The Engis 2 partial cranium was discovered in 1829 by the Dutch physician and naturalist Philippe-Charles Schmerling in the lower of the two Awirs Caves. As Schmerling approached the caves over the Plateau des Fagne, from the village of Engis, he naturally christened them the Grottes d'Engis.

The Awirs valley today, the location of the the

Engis 2 cave is not shown as it collapsed in 1993. Photo credit 27 Crags (2017)

These have since become known as

the Grottes d'Engis or Schmerling Caves. Schmerling himself, named the caves

for Engis because he accessed them from the Plateau des Fagnes, which is in the

Engis commune, above the cavities. Schmerling (1833-34) gives a detailed,

first-hand account:

From his section II Engis Caves: “Three quarters of a league northwest

of Chokier is the place known as the Awirs, located north behind the village

Engis. Vis-à-vis a former exploitation of aluminous shale, is a very steep

limestone hill, filled with crevices and openings, two of which are on the

upper part of this perpendicular cliff; but we see them without being able to

reach them from this side. We were therefore obliged to take a means of

examining these cavities more closely. Using a rope, attached above to a tree,

we were able to slide obliquely towards the foot of a first opening. A small

path stretches out at some distance, formed by the rock which advances enough

to be walked along. Grass and shrubs have multiplied spontaneously on the

sterile rock: they hide in some places the precipice that one has in front of

you.

The first cavity is 5 meters wide and 6 high at the entrance the total

depth of this cavity is 17 meters: towards the end the vault is lowered more

and more. The bottom, in the posterior part, is little covered with earth; a

small gallery exists on the right, and it is parallel to the main opening. The

bone earth, which presented the same characteristics as that of the other

caves, was very abundant on the interior part, where it was 2 meters thick; but

towards the posterior part, and in the small side gallery, there were few.

The treasures collected in this cave are: An incisor tooth, a dorsal

vertebra and a male phalanx, some remains of bears, hyenas, horses, and

ruminants; several flint sizes in triangular shape. By clinging to the walls of

the rock, we descend from this first opening to a second, after having passed

over a point of the rock, along a small path, 17 meters long. The entrance to

this cave is 5 meters high and 4 meters wide; like the previous one, it has a

view of the North. It is located one meter below the level of the first; near

the beginning of the school year are many shrubs which have grown naturally in

the bone earth. The depth of the first chamber, which is the main one, is 12

meters, over a height of 5 and a width of 4m near the entrance is a singular

separation, formed by the limestone which passes in a straight line; in this

place the cave is cut in two, in the form of an arcade. At the end of this room

there is a not very wide gallery which descends to the left, so that it

describes a semi-circle, always lowering itself; it is filled with earth

containing bones. Soon we find ourselves stopped by the little space offered by

this corridor, which ends with a small opening in which we cannot enter. On the

left side of the main opening there is a second gallery, which is difficult to

reach because of the very slippery stalactites which are at the height of a

meter and a half. After crossing this vertical entrance, you find yourself on

the limestone bench which goes almost parallel to the entrance. We see on the

right an opening which leads in the opposite direction into a small gallery,

the floor of which rises towards the south, and at the top of which is a small

chamber whose bed was strewn with bones. In addition to the stalactites which

are in this cave, one meets in the principal chamber a bony breccia; it is

placed near the gallery which is at the back; we will speak of it in more

detail in the description of human bones.

The bones of this cave were in general very dry, having the same

characters as that of the other localities; it had on the rising, a thickness

of two meters and a half, and contained bones and stones rounded and angular

throughout its height; it covered in the lower part a clayey ground more or

less compact, resting on the bottom formed by the rock, which is everywhere

very uneven.

The bones coming from this cave

have, in general, a yellowish-white tint, which varies to blackish and have

been rolled for some time before being dropped off in the place where we

collected them. It was from this cave, among other things, that I removed bones

of bears, hyenas, and several rhinoceroses, etc., which showed me that these

bones could only have been deposited there by water. Finally, on the right,

entering the second cave, is a gallery which is only a continuation of the

limestone which extends under a vault in this place, and which leads into

another gallery, the longest of all, having little height and width. Both have

provided me with bones lying in the same soil than that of the neighbouring

caves, but less numerous than in the second that we have just described.”

In section IV, ‘Human Fossil

Bones in Particular’, Schmerling recounts:

“Human bones are too well known for me to need to enter into a

detailed description of these remains. It is more important not to neglect

anything with regard to their deposit, and first of all I observe that these

human remains, which are in my possession, are, like the thousands of bones

that I have recently unearthed, characterized by their degree of decomposition,

which is absolutely the same as those of extinct species; all are broken, with

a few exceptions; some are rounded, as often occurs in the fossil bones of

other species. The breaks are vertical, or oblique, none showing traces of

erosion, the colour does not differ from that of other fossil bones, and varies

from yellowish-white to blackish. All are lighter than normal bones, with the

exception of those which are covered with a layer of calcareous tuff, or whose

cavities are filled with such concretions.

The skull which I had represented, plate I, fig. 1-2, is from an

elderly individual. The sutures begin to fade, all the facial bones are

missing, and only a fragment of the temporal bone on the right side has been

preserved.

The face and the base of this skull were removed, before it was

deposited in this place since after having regularly exploited all this cave,

we could not find these remains. It was a meter and a half deep that we

encountered this skull, hidden under a bony breccia, made up of the remains of

small animals, and containing a rhinoceros tooth, and some of horse and

ruminants. This breccia, of which we have spoken, p. 31, was a meter wide,

rising a meter and a half above the floor of the cave, and adhering strongly to

the wall.

The earth, which contained this human skull, indicated no disturbance;

rhinoceros, horse, hyena and bear teeth surrounded him on all sides.

The famous Blumenbach (1) exposed

the differences in the shape and dimensions of human skulls of different races.

This important work would have been of great help to us if the face, an

essential part in determining race with more or less certainty, were not

lacking in our fossil skull. We are convinced that, from a single sample, we

cannot at all say with certainty, even if this head would be complete, because

the individual shades are so numerous in the skulls of the same race, that one

cannot without to expose oneself to the greatest consequences, to conclude from

a single fragment of the skull for the total shape of this head.

(1) Decas Colleclionis suae

craniorum diversarum genliitm illustrala, Gotùngae, 1793- 1820.

However, not to neglect anything concerning the shape of the skull

fossil that we have collected, we will observe that the form elongated and

narrow forehead first fixed our attention.

Indeed, the little elevation of the frontal, its narrowness and the

shape of the eye sockets, bring it closer to the skull of the Ethiopian than to

that of the European, the elongated shape, and the developed state of the

occiput, are still characters which we believe to have noticed in our fossil

skull, but to avoid any doubt in this regard, I have made represent the outline

of the skull of a European, and of an Ethiopian, and the fronts shown on plate

II, fig. 1, i, same plate, fig. 3 and 4, will be enough to distinguish the

differences, and a single glance at these figures will say more than a long and

boring description.

Whatever judgment we make on the origin of the individual where this

fossil skull comes from, we can, it seems to us, express our opinion without

exposing ourselves to a controversy, the outcome of which would be without

positive result.

Each one, moreover, is free to choose the hypothesis which seems to

him the most founded; as for me, it is shown to me that this skull belonged to

an individual whose intellectual means were not very developed, and we conclude

that it comes from a man whose degree of civilization was not to be very

advanced this which we can realize by comparing the capacity of the forehead

with the occipital part.

Another skull, of a young individual, was on the bottom of this cave,

next to an elephant tooth; this skull was whole until the moment when I wanted

to collect it, it then fell to pieces that, I have not, as yet, been able to

put it together again. But I have represented the bones of the upper jaw, plate

I, fig. 5. The state of the alveoli and teeth shows us that the molars had not

yet pierced the gums. Detached milk molars, and some fragments of human skull

come from this same place.

Figure 3 shows a human upper incisor tooth, which, by its size, is

truly remarkable.

Figure 4; is a fragment of the upper jaw bone, the molar teeth of

which are worn down to the root.

I have two vertebrae, a first and a last dorsal.

A clavicle on the left side, (see plate III, figure 1); although

having belonged to a young individual, this bone announces the rather large

size of this individual.

Two fragments of radius, badly preserved, do not indicate to me that

they belonged to an individual whose dimensions exceeded the height of the man,

being five and a half feet.

As for the remains of the upper extremities, those in my possession

are limited to a fragment of ulna and radius. (plate III, fig. 5 and 6.)

Figure i of plate IV, represents a bone of the pastern, contained in

the breccia we have spoken of; it was in the lower part, above the skull; add

to this a few bones of the pastern, drawn from very different distances, half a

dozen metatarsals, three phalanges of the hand and one of the foot. Here is the

succinct enumeration of the remains of human bones collected in the cave of

Engis, which has preserved for us the remains of three individuals, surrounded

by those of the elephant, the rhinoceros, and predators of species unknown in

the present creation.”

Human fossils from the lower

Engis Cave. All except Fig. 5 were from modern humans, the maxilla, however

belonged to the infant Neanderthal, whose skull is known as Engis 2. image

credit: Schmerling (1833-4) via Orbi (2021).

Lastly, Schmerling, also realised

that, the flint objects found in association with human and animal bones were

actually man-made.

Schmerling’s publication of his

finds, with its lucid writing and huge number of beautifully drawn plates

provided a catalyst for further debate on the antiquity of man. Such luminaries

as Geoffroy St. Hilaire, William Buckland, Charles Lyell and others visited

Schmerling and examined his fossil collection.

Huxley (1863) in his book, Evidence as to Man's place in Nature, has a

chapter entitled “On Some Fossil Remains of Man”. Here he compared the Engis I

skull (Figs. 1 an 2 above) with the skull from Kleine Feldhofer Grotte in the

Neandertal valley. He compared the two skulls, then compared them to the various

‘races’ of man. He explores the shape of the face, the dimensions of the

various skulls, their development of the supraciliary ridges a, from such

populations as Australians, Tartars, Danish, Negros, Calmucks (Mongolians) and “and

of a well developed round skull from a cemetery in Constantinople, of uncertain

race, in my own possession”. He also compared cranial capacities, where

available. In conclusion he writes:

“But taking the evidence as it stands, and turning first to the Engis

skull, I confess I can find no character in the remains of that cranium which,

if it were a recent skull, would give any trustworthy clue as to the Race to

which it might appertain. Its contours and measurements agree very well with

those of some Australian skulls which I have examined—and especially has it a

tendency towards that occipital flattening, to the great extent of which, in

some Australian skulls, I have alluded. But all Australian skulls do not

present this flattening, and the supraciliary ridge of the Engis skull is quite

unlike that of the typical Australians.

On the other hand, its measurements agree equally well with those of some European skulls. And assuredly, there is no mark of degradation about any part of its structure. It is, in fact, a fair average human skull, which might have belonged to a philosopher, or might have contained the thoughtless brains of a savage.

The case of the Neanderthal skull is very different. Under whatever

aspect we view this cranium, whether we regard its vertical depression, the

enormous thickness of its supraciliary ridges, its sloped occiput, or its long

and straight squamosal suture, we meet with ape-like characters, stamping it as

the most pithecoid of human crania yet discovered…

In no sense, then, can the Neanderthal bones be regarded as the

remains of a human being intermediate between Men and Apes. At most, they

demonstrate the existence of a man whose skull may be said to revert somewhat

towards the pithecoid type...

And indeed, though truly the most pithecoid of known human skulls, the

Neanderthal cranium is by no means so isolated as it appears to be at first,

but forms, in reality, the extreme term of a series leading gradually from it

to the highest and best developed of human crania. On the one hand, it is

closely approached by the flattened Australian skulls, of which I have spoken,

from which other Australian forms lead us gradually up to skulls having very

much the type of the Engis cranium. And, on the other hand, it is even more

closely affined to the skulls of certain ancient people who inhabited Denmark

during the 'stone period'..

The correspondence between the longitudinal contour of the Neanderthal

skull and that of some of those skulls from the tumuli at Borreby, very

accurate drawings of which have been made by Mr. Busk, is very close. The

occiput is quite as retreating, the supraciliary ridges are nearly as

prominent, and the skull is as low. Furthermore, the Borreby skull resembles

the Neanderthal form more closely than any of the Australian skulls do, by the

much more rapid retrocession of the forehead. On the other hand, the Borreby

skulls are all somewhat broader, in proportion to their length, than the

Neanderthal skull, while some attain that proportion of breadth to length

(80:100) which constitutes brachycephaly.

In conclusion, I may say, that the fossil remains of Man hitherto

discovered do not seem to me to take us appreciably nearer to that lower

pithecoid form, by the modification of which he has, probably, become what he

is. And considering what is now known of the most ancient races of men; seeing

that they fashioned flint axes and flint knives and bone-skewers, of much the

same pattern as those fabricated by the lowest savages at the present day, and

that we have every reason to believe the habits and modes of living of such

people to have remained the same from the time of the Mammoth and the

tichorhine Rhinoceros till now, I do not know that this result is other than

might be expected.

Where, then, must we look for primaeval Man? Was the oldest 'Homo

sapiens' pliocene or miocene, or yet more ancient? In still older strata do the

fossilized bones of an Ape more anthropoid, or a Man more pithecoid, than any

yet known await the researches of some unborn palaeontologist?

Time will show. But, in the meanwhile,

if any form of the doctrine of progressive development is correct, we must

extend by long epochs the most liberal estimate that has yet been made of the

antiquity of Man.”

Despite the fact that Huxley was a diligent and thoughtful scientific

investigator, by the standards of his day, there is a double irony attaching to

his assessments of the fossils he chose to discuss.

Firstly, less than a year later, King

(1864a and b), published his assessment of the Kleine Feldhofer Grotte cranium

as a new species, namely Homo

neanderthalensis. Secondly, the other skull collected at lower Awirs cave

was, although juvenile, actually a Neanderthal too. So near, but so far in

terms of your name living on in scientific posterity!

A diagnosis of the Engis 2 cranium

as a Neanderthal would not be written until, over a century later, by Fraipont,

(1936). The lower of the Engis caves was investigated by numerous excavators

over the next 125 years. These included

archaeological investigations: in 1868 by the geologist Éd. Dupont, in

1885 by the palaeontologist J. Fraipont, then by other people such as É. Doudou

from 1895 onward and J. Hamal-Nandrin in 1904; finally, over the 20th century,

by teams from the 'Chercheurs de la Wallonie' association, notably in 1907 and

1956.

Although, the Engis 2 cranium had been assigned to Homo Neanderthalensis early in the 20th

century, Tillier (1983) provided a modern analysis. She concludes her study of

the Engis 2 cranium thus:

“During our study we compared the metric and morphological data of the

skull of Engis 2 with those of other Neanderthal children and with those of a

sample of current skulls whose dental age was between 5 and 10 years. Some

initial remarks can be made regarding the development of the Neanderthal skull.

Among the dimensional characteristics of the skull of Engis 2 which

deviate from the data collected on current subjects we can retain the frontal

width and the interorbital width the biporic width, and the biasteric width,

the maximum width of the skull: all these measurements are large on Engis 2

while the bimastoid width, for example, remains close to the current average

value. In addition to these dimensions, the lambdoid parietal curvature index

and the sagittal occipital curvature index are lower on Engis 2.

Certain metric characters of the skull of Engis 2 contrast with the

data known in Neanderthal adults. Thus the bregmatic and frontal Schwalbe

angles, the sagittal parietal curvature index are placed outside the variation

limits for adults. Such an arrangement is found for the frontal on the

Teshik-Tash skull while the sagittal parietal curvature index corresponds to

the lower limit of adult Neanderthal variation. On the temporal on the other

hand, the height / length index of the scale and that giving an idea of the

development of the mastoid process in relation to the length of the scale

distance Engis 2 from Neanderthal adults and bring it closer to current

children.

Most of the derived morphological characters retained on the skull of

the adult Neanderthal are already recognizable in the child of Engis 2. as

shown by the parietal. the occipital and the temporal. The morphology of the

maxillo-malar region in extension can be considered without being demonstrated

(in the absence of bone support); the study of the maxilla of Gibraltar 2

(Tillier 1982) found on the other hand, that the development of maxillo-malar

angulation could be variable.

Some characters, in relation to the young age of the subject, are only

sketched out on Engis 2, such as the suporbital torus, the separation of the

petrotympanic crest and the mastoid process, or absent such as certain

occipital temporal reliefs and frontal pneumatization.

Finally, other characters, present on Engis 2, have no significant

value from a phylogenetic point of view, such as the relative development of

the posterior zygomatic tubercle, the great width of the digastric groove or

the small size of the teeth (except of dc M1 and dm2).

The attribution of the skull of

Engis 2 to the group of Neanderthals cannot therefore be called into question.

He represents with the men of Spy, with whom he shares certain characteristics

such as the width of the digastric groove and the relative development of the

posterior zygomatic tubercle (Spy I) or the single suprasiniac fossa (Spy 2),

the best-known representatives of this evolutionary morphological stage in

Belgium. Engis 2 also constitutes a reference element in the ontogenetic study

of the Neanderthals, the importance of which can no longer be neglected.”

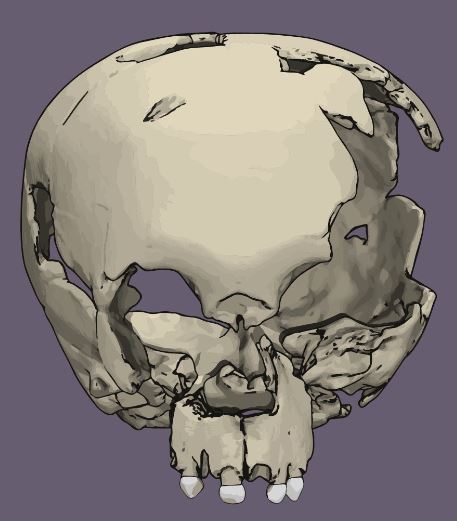

Tillier (1983) showing the

principle frontal sutures. Original caption reads: Norma frontalis of the skull

of Engis 2 showing the outline of the supraorbital torus.

Rear view of the occipital region of Engis 2 showing the spreading of the supra-iniac fossa and the insertion of large complexus [broad muscle lying along the back part of the neck, connecting the occiput and the lower cervical and upper dorsal vertebræ].. From Tillier (1983).

The dates for the Engis 2, Neanderthal infant have been somewhat contentious.

Toussaint and Pirson (2006) obtained dates of ca. 26,820 and 30,460 BP on

cranial fragments. These are regarded as too young.

Even the author [Toussaint (2011)] comments: “As for

chronostratigraphy, the only information available comes from radiocarbon

dating. Two contiguous fragments of the left parietal of the Neanderthal child

thus provided two dates (Toussaint & Pirson, 2006a). The first, 26,820 ±

340 B.P. (OxA- 8827; delta 13C = -19.3), is far too recent in view of the

regional and north-western European context to be acceptable. Even the second,

30,460 ± 210 B.P. (GrA-21545), hardly makes sense in the archaeological context

from the Bassinmosan where such a date is more in phase with a fairly old

Aurignacian.”

Devièse et al. (2021)

finally achieved more reasonable dates for Engis 2. The researchers took

collagen samples from Neanderthal skeletal remains originally found in 1829.

While taking collagen samples for radiocarbon dating is a standard

technique used to date fossils, the researchers had to use an advanced

purification method Using liquid chromatography in order to separate the

collagen samples from all contaminants. They found that the contaminants

arising from the actual methods of preservation themselves, including glue

prepared from bovine bones used to preserve skeletal remains had affected the

radiocarbon dates, making them appear too young.

Using this process, the researchers were able to isolate just one

molecule — a single amino acid — in order to increase the accuracy of the

radiocarbon date read.

Based on these new radiocarbon dates, the authors of the study estimate that the Neanderthal child, Engis 2, dates to between 40,600 and 44,200 years ago.

Other parts of the Engis assemblage have also provided a greater depth of understanding, in terms of Neanderthal child development. In particular, the partial mandible found, and illustrated by Schmerling (1833-34) has been studied in depth.

The Engis partial mandible found by Schmerling from Parg, (2015).

Futher research has included an ontogenetic analysis was carried out

by Smith et al. (2010). In this very

illuminating study, a new age at death was calculated for the Engis 2

Neanderthal child, using the unerupted teeth in the mandible recovered from the

lower Engis cave. The authors explain the variables they measured and how these

result in an accurate age at death, they stated: “To calculate crown formation

time, molar eruption age, and age at death, we quantified the following

standard developmental variables: cuspal enamel thickness, long-period line

periodicity (number of daily increments between successive long-period lines),

total number of long-period lines in enamel (Retzius lines or perikymata), and

coronal extension rate (speed at which enamel forming cells are activated to

begin secretion along the enamel-dentine junction) in 90 permanent teeth from

28 Neanderthals and 39 permanent teeth from 9 fossil H. sapiens individuals…

Combining histological data on initiation ages, crown formation times,

and root formation times yields age-at-death estimates for six Neanderthal and

two fossil H. sapiens juveniles.” They arrived at an age of 3.0 years for the

Engis 2 Neanderthal, individual, at death.

Scan of the Engis 2 maxilla,

showing unerupted permanent incisors and canines, from Smith et al. (2010).

Original caption reads: Fig. 1. Virtual histology of the maxillary dentition

from the 3-y-old Engis 2 Neanderthal. (A) Synchrotron micro-CT scan (31.3-μm

voxel size) showing central incisors in light blue, lateral incisors in yellow,

canines in pink, and third premolars in green. (Deciduous elements are not

rendered in color as they were not studied.). Scale bars in A and B, 10 mm.

To this day the Engis 2, cranium of the Neaderthal child justly, fascinates archaeologists and palaeoanthropologists and the public alike. It is a poignant relic of a life cut brutally, short. I wonder what the youngster thought and felt in the months leading up to their untimely demise? Did they play along the banks of the Awirs stream below and was it some chance accident or disease, that brought about their death? Did their parents bury them in the cave with as much grief as a modern family would have? These are the unanswerable questions that haunt me.

Engis 2 virtual reconstruction by John Hawks (2021) – I wonder

what he or she looked, in the flesh?

References

27 Crags (2017). At: https://27crags.com/crags/awirs/photos accessed 19/08/2021

Devièse, T., Abrams, G., Hajdinjak, M., Pirson, S., De

Groote, I., Di Modica, K., Toussaint, M., Fischer, V., Comeskey, D., Spindler,

L. and Meyer, M., 2021. Reevaluating the timing of Neanderthal disappearance in

Northwest Europe. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 118(12).

Fraipont, C. (1936) Les hommes fossiles d'Engis. Archives de

l'institut de Paléontologie Humaine. Memoire, 16: 52 p.

Hawks, J. (2021). Neanderthals. At: https://twitter.com/johnhawks/status/1367226871948185603

accessed 18/08/2021

Huxley T. H. (1863). On Some Fossil Remains of Man, in Evidence as to Man's place in nature.

Williams & Norgate, London.

King, W. (1864a). On the Neanderthal Skull, or Reasons for

believing it to belong to the Clydian Period, and to be a species different

from that represented by Man, Report of the British Association for the

Advancement of Science. London. 33rd Meeting (1863), p81-82

King, W. (1864b). The reputed fossil man of the Neanderthal.

Longmans Green & Company.

Orbi (2021). Recherches sur les ossemens fossiles découverts

dans les cavernes de la province de Liège. Down load at: https://orbi.uliege.be/handle/2268/207986

accessed 17/08/2021

Parg, P. (2015). Engis 2 Maxilla. At: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Engis_2_Maxilla.jpg

accessed 18/08/2021

Schmerling P.-C. (1833-34) – Recherches sur les ossemens

fossiles découverts dans les cavernes de la province de Liège, P.-J.

Collardin, Liège, 2 tomes de 167 et 195 p.

Smith, T.M., Tafforeau, P., Reid, D.J., Pouech, J., Lazzari,

V., Zermeno, J.P., Guatelli-Steinberg, D., Olejniczak, A.J., Hoffman, A.,

Radovčić, J. and Makaremi, M. (2010). Dental evidence for ontogenetic

differences between modern humans and Neanderthals. Proceedings of the National

Academy of Sciences, 107(49), pp.20923-20928.

Tillier, A.-M. (1983)

Le crâne d'enfant d'Engis 2: un exemple de distribution des caractères

juvéniles, primitifs et néanderthaliens. Bull. Soc. roy. belge Anthrop.

Préhist., 94 :51-75.

Toussaint M. and Pirson S. (2006). Neandertal Studies in

Belgium : 2000-2005. Periodicum Biologorum, 108: 373-387.

Toussaint, M., Semal, P. and Pirson, S. (2011). Les Néandertaliens du bassin mosan belge: bilan 2006-2011. Le Paléolithique moyen en Belgique, pp.149-196.

No comments:

Post a Comment