celts and Germans, perhaps descended from one of

those savage tribes of north-western Europe of which Roman writers report, and

which the Indo-European immigration found autochthonous, and that it is

possible that these human bones came from a time when the last vanished animals

of the Diluvium also still lived, could not be disputed, there was no proof for

this assumption, i.e. for the so-called fossility of the bones, in the

circumstances of the discovery.”

This slightly ‘faint praise’ praise for Fulhrott’s view of the antiquity of the bones, may have been what spurred him on to publish a detailed assessment of the remains himself (1). Fulhrott gives a detailed account of the discovery of the bones and based on his interview with the workers who unearthed them, and asserts that a full body must have originally been in the cave in anatomical position. He describes the unusual characteristics of the cranium, and illustrates it.

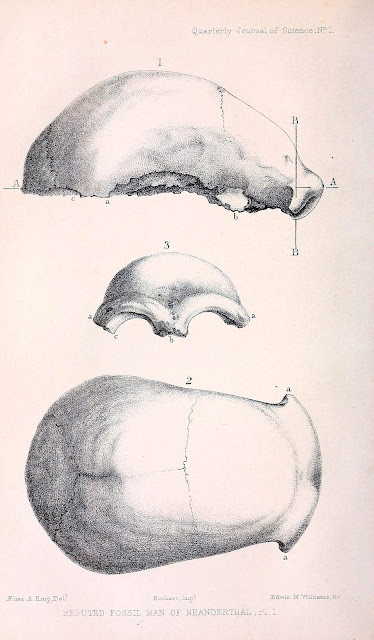

The Neanderthal cranium, as illustrated by Fuhlrott (1). Notice that Figs. 1 and 3 are similar to Schaaffhausen’s plate, but that the partially rotated Fig. 2 is completely original and emphasises the strongly formed brow ridges.

Fuhlrott goes on to explore how the Neanderthal skeleton got into the cave from through crevices from above or through the cave mouth. He entirely concentrates on water action as the only possible source of the bones ending up in the cave, and ignores the possibility that the individual entered the cave himself and expired there, or was placed there by his community. He goes on to cite other occurrences of fossil bones of great antiquity, such as those of mammoths found in an identical clay/mud matrix in the same regional geological formation. While these are possibilities, it is unlikely, given the original position of the body, that transport by water was the mechanism by which it arrived at the find spot. Unless it was a recently dead, whole corpse of course.

Lastly Fuhlrott discusses the surface dendritic crystal formations observed on the bones. He sets great store in these deposits of manganese and iron, claiming that they indicate that the bones are of great age. While I have no knowledge of the rate of formation of these deposits, Fulhrott’s assertions do not seem, entirely convincing. This was also the view of anatomists of the time such as Mayer and Schaafhausen, himself.

Overall German naturalists were not convinced that the fossils were significant. More importantly, they were not convinced that the fossils were even old. Fulhrott a pugnacious man, felt ignored and even slighted by his countrymen and decided to see if the foremost geologist of the age, Charles Lyell could date the cave sediments and thus go some way towards proving the age of the Neanderthal bones. Therefore, Fulhrott determined to invite Lyell to Germany.

The following aspect of the story is adapted from Madison (5) and Ashworth (4): Lyell responded to the invitation by Fuhlrott and travelled to Germany in 1860. His goal was to examine the cave and determine the sediments in which the fossils were found (and therefore the age of the fossils). The fossils’ antiquity was important to nineteenth century naturalists because it could help determine whether the bones were indeed old and fossilized, rather than some recent human who died in a cave. Because they had no way to directly date the fossils, an examination of the cave sediments could help resolve the issue.

Fuhlrott gave Lyell a tour of the cave, showed him the fossils, and even gave him a cast of the skull. Lyell ultimately determined that the Neander fossils were likely very old. He made this claim based on the cave sediments as well as my personal favourite nineteenth century geologist trick: the tongue test. Lyell stuck the fossils to his tongue, concluding that they had indeed gone through the fossilization process. At the time, bones were considered fossilized if they had lost enough of their “animal matter” that they “adhere[d] strongly to the tongue.

Lyell returned to London and gave the cast of the skull to anatomist Thomas H. Huxley. Huxley, along with his good friend George Busk, studied the cast of the fossil over the next couple of years. After retiring from the Navy Busk, indulged himself in his passion, that of studying marine invertebrates, especially Bryozoa. Initially, he had thought to publish some of his researches on the subject in a self-published journal. However, with the cast of the Neaderthal to hand and the many illustrations he had obsessively drawn of it, he decided to publish a translation of Hermann Schaafhausen’s paper, substituting the original plates with illustrations he had made. Thus it was that his Natural History Review, included both the translated paper and his own drawings in its first volume in 1861. This paper basically introduced Neanderthal man to the English audience, both lay and professional.

George Busk created numerous illustrations which were subsequently used in Huxley’s Evidence as to Man’s Place in Nature (1863) and Lyell’s Geological Evidences of the Antiquity of Man (1863)

Busk’s plate from Huxley’s Evidence as to Man’s Place in Nature (1863). The brow ridge is so clear in this illustration, and so different from anatomically modern humans, that arguments that it was not a different species from us, now seem absurd. Phot credit ref 6.

In Lyell’s book Geological Evidences of the Antiquity of Man 917), he gave a sketch of the Kleine Feldhofer Grotte and gave the opinion, that sediments therein were most probably deposited via the fissure which entered the cave from above. Whatever their route of ingress, they were most certainly ancient, not recent, in Lyell’s estimation.

Lyell’s sketch of the Klein Feldhoffer Grotte, made on site 1860. From ref 17.

The papers, books and illustrations lending support to the theory that the Neanderthal bones belong to an ancient form of man but in no way suggesting its age, except that it was ancient, caused deep disquiet in the German intelligencia, especially to the renowned pathologist and cell biologist Rudolph Virchow. Unable to take on the project himself, Virchow asked Josef Mayer to ‘take another look’ at the bones. Implicitly, this request seems to have been, for the purpose of refuting the English views of the Neanderthal finds. The published results of Mayer’s examination, pleased Virchow greatly.

Mayer’s paper (7), carefully recorded the proportions of the cranium and other bones and their unusual features and found against their being anything other than pathological in every case. He also considered them relatively recent. I have been unable to find Mayer’s paper (7), except within a critique of them written by Huxley (8).

I won’t go through Huxley’s renunciation of Mayer’s paper in detail, Huxley has done a fine job of demolishing Mayer’s argument as to the recent and non-fossil origin of the Neanderthal fossils. Huxley, in fact called parts of it frivolous! If we look at Huxley’s conclusion we find it encapsulates his feelings about Mayer’s paper.

Huxley (8), says: “And now, having fairly got the man into the cave and covered him up by the 'rebounding' of cataracts of muddy water, who was he?

A 'Mongolian Cossack' of Tchernitcheff's corps d'armée is Professor Mayer's suggestion;–based upon three reasons: the first (p. 20) that the thigh bones are curved like those of people who spend their lives on horseback; the second (p. 21), that any guess is better than the admission that the skeleton may possibly be thousands of years old; the third, (p. 21-2) that, after all, the skull is more like that of a Mongol than that of an ape, or a Gorilla, or a New Zealander.

Thus the hypothesis which is held up to us by Professor Mayer as an example of scientific sobriety comes to this: that the Neanderthal man was nothing but a rickety, bow-legged, frowning, Cossack, who, having carefully divested himself of his arms, accoutrements, and clothes (no traces of which were found), crept into a cave to die, and has been covered up with loam two feet thick by the 'rebound' of the muddy cataracts which (hypothetically), have rushed over the mouth of his cave.

Professor Mayer must, indeed, have a firm belief that anything is better than admitting the antiquity of the Neanderthal skull!”

What the eventual result of this disputation might have been, we will never know, for at this point another scientist entered the fray: William King. King was an Anglo-Irish geologist at Queen's College Galway. How he became involved in the matter of the Neanderthal specimen is unknown. However, in 1863 he attended the 33rd meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of science, and presented his views, concerning a cast of the cranium (9). At the end of the paper it is mentioned by the unknown commentator that due to these observations, he concluded that the Neanderthal specimen was not of the same species as man, and named it Homo neanderthalensis.

Unexpectedly this brief lecture was well received, and he was encouraged to write a detailed paper explaining the anatomical differences that separated the Neanderthal from man. The paper (10), came out in 1864. It concentrated on comparing the measurements of the fossil skull and how the various parts relate to one another, with that of a modern man. This approach was extremely lucid and highlighted, the many differences other previous workers had noted, but failed to give sufficient weight to. Below I give a few examples:

Frontal: Frontal sinuses, it is well known, do not always coexist with prominent brow ridges, as for example in the Australian and the Chimpanzee: on the other hand, the former may exist without being associated with any more than an ordinary development of he latter.. But whether the Neanderthal sinuses extend the whole length of the brow-ridges, or they are simply confined to the region of the glabella, their large size, in either case, is unusual in man, and they strongly approach to, or resemble, as the case may be, those of the Gorilla.

Orbital cavities: The orbital cavities appear to have had a circular rim, as in certain apes, there being no angle in that part joining the glabella. This is a feature unknown in any of the human races: in them the orbits are always subquadrate.

Temporals: As already stated, only the impression of the upper squamosal is seen on the parietals; but it suffices to show, as pointed out by Huxley, that this part had a comparatively low arcuation: the highest point of the arch reaches little more than half the height it attains in ordinary human skulls. Besides occurring among apes, an equally low arcuated squamosal distinguishes the human foetus; and in some savage races – Australians and Africans – the same part is also depressed, but not so much as in this fossil.

Occipital: The upper portion of this bone is quite semi-circular in outline, its sutural (lambdoidal) border running with an even crescentic curve from one transverse ridge to the other:* generally in human skulls.. the outline approaches more or less to an isosceles triangle.† The width of the occipital at the transverse ridges is much less than is common in man; and the disparity is the more striking in consequence of the widest portion of the fossil occupying an unusually backward position. Taking into consideration the forward and upward curving of the upper portion of the occipital bone as previously noticed, its semi-circular outline, and smallness of width, we have in these characters, taken together, a totality as yet unobserved in any human skull belonging to either extinct or existing races..

Parietals: - In man the upper border of these bones is longer than the inferior one; but it is quite the reverse in the Neanderthal skull. The difference, amounting to nearly an inch, will be readily seen by referring to Figures 1 and 2, in Plate II., the former representing the right parietal of a British human skull, and the latter the corresponding bone of the fossil. These figures also show that the Neanderthal parietals are strongly distinguished by their shape, and the form of their margins: in shape they are five-sided and not subquadrate, like those of the British skull; while their anterior and posterior margins have each exactly the reverse form characteristic of Man.

* Plate II Fig. 4

† Plate II Fig. 3

King Plate 1. Side, front and top views of the Neanderthal from the Feldhoffer Grotte.

King Plate 2. 1: Parietal of the Neanderthal; 2: Parietal of modern human; 3: Occipital of modern human; 4: Occipital of the Neanderthal and 5: Side view of the skull of a modern human. Photo credits: both ref 10.

There the matter should have rested. The vast majority, of English, incipient ‘palaeontologists’ believed the remains to belong to a new human species: Homo Neanderthalensis.

Unfortunately, Rudolf Virchow the eminent German pathologist, vigorously opposed the view that the Neanderthal skeleton was a primitive precursor of Homo sapiens (11). After studying casts of the inner and outer surfaces of the cranium for several years he was finally able to examine all the bones at Elberfield, in 1872. Consequently, the same year, he presented the results of his examination of the Neanderthal bones, at a meeting of the Berliner anthropoligische Geselleschaft (13). He declared the Neanderthal man to be a pathological specimen, perhaps of relatively recent origin, a view he maintained to the end of his life.

Virchow explained various characteristic of the skull as due to senile atrophy, hyperostosis possibly associated with senile changes, premature synostosis and traumatism. Futhermore, from his examination of the other bones found with the skull, Virchow decided that the Neanderthal man had suffered from arthritis deformans due to aging and to the moist, cold environment of the caves in which he lived. Finally, the extensive curvature of the upper and lower extremities led Virchow to diagnose this phenomenon as rachitic in origin (12). These views were repeated in 1873 before the German Anthropological Society and again on January 7th 1875 in a memoir on the cranial characteristics of the lower races presented to the Royal Academy of Sciences.

Virchow’s views profoundly affected the final 20 years of Fulrhrott’s life: abroad, particularly in England and to a lesser extent in the rest of Europe he was well respected. In his homeland, however, his views on the Neanderthal skeleton were never taken seriously and he was often derided. He died in 1877, still unrecognised as a pioneer of palaeontology in his homeland.

The cave was completely, destroyed during the 19th century as a result of industrial-scale limestone quarrying which widened the gorge. The location of the cave was soon forgotten and by 1900, unknown.

From 1991 on the Neanderthal bones were re-analyzed by an international team of researchers. Radiocarbon dating yielded an age of 39,900 ± 620 years (15), which suggests these individuals belonged to the last populations of this human species in Europe.

In 1997 the research team succeeded in extracting mitochondrial DNA from the humerus of the type specimen (16), the first sample of a Neanderthal mtDNA ever extracted. This evidence led to the conclusion that Neanderthals were genetically distinct from anatomically modern humans.

Also in 1997 excavations in the Neander Valley determined and reconstructed the exact location of the former "Little Feldhof Grotto". Underneath layers of residue, loam fillings and blasting rubble of the limestone quarry, a number of stone tools and a total of 24 Neanderthal bone fragments were discovered. No stone tools had been unearthed from the cave previously. In 2000 the excavations continued and a further 40 human teeth and bone fragments were discovered, including a piece of the temporal and the zygomatic bone, which exactly fitted into the Neanderthal 1 skull. Another bone fragment, a condyle, could be associated precisely to the left femur.

Particular attention, was given to the discovery of a third humerus: two humeri were already known since 1856. The third humerus represents the remains of a second, more delicately built individual (perhaps a female?); at least three other bone fragments are also present twice. Called Neanderthal 2, the find was dated at 39,240 ± 670 years old, exactly as old as Neanderthal 1, within the margins of error. Moreover, a milk tooth was recovered and attributed to an adolescent Neanderthal. Based on the state of abrasions and the partly dissolved dental roots it was concluded, that it belonged to an 11–14 years old juvenile.

I’ll give the last word to specimen himself. 40,000 years ago he died in Klein Feldhoffer Grotte. From the, additional bones collected nearly 150 years later, it seems highly possible he was with his family at the time of his death. Did they die of cold or hunger? Were they swept to their deaths in a river torrent and their bodies deposited through a swallet-hole into the mud-filled cave? What their thoughts were, are unknowable, but it must’ve been an horrific end, whatever the case. I bring up these points, not to add a bit of human drama to this post, but just to say that these were people just like us, with hopes and dreams. And they deserve more respect than being reduced to mere objects.

The Neanderthal 1 cranium, photographed by George Busk, from ref. 18. Original caption reads: “Figure 1. A photograph of the Neanderthal cranium, viewed from above. Huxley Papers, Imperial College London, 1863, Volume 105, Box no 105, Series 19.

References

(1). Fuhlrott, C., (1859). Menschliche Ueberreste aus einen Felsengrotte des Dusselthals. Ein Beitrag zur über die Existenz fossiler Menschen. Verhandlungen des Nationales Verein des Preusisches Rheinlandisches und Westfalens, 16.

(2). Schaaffhausen, H. (1858): Zur Kenntniss der ältesten Rassenschädel. In: Archiv für Anatomie, Physiologie und wissenschaftliche Medicin. 1858, S. 453–478

(3). Tattersall, I., (1999). Neandertaler: der Streit um unsere Ahnen. Springer-Verlag

(4). Ashworth, W. B. (2021). Scientist of the Day - George Busk. At: https://www.lindahall.org/about/news/scientist-of-the-day/george-busk accessed 31/07/2022

(5). Madison, P. (2015). Charles Lyell & the First Neanderthal. At: https://fossilhistory.wordpress.com/2015/02/19/lyell-the-first-neanderthal/ accessed 31/07/2022

(6). Ashworth, W. B. (n.d). Primates in the Family, 1863. 17. Huxley, Thomas Henry (1825-1895). At: https://bladeandbone.lindahall.org/17.shtml accessed 01/08/2022

(7). Mayer, F., 1864. Über die fossilen Überreste eines Menschlichen Schädels und Skeletes in einer Felsenhohle des Düssel-oder Neanderthales. Arch Anat Physiol wiss Med, 1, p.26.

(8). Huxley, T.H., (1864). Further remarks upon the human remains from the Neanderthal. Natural History Review. Scientific Memoirs II. Williams and Norgate, London.

(9). William King: On the Neanderthal Skull, or Reasons for believing it to belong to the Clydian Period and to a species different from that represented by Man. In: British Association for the Advancement of Science, Notices and Abstracts for 1863, Part II. London, 1864, S. 81 f

(10). William King: The Reputed Fossil Man of the Neanderthal. Quarterly Journal of Science. Band 1, 1864, S. 88–97, hier: S. 96.

(11). ROSEN, G., (1977). Rudolf Virchow and Neanderthal man. The American Journal of Surgical Pathology, 1(2), pp.183-188.

(12). Virchow, R. (1872). Untersuchung des Neanderthal-Schadels. Z Ethnologie 4: 157-165.

(13). Virchow, R. (1873). In: Bericht uber die vierte allgemeine. Versammlung der deutschen anthropologischen Gesellschaft. Archiv Anthropol 6: 49

(14). Virchow, R. (1875). Ueber einige Merkmale niederer Menschenrassen am Schadel. Berlin, F. Dummeler, p7.

(15). Schmitz, R.W., Serre, D., Bonani, G., Feine, S., Hillgruber, F., Krainitzki, H., Pääbo, S. and Smith, F.H., 2002. The Neandertal type site revisited: interdisciplinary investigations of skeletal remains from the Neander Valley, Germany. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 99(20), pp.13342-13347.

(16). Krings, M., Stone, A., Schmitz, R.W., Krainitzki, H., Stoneking, M. and Pääbo, S., 1997. Neandertal DNA sequences and the origin of modern humans. cell, 90(1), pp.19-30.

(17). Lyell, C., 1863. The geological evidences of the antiquity of man: with remarks on theories of the origin of species by variation. J. Murray, London.

(18). Madison, P. (2016). The most brutal of human skulls: Measuring and knowing the first Neanderthal. The British Journal for the History of Science, 49(3), pp.411-432.

(19). Hitchcock, D. (2015). The original Neanderthal skeleton from the Neander Valley. From Don’s Maps at: https://donsmaps.com/neanderthaloriginal.html accessed 29/07/2022

(20). Less, G. C. (2017). Johann Carl Fuhlrott Naturforscher (1803-1877) At: https://www.rheinische-geschichte.lvr.de/Persoenlichkeiten/johann-carl-fuhlrott/DE-2086/lido/57c6c1fb1472d8.75713051 accessed 29/07/2022

Other Sources

Wikipedia (2022). At: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kleine_Feldhofer_Grotte accessed 29/07/2022

Wikipedia (2021). At: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Neanderthal_1#cite_note-23 accessed 29/07/2022

No comments:

Post a Comment