The settlement of Ulalinka or Улалинка, in Russian (co-ordinates 51°57'20.0"N 85°58'18.6"E) was

discovered in 1961 by Okladnikov, it lies partly under the old city cemetery on

the south-eastern outskirts of Gorno-Altaisk.

The first, source I could find regarding the manner of his discovery was Anatolevna

(2013). She quotes the author himself: “In his book "The High Hill" Okladnikov wrote: "In 1961, during the

local lore conference, the instinct of a hunter for primitive man led me and

ethnographer Tashchakov to this hill, forced me to cross a small mountain river

Ulalinka and climb up a steep hillside strewn with stones."”

Reading between the lines, I think we can conclude that local people

directed him to the site and upon inspection he found stone tools eroded out of

the slope.

This, is more or less, confirmed by a second source, Gavrilov (2012), who gives a little more detail about

the site’s discovery: “In 1961, the

famous Soviet archaeologist and historian AI Okladnikov came to Gorno-Altaisk

for several days. In his spare time, after a long-established habit, the

scientist began to search for new monuments of antiquity in the vicinity of the

city. His attention was drawn to the left bank of the Ulalinka River near

the old city cemetery. Here the river washed away a high terrace, in the upper

layers of which, before 1961, a parking lot was found for people who lived in

the late Paleolithic era (the end of the Stone Age).

At the bottom of the terrace

L.P. Okladnikov found several yellow-hazel, quartz with traces of rough

treatment by their man. It was these findings that struck him with his

closeness in the processing technique to the pebble tools of the Punjab (India)

and distant Africa, i.e. the oldest known tools of man's labour, which preceded

the tame chisels of the lower (early) Palaeolithic.”

However, when Okladnikov reported his finds and suggested great age for

them his colleagues were sceptical. They pointed out that two questions needed

answering about the site, before the tools could be accepted as truly ancient.

These were:

1.Do the pebble tools belong to the lower, ancient layers of the terrace

or have they been transported there, perhaps by water?

2. If so, then what is the age of these layers?

Therefore, a full excavation was required. This had to wait for eight

long years before it could be organised. Garilov (ibid.) continues:

“In June 1969 a group of

researchers from the Institute of the Institute of Physics and Technology of

the Siberian Branch of the USSR Academy of Sciences, headed by AP Okladnikov

(including the associate professor of the history department of the Barnaul

Pedagogical Institute, Umansky Aleksey Pavlovich, and the student-historian BGPI V.

Mamaykin) laid an exploratory dig on the slope terraces. During

excavations, in addition to a series of stone tools of labor, bones of some

fossil animals were found, in particular a tusk of an elephant or a mammoth.

In July of the same year,

students-historians BGPI on behalf of AP Okladnikov made a step-by-step

cleansing of the slope of the terrace. These were the first excavations in

the Ulalinsky parking lot.

During the excavation in 1969,

more than 500 pebble tools were found, as well as bones of small rodents.

Part of the slope was cleared

from the base to the top so that geologists could make a complete picture of

the structure of the terrace and, consequently, solve the question of its

origin and the age of the layer in which primitive tools of labour were

discovered.

I must say that before the

excavations in 1969, geologists were also not unanimous in explaining the

origin of the terrace and differently dated the time of its

formation. Thanks to excavations in 1969, the structure of the terrace was

traced on a wide front.

After studying it in the autumn of 1969,

geologists - Corresponding Member of the USSR Academy of Sciences VN Saks and

candidate of geological sciences S. L. Troitsky came to the conclusion that the

terrace (120-100 thousand years ago) was very old. This time was also

dated the layer containing pebble tools.

But the excavations of 1969 did

not give a clear answer to the question of how these weapons fell into the

ancient layer: whether they were left by the people who lived then (and,

therefore, are very ancient) or in fact, slid from the upper layer to the lower

one (and then belong to later time). This problem could only be solved after

excavation at the top of the terrace.”

Okladnikov (1982), states that he opened a pit on top of the terrace and

dug down over 5m. Garilov (ibid.) concludes:

“In the summer of 1970

excavations at Ulalinka were continued. In the lower part of the cover

layer, that is, at a depth of two meters [note the depth discrepancy with Okladnikov’s paper], dozens of the oldest pebble tools were found on the entire area of

the site. They proved that there is no question of any sliding of the

found tools from the upper layer, that they really, belonged to the lower

layer, that is, their grey antiquity was proved. This was confirmed by

archaeological materials, from which the tools of labour were made, and the

technique of production, and their types.”

Ulalinka excavation in 1969, from the Assa at the Megalithic Portal

(2016)

Okladnikov at Ulalinka in 1979, the year before his death. Original

caption reads: The excavation site; journalist B. Alushkin, academician

A. Okladnikov (center) and geologist V. Mylnikov at Ulalinsky parking lot

(1979). Source: Badanova (2015).

Anatolevna (ibid.), a local resident of Gorno-Altaisk, describes the site

as it is today:

“The site was named after the Ulala River. It is located near the

old cemetery on the left bank of the taiga river Ulala”.. “Poplar planting in

the old cemetery serves as fencing around the site. Garages, sheds,

residential buildings are built under the very precipice.”

Of the finds made by Okladnikov she states “more than 600 samples of

primitive tools from quartz were extracted.”

According to the ООПТ

России (Protected Areas of Russia) website (2018) the site’s importance was

first recognised by a decision of the Altai Territory Council of People's

Deputies in 1978 in a document entitled "On the Approval of Natural

Monuments of the Gorno-Altai Autonomous Region". In 1996 it received

national recognition as an ‘object of

historical and cultural heritage of all-Russian significance’, by presidential

decree. The site, however, was

largely ignored and left unprotected until 2012. Then, the Altai Republic,

prosecutor's office stepped in. It was reported, by Federal Press (2012) that

they demanded that the federal agency for managing state property and the

Ministry of Culture take measures to preserve the cultural heritage site,

Ulalinsky.

According to, Badanova (2015), action seems to have been taken: the site

now has a sign-board, and improvised

open-air museum based in a yurt, which also serves as a ticket booth. A museum complex is also planned.

Recent images of Ulalinka:

Ulalinka site from the south, showing the creeping development

threatening the site. Source: Wikipedia commons (2016).

New sign board at Ulalinka.

Source Badanova (2015)

Ulalinka site plan from the

Protected Areas of Russia, Natural Monument Passport. PDF download from ООПТ России (Protected Areas of Russia)

website (2018). Original caption reads: Fig 1 Site plan of the Ulalinka Natural

Monument.

View of Ulalinka from the

north(?). Source: Assa at the Megalithic

Portal (2016).

The only published paper on it is

that by its excavators A.P. Okladnikov, A.P. and G.A Pospelova (1982).

In their own words:

“The Ulalinka site, discovered in 1961, is located on the right

tributary of the Maima River, on the left bank of the Ulalinka below the

cemetery of Gorno-Altaisk. The site is situated in the submeridional fault

[meaning a fault in an almost north-south direction]. Zone separating the

Biisk-Katun and Kiam synclinoria. It is located on the edge of Iolgo Range,

which is composed of flint limestones, quartzites and other rocks of late

Proterozoic age [ended 542Mya]. These rocks are occur at a depth of 12m below

the Ulalinka River level and are overlain by Neogene and Pliocene-Quaternary

sediments.”

In this section, the authors are

trying to put the cultural levels in context to show what age they are.

“The Ulalinka section, in which two distinct cultural levels were

found, was exposed on the slope of the and in a pit dug into the hilltop to a

depth of 5.8m. The section’s strata differ in genesis and form three informal

units”

“In one of the pit’s walls the section was as follows: (1) modern,

black, soil 0.70m; (2) greyish-brown loam with worm tunnels and roots of

vegetation, 0.3m; (3) loessy light-grey loam with columnar parting and lime nodules,

0.3m and (4) loessy light-brown loam with lime nodules 0.4m. These four layers

comprise a loam unit of typical late-Quarternary appearance, an identification

confirmed by finds of molluscs. The first cultural level is confined to the

lower part of this loam unit. The section proceeds with (5) lumpy brown clay,

0.45m; (6) compact brown clay with iron hydrates, 0.5m; and (7) yellowish-brown

clay with some crushed stone, 0.45m. These layers comprise a middle clay unit

of which the general appearance indicates a much earlier Quarternary age than

that of the loam unit. Finally, the section includes (8) a boulder-pebble

horizon with gravel, crushed stone, unsorted fragments, flint limestones, porphyrites

and diabases associated or stained with yellow-brown ochre clay, 0.6m; (9)

yellow-brown ochre compact clay with rhythmically alternating thin inclusions

of white clay, 0.35m; (10) bright-yellow clay, 0.25m; and (11) crushed stone and

pebbles of quartzite and limestones, 1.5m. Layer 8 is the second main cultural

level of the section. These four layers comprise the lower clayey unit, the

rocks of which are typical of the Pliocene Altai foothills in their lithology

and multi-coloured character. Until this discovery, Palaeolithic artifacts had

not been found in Siberia under the thick cover of loessy loams in rough

sediments with pebbles and crushed stone. The upper cultural level is a typical

assemblage of Upper Palaeolithic implements, including a few flakes, some

fragments of prismatic core, a point, and a small scraper with semi-lunar blade

made of obsidian. These tools and many others from similar sites can be

attributed an age younger than the Sartan glaciation (less than 25,000 years).”

“The main cultural level of the section, associated with the boulder-pebble

horizon, differs from the upper one and from all other known Palaeolithic sites

in Siberia principally in the strikingly archaic shapes of the tools and their

primitive technology. The tools were made almost entirely from pebbles of

yellowish-white quartzite, whole or split in half, and sometimes from pebbles

of obsidian and quartzite fragments. The finds include choppers, chopping

tools, scrapers, a peculiar pebble core and tools with a spoutlike curved

projection that might have served as cutting instruments. All these tools are

nearly untreated pebbles, only slightly retouched (fig 1). All the artifacts

are amorphous. They may sometimes have served as cutting tools, sometimes as

scrapers, sometimes both functions at once. Their primitive diversity seems to

reflect the pursuit of a useful and stable shape. The stone inventory and the

techniques of manufacture are so primitive and peculiar that they cannot be

classified in the framework of the classic Lower Palaeolithic typology. The

nomenclature of the Western European schemes cannot be applied to them.”

A closer look at the

stone tools

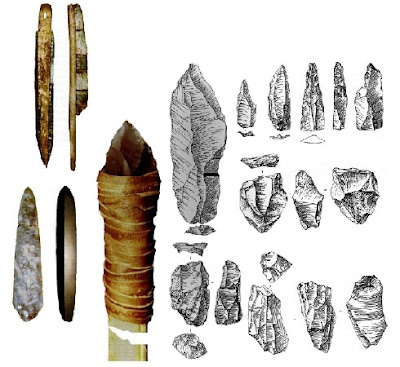

In their paper Okladnikov and Pospelova (1982) sparsely

illustrate their collected lithics:

Ulalinka primitive stone tools from Okladnikov and Pospelova

(1982). Original caption reads: Fig.1. Stone inventory Ulalinka, lower horizon.

1, pebble with marks of percussion

along the longitudinal edge; 2, tool

with re-touched projections; 3,

pebble chopping tool; 4 scraper-like

tool; 5, pebble core.

Ulalinka lithics from Russia’s Archaeological Web Museum

(1999). Original caption reads:

According to the latest archaeological finds, ancestors of

present man lived in Gorny Altai many hundred thousand years ago. Ulalinka

which lies within the limits of today's Gorno-Altaisk, is the most ancient

settlement of primitive man. During the excavation of the Ulalinka site some

primitive stone tools were found. The fire technique, that is the heating and

quick cooling of stones, was used when making the tools. Ulalinka's finds are dated

within the limits of the lower Palaeolithic period - from 150000 BC to 1.5

million years.

Stone tools, purportedly, from Ulalinka from Anatolevna (2013).

No source is given and no caption. Provenance unknown. Although, I must say,

they do have a marked similarity with those pictured on the Russian Archaeological

Web Museum website.

Ulalinka lithics from the Guide to the Republic of Altai

website (2014). Source not stated and no caption. Left hand specimens and

hafted point possibly from the upper cultural levels, whilst the black and white

line drawings are much more in keeping with the other sets of lithic tools

above. However, the largest flaked tool at middle, with the black

bar on it is from Fig. 3 of Derevianko

et al. (2005) and is, actually from Kara-Bom!

Firstly, I must say, I find the

typification of the stone tools by Okladnikov and Pospelova as “nearly untreated pebbles, only slightly

retouched”, quite self-serving. By emphasising their primitive aspects and

giving a scant description of their more advanced features, they are leading

the reader to their preferred conclusion: these tools are extremely old.

Secondly their statement that “The stone inventory and the techniques of

manufacture are so primitive and peculiar that they cannot be classified in the

framework of the classic Lower Palaeolithic typology. The nomenclature of the

Western European schemes cannot be applied to them.”, seems to ignore

parallels with other, ancient, tool traditions from India and Africa that the

authors must have been aware of, especially considering his own stated

familiarity with them.

Looking at what Okladnikov’s team

found, if the tools shown on Russia’s Archaeological Web Museum are from

Ulalinka, it seems to me, that even an untrained amateur can attempt an

explanation their manufacture and hence make a stab at their possible age.

Studying the images of these

tools closely I was struck by their close resemblance to a technique used on

pebble raw materials that I have seen before. To me, it seems, that they may

have been produced by bi-polar lithic reduction in addition to the use of, fire

as stated by Okladnikov.

Comparing Okladnikov’s Fig 1-4

and the specimen at right from Russia’s Archaeological Web Museum with a

schematic drawing of this technique from the Lithic Reduction article on

Wikipedia (2017), the similarities are striking:

I was extremely puzzled by this discrepancy, and thus sought

out commentaries on early lithics from central Asia and Siberia to find out

what other authors professional opinions were, about the lithics from Ulalinka.

From Shunkov (2005):

“Until recently, archaeological materials from the Ulalinka site have

been the only evidence of human occupation of the Altai during the Lower

Paleolithic. Stone tools

made of split quartzite pebbles were recovered from multi-coloured soft

sediments, which have been dated to the Middle Pleistocene and Upper Pliocene

(Derevianko et al. 1998a). An

abundant collection of quartzite rocks recovered from the lowermost layers of

Ulalinka comprise such indisputable artifacts as pebbles bearing evidence of

core preparation and negative scars of irregular detachment of amorphous

flakes. Furthermore, massive pebbles trimmed along the long axes to form

chopper/chopping tools, scraper-like tools worked on flat pebbles with a

natural back and the cutting edge formed through stepped retouch, and pebble

tools with a spur-like ovoid protruding part were recovered (Okladnikov 1972).”

Note the reference to Okladnikov

(1972). This is the original paper on the lithic tools, that caused the

controversy in Russian archaeology. The problem was that an extremely ancient

age was being claimed for the Ulalinka based primarily on the typification of

the tools. Some other Russian archaeologists strongly disputed this.

Note also the much greater detail

given. First, let us assume, for the sake of argument, that Shunkov (2005)

gives an accurate translation of the Okladnikov (1972) text. Reading this

second account, it is clear the lithic assemblage was far more diverse and

advanced in terms of the techniques of tool production used than the scant

description given by the author in the only English language paper written

about the site!

So, let us look at

the tow descriptions side by side:

Given these discrepancies I felt

I had to delve into the techniques used in the production of tools from

pebbles, to see if any research carried out since Okladnikov’s time could shed

light on these varying descriptions.

One excellent source I discovered

was Van der Drift (2009).

Van der Drift, is an amateur

scientist from the Netherlands with his own website, espousing a very

nationalistic view of the first waves of migration into his country, by ancient

hominins. His, particular, interest lies in, the lithics found there, and their

categorisation. Many specimens he, and others have collected over three

decades, do not fit the received/orthodox view of the first colonisation of the

region by Neanderthals. His view is that a much earlier, migration must have

occurred. He bases his theory on the types lithics found in this part of

Europe. Controversially, he believes, and has stated, in a number of web-based

publications that, Homo erectus/Homo antecessor/Homo heidelbergensis was

present and making stone tools, in his country, at an extremely remote epoch,

of ca. 800,000 to 1Mya.

Why use his paper? Well his

lithic samples, and his detailed explanation of the lithic techniques, used to

produce them, bear a striking resemblance to some of the lithic inventory from

Ulalinka.

In his paper, he goes into great

detail about how, he believes, ancient hominins, used the bipolar technique on

ovoid pebbles or river cobbles to produce usable stone tools.

I will highlight how his research

matches the lithics from Ulalinka.

Firstly, he states that, the

bipolar technique is used on pebbles or river cobbles of a fine grained, and isotropic

structure, such as quartz, quartzite and especially flint. This is exactly the

material used at Ulalinka.

Next he goes into great, detail

about how freehand flaking produces usable flakes, with the fracture will

always following the outlines of the core. In particular, he states that the

flakes produced, take on a well characterised, defined, conchoidal shape.

He further states: “This basic understanding of freehand

flaking, teaches us that freehand flaking does have its limitations. It is for

instance impossible to peel off flakes from a round, core (i.e. a river pebble)

because it has no striking plane, no reduction face, no edge or rib. And a

freehand blow directed to the centre will be too weak to break the core, at its

best it will produce a dead-end cone. That could certainly prove to be a great

problem for early hominids living on the edge of a river, when all they find at

the river banks are rounded pebbles.”

He then, goes on to show that the

forces exerted, on rounded river cobbles, by the freehand flaking method are

insufficient to break these cobbles. Furthermore, he shows that the use of a

hammerstone AND an anvil – the bipolar technique – are the only method by which

useable core could be prepared for further reduction.

Put simply, the application of

the bipolar technique is the only way in which river cobbles can become

prepared cores.

Putting these observations into

the context of how ancient hominins actually lived Van der Drift (2009), says “The advantage of the freehand technique is

that it produces blades and flakes in an effective, reliable, controlled way.

Because of the control that it gives, it was the technique of choice for most

hominids with access to large isotropic stones. But in the palaeolithic many

hominid groups in lowland river delta areas could not find large isotropic

stones. Instead these hominid groups had to rely on pebbles and bipolar

techniques. The industries that these hominids produced (for instance

Vértesszöllös) are called pebble-tool-cultures due to the obvious use of

pebbles as raw material. But the role of the bipolar techniques in pebble-tool-cultures

has hardly been investigated and often denied. We should get a better

understanding of the possibilities that bipolar techniques offer, few

archaeologists have even recognised that bipolar techniques offer choices. In

order to understand Pebble tool cultures and related industries we must study

the options that the bipolar techniques offered.”

His Fig. 5 shows the results of

different angles of hammer impact on pebbles:

Van der Drift (2009)

Fig. 5. Original caption reads: Figure 5: bipolar techniques A and B straight,

C oblique, D and E retouching, F contre coupe, G notching

Exploring how different hammer-stone

striking angles, affect the way pebbles shattering when the bipolar technique

is used he defines two modes of reduction: straight bipolar technique and

oblique bipolar technique, each resulting in different, shaped prepared core.

Continuing, his argument, Van der

Drift (2009) makes a crucial point: “It

is difficult to distinguish between oblique bipolar flakes and freehand flakes.

Oblique bipolar flakes never show any double contact points or double ripple

patterns. And smaller differences (i.e. different angle, striking plane,

curvature, bulb formation, bulbar scar location) are easily overlooked. This explains

why for instance László Vértes mistakingly thought that “No traces indicative

of a bipolar technique have been observed.” in Vértesszöllös. Just like any

freehand flake does, flakes made in oblique bipolar technique show only one

contact point, a sharp edge at the opposite side and they have a nearly conchoidal

shape.”

This is the main point of his

entire chain of reasoning: tools made on river cobbles/pebbles have been worked

by the bipolar reduction technique and that the results of the use of it, by

hominins on the Eurasian continent, remain, largely unrecognised.

Lastly he examines bipolar retouching

of these ‘prepared core’:

“It is possible to start out with a rounded pebble, break it open with

the nutcracker technique and as the broken pieces have striking planes and

reduction faces, you can

than proceed using freehand techniques. This is actually what D. Mania

proposes for Bilzingsleben. I do not believe that this is what happened. In

Bilzingsleben there might certainly have been some opportunistic freehand flaking,

just like in other bipolar traditions. But the majority of the further shaping

and retouching of the artifacts was done in bipolar technique, as shown in

figure 5D and 5E. This is proven by the tool shapes (discussed in my film “the

bipolar toolkit concept”) and the signals discussed

in chapter 3. The first reason for bipolar retouching is that anvils

proved to be very helpful in working steep edges, it is often still very

difficult to shape split pebbles using freehand techniques. But this is not the

only reason to use oblique bipolar percussion in shaping and retouching

implements, this choice was also greatly influenced by habit, tradition and culture.”

Lastly Van der Drift (2009),

expresses his opinion on the development of the pebble tool culture in the

middle Pleistocene:

“ ..the repeated and habitual use of bipolar techniques in the initial

shaping of pebbles must have trained the hominid mind in understanding the consequences

of bipolar reduction. Anvil use was a habit in some traditions! And it goes much

further because each step of the production line was part of the integral

tradition, from the gathering of

pebbles as raw material on the banks of a stream to the next step of

bipolar breaking and the following step of bipolar shaping to the final step of

the application of the tools. Groups using the freehand toolkit concept had the

habit of using freehand flaking on good raw material (often found on open

planes and in mountains), most often with the intent of using bifacial

reduction to make handaxes (long cutting tools) that were meant for meat and

hides processing (from large grazers in open landscapes).

Groups using the bipolar toolkit concept often lived where good raw

material was difficult to find such as forests and river deltas. They had the

habit of using bipolar reduction to make choppers, steep scrapers, deep notches

and related tools. In the early Oldowan the choppers were used directly for

food processing and this meant that the invention of long cutting tools was an

improvement and the decisive step towards the Acheulean.

But in the middle Pleistocene bipolar traditions in Europe and Asia,

the steep scrapers and notches and related tools were meant for wood and bone

processing. The combination of stone and wood and bone tools were used to

process food. So the bipolar toolkit traditions had developed a completely

different concept of suitable raw material, a completely different concept of

tool-shapes and a completely different concept of tool-use. The group or microband of hominids had a completely

different concept in their collective memory than the freehand groups. It was not

the simple cracking open of small pebbles (Mania called this Zertrümmern) but

it is this complete concept that ensured survival of the group.”

Van der Drift (2009), also

illustrates some of the lithics he believes were produced by bipolar technique.

Interestingly, these include some retouched specimens very reminiscent of those

from Ulalinka (compare the right-hand specimen from them Russia’s

Archaeological Web Museum (1999) and the bottom left specimen from Okladnikov

(1982)) :

Pebble tools, with retouch, produced

by bipolar technique from Van der Drift (2009). Original caption reads: BIPOLAR

RETOUCHING Tayac-points are converging denticulates and are most often small

(scale 5 cm.) and triangular in cross-section, they should not be compared to

handaxes which are smooth edged bifacial large cutting tools.

Reflecting back on the lithic

tools found at Ulalinka, it seems more than probable that many of the tools

found in the lowest cultural level were produced by the bipolar technique.

The tools these hominins,

produced may instead of being extremely ancient, result from an expedient use of the raw materials

found in the region. The absence of blades and points, whilst seeming to

indicate a truly ancient origin for the tools found, may, in fact indicate that

the tool-makers were simply from a different tool tradition, which used bone

points as hunting weaponry and stone tools for hide and wood working. Thus

their age may NOT be as ancient as Okladnikov (1982) believed.

Let us look now at the dating

techniques used by Okladnikov to see if the evidence he presented is strong

enough to support his ‘late Pliocene’ age for the site. He says:

“The archaeological data alone were insufficient to estimate the age of

the tools. Geological, paleogeographical, and paleontological methods were also

used, though they did not yield a common result. Some scholars, noting the

relatively low elevation of the site, thought it no older than 40,000 years,

while others dated it to the middle Pleistocene (Okladnikov 1964, 1972; Gaiduk

1968; Ceitlin 1979) and still others to the early Pleistocene on the basis of

the geological conditions (Adamenko 1970). A further group of scholars assigned

it to the late Pliocene on the basis of the paleogeographical environment and

the lithology of the cultural level (Okladnikov and Ragozin 1978a and b). The

paleomagnetic method was employed to help solve this complicated and very

important problem (Pospelova, Gnibidenko, and Okladnikov 1980; Okladnikov Pospelova,

and Gnibidenko 1981)”

The Paleomagnetic method was used

to date the stratigraphic column at Ulalinka and, in particular the clay layer

in which the oldest stone tools were found. This method relies on the fact that

lava, clay, lake and ocean sediments all contain microscopic iron particles.

When lava and clay are heated, or lake and ocean sediments settle through the

water, they acquire a magnetization parallel to the Earth's magnetic field.

After they cool or settle, they maintain this magnetization, unless they are

reheated or disturbed. The remanent magnetization, that is the magnetisation of

the rocks or sediments, from the time they were laid down can be found by the

application of suitable laboratory techniques.

The description of the number of

samples taken from the various stratigraphic layers; their special distribution

and the care taken in recording their orientation seems sufficiently detailed

and to my, admittedly, amateur eye to be professional enough to provide

reliable data.

The temporal “cleaning”

techniques applied to the samples in the laboratory; both Alternating Field

Demagnetization and Thermal Demagnetization, also seem sufficient to remove any

of the later, secondary magnetizations and reveal the characteristic Natural Remanent

Magnetization (NRM) component from when the sediment in which the tools were initially

laid down.

In summary Okladnikov and

Pospelova (1982) found two very minor Paleomagnetic reversals in the

stratigraphic column and a major Paleomagnetic reversal in the clays of the

lower cultural level.

They state:

“Thus a summary paleomagnetic section of Ulalinka was compiled after a

set of magnetic cleanings of rocks, the result for three paleomagnetic sections

complementing each other. It consists of two paleomagnetic zones. The sediments

of the upper unit comprise a normal paleomagnetic zone that can be compared

unambiguously with part of the Brunhes polarity epoch and the sediments of the

lower unit represent a reversed zone that can be attributed with nearly equal

probability to part of the Matuyama polarity epoch or an older reversal event

Its age is quite definitively older than 690,000 years.”

The authors go on to note that if

the Brunhes-Matuyama boundary is considered the dividing line between the

Pliocene and the Pleistocene then the site with its lithic implements older

that this boundary is a late Pliocene one.

Since 2009 the

Pliocene-Pleistocene boundary has been re-allocated to 2.588 ± 0.005 Ma.

The Brunhes-Matuyama boundary reversal is now dated, based on further research

to 781,000 years ago. This date has been set as the boundary between, the lower

and middle Pleistocene.

The Ulalinka site, based on Okladnikov

and Pospelova (1982) would thus be of lower Pleistocene age.

Commenting on the dating of the

site Shunkov (2005) says: “The available palaeomagnetic

and radiothermoluminescence (RTL) dates suggest attribution of the lowermost layers

at Ulalinka to a wide chronological range of c. 300 - 400 ka to 1.5 mya

(Okladnikov et al. 1985). The lower

chronological boundary seems doubtful, whereas the upper boundary is reliable,

supporting the age estimates of the Ulalinka site as older than 300 ka.”

The nearby Karama site, with comparable

lithic tools in its lowest cultural level, is provisionally dated to the final

Lower Pleistocene. The two sites may therefore be comparable in age and

presumably, were occupied by the same hominins.

Conclusions

- The Ulalinka site can be dated reliably to older than ca. 300,000 years

old.

- The tools found appeared of ancient derivation due to their primitive form.

This fact swayed Okladnikov to posit that they were extremely old, when in fact

the hominins who manufactured them were simply making expedient use of local material,

a material necessitates the use of the bipolar technique. The tools may

therefore be of any age.

- If the Paleomagnetic data collected by Okladnikov and Pospelova (1982)

are correct, then the site is older the Brunhes-Matuyama boundary reversal and

is thus of final lower Pleistocene era and somewhat earlier than 781,000 years

old

- The claim that the site is from an even earlier date of ca. 1.5Mya has

only slight evidence and unlikely to be correct

- Further research is required to establish, the exact age of Ulalinka and

whether is truly the oldest site of human occupation in Siberia

References

Archaeological Web Museum of Russia. 1999. Ancient

Altai Barrows - The Stone Age. [ONLINE] Available at:

Derevianko, A.P., et al., 2005. The Pleistocene peopling of

Siberia: a review of environmental and behavioural aspects.

Okladnikov, A.P. 1972. Ulalinka – drevnepaleoliticheskii

pamiatnik

Sibiri. [Ulalinka, Siberian Lower Paleolithic site]. Materialy

i issledovania po arkheologii [Materials and research on archaeology]

SSSR 185:7-19. (In Russian).

Okladnikov, A.P. and Pospelova, G.A., 1982. Ulalinka, the

oldest Palaeolithic site in Siberia. Current Anthropology, 23(6),

pp.710-712.

VAN DER DRIFT, J.W., 2009. Bipolar techniques in the

Old-Paleolithic. APAN/EXTER, pp.1-15.

[Accessed 1 January 2018].