The Cerne Abbas Giant is perhaps the most well-known of the chalk figures of England. Approximately 60 have been etched on the landscape with less than a third being dug out in antiquity. The Rude Man of Cerne with his 5m erection, stands proud above the rest, in notability.

The Cerne Abbas Giant stands 180 feet tall. Picture originally from the National Trust (2016) website (image now removed).

The Cerne Abbas Giant seen from the air in ca. 1991 from Papworth (2020j). Original caption reads: The Trendle is just visible as a rectangle above the Giant’s head on the crest of the down.

To keep him visible, to public view he needs ‘scouring’ and

re-chalking approximately every seven to eight years. In centuries past the

people of Cerne Abbas and surrounding villages, came together to accomplish the

task. And after? – why there was merriment, dancing and games around the

maypole, in the Trendle above. Nowadays, under the National Trust’s benign ownership

he gets his facelift on a regular basis.

National Trust volunteers scouring the Giant in 2019. Original caption reads “Volunteers helping to re-chalk the Cerne Abbas Giant” from National Trust (2021b).

Various theories have been put forward as to the origin of the

Geoglyph: was he an Iron Age fertility symbol, a Roman representation of

Hercules, or a parody of 17th-century politician Oliver Cromwell?

However, as there is no mention of the figure in a 1540s survey of the

Cerne Abbey lands, nor in a 1617 survey conducted by the English cartographer

John Norden, most archaeologists, lean towards a post-medieval date, for the

creation of the Cerne Giant. The accepted orthodoxy was that it was first dug

out, sometime in the 1500’s similar to the Long Man of Willmington. However a

significant minority still took an alternate view that the figure was created

in the Iron Age or even late Bronze Age like the Uffington Horse.

While the origins and significance, of the figure and the meaning

attached to it by the people that built it, are cloaked by the mists of time,

the giant has become a beloved fertility symbol. According, to local folklore,

couples who make love on the aforementioned appendage, are guaranteed to conceive.

Despite the original meaning and usage of the figure being unknown, scientists have worked hard to discover when the turf was original removed. One complication is that the figure has to be ‘re-chalked’ every few years so that it remains visible. The process involves removing any invading herbage and then pounding chalk quarried from nearby, into the trenches that make up the figure. Therefore scientists needed to study the very base of the deposit.

As Papworth (2020l), explains the project is a very long time in

coming to fruition: “Minutes of the National Trust meeting 3rd February 1994...

Action: to organise a meeting between all the interested parties and together

build a research project to enable us to get a date for the Giant. After four

years of consultation the research design was created and agreed.

It would include a detailed contour survey of Giant Hill, a review of

the local landscape archaeology and documentary evidence…. but particularly

excavations across the deeper stratigraphy, clearly visible from a build-up of

sediments at his feet.

This would be the best place to get the samples to obtain an optically stimulated luminescence date (OSL) …but the funding failed…. The research design document stayed in the files….. It remained as evidence of what might have been.”

LiDAR image of Cerne Giant and

Trendle earthwork, where a maypole was erected and celebrations may have taken

place, to accompany the seven-yearly scourings of the figure. From Papworth (2020i),

original caption reads: The processed LiDAR image of the Cerne Giant with the

Trendle earthwork above him clearly outline. A rectilinear structure, probably

building footings can be seen in the centre of the earthwork and top left what

look like prehistoric rectilinear field boundaries approaching the enclosure.

On the Giant, the pronounced earthworks from soil settling on his horizontal

lines can be seen on his elbows and feet as lines of yellow and his nose,

recreated in 1993, glows bright yellow.

Papworth (2020l) continues: “22

years later and we approached another centenary. This time the Giant’s

centenary. I asked again and Hannah the General Manager said ‘yes, let’s do it

…. This is the Cerne Giant’s acquisition centenary year!”

In March 2020, the archaeologists traveled to the hilltop site in Dorset, to begin their investigations of the Cerne Giant. As indicated by the LiDAR results, they dug trenches in the areas of greatest soil settlement: his elbows and feet. They record the layers as they dug. These they related to known scourings of the Giant until they reached horizons, beyond, known history. Here, just above the untouched bedrock, they took samples of soil, that had not seen the light of day since the Giant was first created. These OSL (Optically Stimulated Luminescence) samples can give an age for the last, exposure to sunlight, of the quartz grains in the soil sample.

Archaeologists at work attempting to find an age for the Cerne Abbas Giant. Clockwise from the top left archaeologists seen trenching the left and right feet down the length of the Giant’s shaft, Papworth (2020e); Martin Papworth recording trench profile during the excavation, National Trust (2021a); Cerne Giant excavation sites, left and right elbow and feet, original caption reads: showing the sites of the 4 excavations clockwise from bottom right trenches A B C and D (photo John Charman Cerne Historical Society) Papworth (2020i); archaeologist labelling OSL samples, original caption reads: Prof. Phillip Toms, Academic Subject Leader in Environmental Sciences at the University of Gloucestershire, labels samples. From BANR (2021); Archaeologists Mike Allen and Julie Gardner bag soil samples to find tiny snails to give palaeoenvironmental evidence, BANR (2021).

Papworth

(2020g) describes the excavation of the four trenches (A – D): “The diggers

assemble from the four trenches.

They

gravitate towards Trench B. where Carol is investigating the sole of the

Giant’s right foot.. Nancy rises up from the left foot (Trench A) and Pete and

I pull ourselves out of our excavations and slide down the hill from the

elbows. C is carved into the club wielding right arm and I am at D, the

outstretched arm.

How do our

trenches compare? We sip tepid coffee from cooling thermos flasks. The sun is

sinking.

Yes, we each

have the three compacted chalk layers 2019, 2008 and 1995 pummelled by steel

tampers once wielded by National Trust rangers, volunteers and wardens. They

crush the top of a 0.3m deep cutting, filled with ‘kibbled’ fragments, placed

there perhaps in two phases 1979 and 1956 courtesy of E.W Beard, contractors of

Swindon. They first proved their worth as the re-chalkers of the Uffington

White Horse in Oxfordshire (another National Trust property). The Ministry of

Works recommended them.

Further

down, below a rammed layer lies the chunky chalk. I have it 0.2m deep but the

others have lost much of theirs. Cut away by the kibbled events. Below this is

the thin crust which caves into the soft silty chalk… we all have this up to

0.1m deep.

Carol says

this scrapes away onto the more solid pasty chalk. I mention the bluey brown

film on the top of this and we all nod sagely.

Peter interjects

“but what of the lower chunky chalk”.

We are amazed… beneath the ‘pasty’ layer there lies a greater and deeper chunky chalk with lumps just as large as in the upper deposit…but this time… mixed with flint nodules. When this is dug out…. it is up to 0.3m deep and probing through this we hit proper geological chalk.”

So nine layers were found in

total with a combined depth of ca. 80cm.. much, much deeper than soils found on

chalk slopes which are typically of only 20 – 30cm in depth. This was unexpected

and caused much (professionally suppressed) excitement amongst the

archaeologists. Over the next couple of days, Martin Papworth drew and recorded

the sections for each trench and Mike Allen, collected soil samples (hopefully)

containing snails to gain information on the palaeoenvironment. On the final

day (20th March 2020), Philip Toms extracted the OSL samples and the

trenches were backfilled.

The curious feature, below the

Giant’s outstretched left hand were also investigated: “Mike was augering the

low grassy mound of the severed head. I went over and inspected his soil

column. Definitely an archaeological feature, we would have to do some

geophysics before deciding whether further excavation was justified.” Papworth

(2020k). Results, so far, have not been forthcoming.

What happened next is familiar to

us all, but still remains, a surreal, unprecedented experience: the worldwide

pandemic began its fast climb to a horrific fist peak.

Consequently, soon after the

samples were taken COVID19 hit home in the UK, in earnest: Martin Papworth from

Current Archaeology (2021): “As we drove away from the site on 20th March,

Prime Minister Boris Johnson announced the first stage of COVID-19

restrictions, closing pubs, restaurants, and hotels – but we did not appreciate

how much more would change. By the following Monday, our OSL samples had

reached the laboratories of Gloucester University and were ready to be

analysed, but with the announcement of full lockdown, there they have sat ever

since.”

Whilst the big institutions, like

universities furloughed their staff, Mike Allen was a private contractor,

working from home. His soil samples were with him at home. Therefore, he could

set about analysing them unlike the OSL samples professor Toms from the

university of Gloucestershire, had collected.

Throughout the spring of 2020, Allen

washed the soil samples and laboriously plucked out hundreds of half-millimetre-sized

snail shell fragments from the mud. These he identified to species based on

minute differences in whorl patterns, lines, and hair pits.

Snails are not typically used as

a dating technique, but Allen can roughly estimate when a geoglyph was formed

based on historic snail migration. Around the first century, Romans imported

certain fleshy snails to Britain to eat as escargot, whereas later snail

species hitched a ride on hay packed into medieval merchant ships.

In the giant’s earliest layer, Allen found two mollusc species regarded as medieval immigrants – Cernuella virgata and Candidula gigaxii. These snails were not present in the soil that predates the Cerne Giant. So, Allen concluded the figure was probably early medieval or later.

Snail shells identical to those

above were found in the lowest and oldest sediments collected from Cerne Giant,

from Discover Magazine (2020). Original caption reads: Remnants of snails of

the Cernuella virgata species (whose shells are seen here) suggest the Cerne

Abbas Giant first appeared on a Dorset hillside in England’s early medieval

period. (Credit: H. Zell/Wikimedia Commons).

The soil samples did give

interestingly give some important palaeoenvironmental information, which was

their original purpose.

Allen says “We can divide our

samples into those that are early and may pre-date the Giant, those that are

early and contemporary with the Giant, and those that are later (and obviously

still contemporary with the Giant). Of the species we identified in the

samples, the majority are typical of open short-grazed calcareous downland

similar to the pasture we see around the Giant today. However, some samples

yielded shells belonging to snails that do not thrive in these dry habitats.

There appears to have been a possible phase after the Giant was carved on the

chalk hillside when the slope may have been covered in long, unkempt, and

ungrazed grassland and shrubs, such as hawthorn and blackberry, which may have

possibly partly obscured the figure. In a subsequent phase, though, a community

of land snails liking short, dry, grazed grassland seems to return, suggesting

that this lush environment did not last.”

A more precise date for the Cerne

Abbas Giant’s construction would have to wait over a year until the end of the

first lockdown and subsequent reopening of university laboratories.

The above six paragraphs have

been extracted from interviews and reportage of Allen’s analysis from Discover

Magazine (2020), Allen (2020) and Current Archaeology (2021).

Up to this point in the tale of

when the Cerne Abbas Giant was created, the Medieval period had not been a

favourite in terms of a likely era for its construction. The problem was that

the historic documentation reporting the Giant’s presence on his Dorset

hillside, was sparse and quite late in date. However, I must point out that

‘absence of evidence is not evidence of absence’. Many Medieval chronicles are

only known from references in the extant literature or small fragments. Many

are entirely missing or even unknown. It is therefore entirely possible that

references to a remote and obscure region such as rural Dorset have

disappeared.

I will try to list those that we

do know of to assess whether a Medieval origin for the Cerne Giant is a

reasonable possibility.

The Cerne Giant as a Medieval, Saxon Hill figure

Accounts of the village of Cerne

Abbas as a resistant centre of pagan religion and worship, predate the sources

normally cited by hundreds of years. Goos (2013) collects various texts to support his

theory that Helith was an Anglo-Saxon God.

The first text concerning Cerne

Abbas is by Goscelin (ca. 1099). According to Goos (2013), “Goscelin (also

called Gotselin or Jocelyn), was a Benedictine monk and writer of many

biographies of English saints. Born in the north of France, he was brought to

England likely in 1053 by Hermann, Bishop of Salisbury. To collect material for

his biographies, he travelled a lot through England, visiting many cathedrals

and monasteries. He died about 1099.”

Goscelin Historia minor de vita

S. Augustini (in Wharton (1691)) writes in extremely difficult Medieval

Latin:

“Ibi quoque oratorium in perennem memoriam dominicae visionis molitus est in nomine Domini salvatoris. Inde etiam nonasterium in honorem principum Apostolorum Petri dedicatum Cernelium est appellatum, quod constat monachorum choro decoratum. Illum autem fontem Augustini nomine consecratum credentibus esse saluberrimum, hie unum docebat miraculum, teste provincia palam declaratum.”

Goos (2013) does not attempt a

translation, however, as the text is so short I attempted one. Several

difficulties were encountered. For instance, ‘nonasterium’ is not a Latin word,

it should read monasterium. The mistaken first letter (m) is simply due to

early English typefaces having an extremely thin left hand rising stroke for

the start of the M. Secondly, Illium of course means Troy, but in the Wharton,

original the word is ‘Illum’ which means ‘it is’. Thirdly the meaning of the

word ‘choro’ has changed subtly over the centuries. Where once its meanings

included praise, today it translates as dance! Here is my best guess:

There too is an oratory [small chapel or prayer room] in perennial memory of the vision roused in the name of salvation. Then even a monastery founded in honour of the Apostle Peter called by name Cernelium [Cerne Monastery] by the monks. If we believe the source, one removed from Augustine of Canterbury it was in this district that the miracle of the fountain was performed.

Although I have cited Goos (2013), the basic scholarship on early

ecclesiastical texts was carried out by various 14-18th century

learned men: early Historians if you will. These were then often collected in

turn by learned societies of England such as the Society of Antiquaries

(London) and county equivalents such as the Dorset Natural History and

Antiquarian Field Club (DNHAFC).

In fact the Latin text above may have been drawn by Goos (2013) from

this latter source, as it is identical, including the mistaken ‘n’ in

monasterium and the misspelling of illum as ilium. Unfortunately, it seems that

the DNHAFC (1901) were unable to translate the Latin either, as below their

identical text, they append the comment: “Goscelin was a picturesque writer.”

This almost certainly indicates that it was indecipherable to their worthies

too.

The DNHAFC (1901) source for the works of Goscelin is almost certainly Warton (1691) as he seems to be the earliest transcription from the original as Hayward (2004) points out: “The works on Augustine also survive in a shorter format: Historia minor de vita S. Augustini, ed. H. Wharton, in Anglia sacra, London 1691, ii. 51–71.”

Goscelin also wrote a second text on the subject in Liba Major de Vita S. Augustini (in Mabillon (1668)):

“Ibi plebs impia tenebris suis excaecata, et divinam lucem exosa, non solum audire nequibat vivifica documenta, verum tota ludibriorum et opprobriorum tempestate in sanctos Dei debacchata, longe proturbat eos ab omni possessions sua, nee manu pepercisse creditur erfrenis audacia. At Dei nuntius juxta dominicum praeceptum et apostolorum exemplum, excusso etiam pulvere pedum in eos, dignam suis mentis sententiam, non maledicentis voto, qui omnium salutem optabat, sed divino judicio, et Heliae typo atrocibus injecit : quatenus Sanctorum contemptores tarn in ipsis quam in omnibus posteris suis debeta paena redargueret, qui vitae mandata repulissent. Fama est illos effulminandos prominentes marinorum piscium caudas sanctis appendisse ; et illis quidem gloriam sempiternam peperisse, in se vero ignominiam perennem retorsisse, ut hoc dedecus degeneranti generi, non innocenti et generosae imputatur patriae.”

In English, this reads:

Here the sinful people dazzled themselves by darkness, and hate the divine light, not only in what is spoken, but also in what is written. Truth was totally ridiculed and God’s Saints were scorned and were booed. They took away all their property and inheritance, no hand or idea was saved. But the news of god’s commandment and the example of the apostles, who shook off the dust of their feet against them, because they were worth their punishment, yet they were not injured, because they wished them all salvation and they were consigned to the divine judgment, so that Helio (Heliae) and his followers irrespective of their holiness would know the scope of their penalty, both for themselves as for their posterity, because of their rejection of the precepts of life. And it is said that they who came out of water by the fish, were desirous for sanctity and they have received now eternal holiness, because they were able to dispose themselves from the permanent stigma, in spite of the fight which they were imposed of by the country who rejected frankness and generosity.

Here we see the first mention of the God that the pagans of the region worshipped: Helio. Whether the Cerne Giant is connected to this God is an open question. What exact, source Goscelin used is unknown, however we do know the dates between which it was written. This is because Augustine of Canterbury, was previously the prior of a monastery in Rome when Pope Gregory the Great chose him in 595 AD to lead a mission. These were known as Gregorian missions, in this case Augustine was sent to Britain to Christianize King Æthelberht and to carry the word of the Lord to the populance generally. He accomplished the first task successfully, but the second task of converting the Saxon, populance proved far more difficult as the incident at Cerne shows. Augustine died in 604 at Canterbury. The chronicle of his life must therefore have been written between 605 and 1091. We know that this document existed and Goscelin consulted it from Alston (1909): “In 1098 he went to Canterbury, where he wrote his account of the translation of the relics of St. Augustine and his companions, which had taken place in 1091.”

Portrait labelled "AUGUSTINUS" from the mid-8th century Saint Petersburg Bede, though perhaps intended as Gregory the Great. Wikimedia Commons.

Writing a little later William of Malmesbury (1125) records virtually, the same story of Augustine at Cerne. Only a short excerpt is included here:

Sed loco illo virtus hesit demonis conflata invidia qui tantis animarum lucris doleret. Aggrediuntur ergo virum et sotios furiatis mentibus incolae, et magnis dehonestatum injuriis, ita ut etiam caudas racharum vestibus ejus affigerent, impellunt, propellunt, expellunt.

Translated:

So Augustine took on the county I have named, and increased the number of Christians by taking frequent plunder at the Devil’s expense. But here his virtue met a check. For the Devil’s envy was aroused at such a wholesale winning of souls. The locals accordingly assaulted the man and his companions in a transport of rage, insulted him with sore injuries, even attaching ray fish tails to his clothes and pushed him on and away.

A notable omission is the name of the deity, whom the Saxons worship.

Instead Walter of Malmesbury substitutes the word Devil. Some have asserted

that William of Malmesbury did so because he wanted to demonize the pagan God.

However, removing Saxon names and Latinizing them was his normal practice he

simply wanted to make a point by making his writing conform to the ideas and

customs of the Latin Church. The original is housed at Magdalen College Oxford,

and is the oldest autograph in Britain. It is notable that there are distinct

similarities between the writings of Goscelin and Walter of Malmesbury, with

some scholars arguing that they both used the same source which has disappeared

in the depths of time.

Page 11 from Malmesbury’s De Gestis Pontificum Anglorum. Creative

commons license included in picture.

The next source that we come to

chronologically is Walter of Coventry (1293), an otherwise unknown monk probably

of the diocese of York. He writes:

In Dorsetensi pago sunt abbatiæ Kerneliensis, Middiltunensis virorum;

Sceaftoniensis feminarum; in quo pago olim colebatur deus Helith; sed prædicans

ibidem verbum Dei Sanctus Augustinus vidit mentis oculo Divinam adesse præsentiam,

hilarisque factus ait, “Cerno Deum, Qui nobis Suam retribute “gratiam:” eventus

vel potius verbum Kernelliensi loco indidit vocabulum, ut vocaretur Kernel, ex

duobus verbis Hebraico et Latino; quod Hel Deus dicatur Hebraice. Ibi

succedentibus annis Edwoldus frater Edmundi regis et martyris vitam heremiticam

solo pane et aqua trivit: post vero religiose actam vitam magna sanctitatis

opinione ibidem sepelitur. Cui succedens Aedwardus homo prædives cænobium eo in

loco Sancto Petro construxit.

Translation: In the county of

Dorset are the abbeys of Cernel [Cerne] and Middleton [Milton]; and the nunnery

of Shaston [Shaftesbury]; and in this county the God Helith was once worshipped; but preaching the word of God in that

same place, St. Augustine saw in his mind’s eye a divine presence, and having

become overjoyed he said, ‘I discern God, Who will restore His grace to us:’

this event or rather word gave its name to the location of Cernel, such that it

is called Cernel from two words such that it is called Cernel from two words,

one Hebrew and one Latin; because El is what God is called in Hebrew.

Although the last supposition of

the origin of Cernel [Cerne Abbas] for the village name, is ludicrous, we see

here another reference to the deity worshipped: Helith. The spelling may be different, but the likelihood of two

Saxon Gods beginning with the letter H, being worshipped in the same, small

Dorset village seems remote.

The next source we have for Cerne Abbas and its pagan worshippers is

John Leland (1549). In fact it was Leland who discovered Walter of Coventry’s

manuscript in 1538. Stubbs (1872) explains the circumstances of Leland’s

discovery and his usage of it thus: “The indefatigable Leland, on his journey

of investigation into the antiquities of his country, between the years 1538

and 1544, discovered, unfortunately he does not tell us where, a large

manuscript of historical collections, on one leaf of which was the inscription "Memoriale Fratris Walteri de Coventria."

The book, he saw at once, was mainly a compilation from Geoffrey of Monmouth,

Henry of Huntingdon, Marianus Scotus,

and Roger of Hoveden: but he saw also that it contained a good deal of matter,

especially on the events of the years 1170 to 1177, and 1201 to 1225, which was

not derived from the authors he mentions, and which therefore he regarded as

being most probably the work of the person whose name the manuscript bore. On

this account he inserted a notice of Walter of Coventry in his Commentaries on

the writers of Britain.”

Furthermore, he states: “This manuscript, since Leland discovered it, has had an uneventful history. The great antiquary seems to have possessed himself of it, and to have made his extracts from it at his leisure.”

One of his extracts from Walter of Coventry reads: “Deus Helith colebatur in pago de Cernel,

tempore Augustini, Anglorum apostolic.”

Translated: “The god Helith was worshiped in the village of Cernel in the time of Augustine, apostle of the English.”

John Leland by Thomas Charles Wageman (Public Domain via Wikipedia).

Our next source is

William Camden (1551-1623). Son of a middle-class artisan, he attended St.

Paul’s School and Magdalen College, Oxford and developed antiquarian interests.

Returning from Oxford to London without a degree (for whatever reason) he

became usher of Westminster School in 1575. This position allowed him to travel

extremely widely throughout England during school recesses and collect

antiquarian materials. The result was the publication of Brittania (1586) a topographical and historical survey of, all

Great Britain and Ireland. The work was wildly popular and ran to many editions,

with Camden adding more material throughout his life. In In 1593 Camden became

headmaster of Westminster School. He held the post for four years, but left

when he was appointed Clarenceux King of Arms. By this time, largely because of

the Britannia's reputation, he was a well-known and revered figure, and the

appointment was meant to free him from the labour of teaching and to facilitate

his research.

William Camden, attired for his

Royal duties as the Clarenceux King of Arms, during the funeral procession of

Elizabeth the first. Wikimedia commons.

With so many editions and

reprints of these editions and the additions and amendments that Camden made

himself it is difficult to know what Camden’s original Latin text was. I

believe the closest to the original reads:

In huius sinus occidentalem angulum frome nobile huius tractus flumen

evolvitur, sic vulgus dicit, Anglo-Saxones vero, teste asseiro, frau dixerunt,

unde fortasse cum sinus ise Fraumouth olim diceretur, crediderunt posteri Frome

esse flumini nomen. fontes hoc habet ad Evarshott prope occiduum huius

comitatus limitem, unde in ortum aquas agit per Frompton, cui nomen impertiit,

et rivulum a septentrione admittit per cerne monasterium defluentem, quod

aedificavit Augustinus ille Anglorum Apostolus cum Heil gentilium Anglo-Saxonum

idolum ibi comminuisset, superstitionumque tenebras fugasset.

Translation:

Into the west angle of this bay

falleth the greatest and most famous river of all this tract, commonly called

Frome, but the English-Saxons, as witnesseth Asseruis, named it Frau, whereupon,

perhaps for that this bay was in old time called Fraumouth, the posterity

ensuing tooke the rivers name to be Frome. The head thereof is at Evarshot neere

unto the west limit of this shire, from whence he taketh his course eastward by

Frompton, whereto it gave the name, and from the north receiveth a little river

running downe by Cerne Abbay which Augustine the Apostle of the English nation

built when he had broken there in peeces Heil,

the Idol of the heathen English-Saxons, and chased away the fog of paganish

superstition.

A second translation of the same

portion of the text, translated into English by Gibson (1695) reads:

Into the west corner of this bay,

Frome, a famous river of this county, dischargeth itself; for so 'tis commonly

call'd, tho' the Saxons (as we learn from Asserius) nam'd it Frau, from whence

perhaps, because this bay was formerly call'd Fraumouth, latter ages imagin'd

that the river was call'd Frome. It has its rise at Evarshot, near the western

bounds of the shire, from whence it runs Eastward by Frompton, to which it has

given its name, and is joyn'd by a rivu∣let from the north that flows by

Cerne Abby, which was built by Augustin the English Apostle, when he had dash'd

to pieces the Idol of the Pagan Saxons there, call'd Heil, and had reform'd their superstitious ignorance.

The use of the phrase “as

witnesseth Asseruis”, initially made me excitedly, think that during his

antiquarian travels, Camden must have located and read a text of which I was

unaware or lost. In a way, I was right on both counts.

It seems that original text that

Camden used to construct his section Descriptio

Angliae et Walliae subs. Dorsetshire

in Britannia, was by the ninth and

early tenth-century Welsh Bishop Asser of St. David’s and Sherborne. The text

was known as Vita Ælfredi regis. This document was in the

collection of Sir Robert Bruce Cotton of Ashburnam House, London until a fire

destroyed it, in 1731 and was known as “Cotton Otho A.xii”.

Luckily the manuscript had been

previously copied by Matthew Parker and printed (1574). As Martin (2016) points

out “Camden's edition, as it is derivative almost entirely from Parker's

printed text” and “Whether William Camden knew it or not, by reproducing

Parker's edition almost wholesale, he was producing an edition that would be

steeped in Parker's ideological conceits.”

Three interesting facts emerge from these two texts. Firstly the use

of a different name for the Anglo-Saxon deity worshipped at Cerne Abbas: Heil.

Secondly this is the first time

we have seen any claim possibly relating to the removal of the Cerne Abbas

Giant: “he had dash'd to pieces the Idol of the Pagan Saxons there”. This

claim, however, may just be an embellishment of Camden’s or his translator,

Gibson (1695).

Lastly, the claim that Cerne

‘Abby’ was built by Augustin the English Apostle, is patently false, as the

Abbey was founded in 987 AD by Æthelmær the Stout a benefactor of the

Benedictines.

It is noteworthy that Richard Gough, editor of the 1789 edition of William Camden's 1637 work Britannica, linked the Giant with a supposed minor Saxon deity named by Camden as “Hegle”. This quote is drawn from Koch (2006).

My next source is Dr Richard Pococke the Irish Bishop, who visited Cerne Abbas saw the Cerne Giant in 1754. His account is recorded in a secondary source by Brayshay (1996): “In October 1754, Bishop Pococke again visited Dorset.. He described the town of Cerne Abbas as: ‘a large poor town being nearly a mile in circumference. They make malt, and are more famous for beer than any other place in this country; they also spin for the Devonshire clothiers. Pococke made brief notes on the site of the Abbey and the few standing remains that were visible. Finally, he described the Giant: ‘A low range of hills ends to the north of the abbey, on the west side of which is a figure cut in lines by taking out the turf showing the white chalk. It is called the Giant and Hele, is about 150 feet long, a naked figure in a genteel posture, with his left foot set out: it is sort of a Pantheon figure. In his right hand, he holds a knotted club; the left hand is held out and open, there being a bend in the elbow, so that it seems to be Hercules, or Strength and Fidelity, but it is with such indecent circumstances as to make one conclude it was also Priapus. [in other words it had a large erect penis] It is supposed that this was an ancient figure of worship, and one would imagine that the people would not permit the monks to destroy it. the lord of the manor gives some thing once in seven or eight years to have the lines clear’d and kept open.’

Next I come to a report on a lecture given by Stukely (1764) and

appended to Hutchins (1774), reads thus: “Dr. Stukeley read, and delivered in,

a minute of the observations made by him on the Giant of Cerne Abbas, in

Dorsetshire, read to the Society the 16th of February last. He observes it is

an immense figure of an Hercules, armed with his club, cut out of the turf of a

sloping chalk-hill. It required a good share of skill in opticks to make it

appear with any tolerable degree of symmetry in that situation…

Stukely, went on to discuss the possibility that the Cerne Giant

represented the Phœnician Hercules.

The great British King Eli, surnamed Maur, and the Just, father of

Imanuensis, King of the Trinobantes, and of Cassevelan, [Cassivellaunus was a powerful warrior king of the Catuvellauni tribe] who headed the

Confederate Britons to oppose Caesar in his invasion of Britain, is intimated,

the Doctor thinks, in this figure of the Giant at Cerne Abbas, to which the

people there give the name of Helis.”

Incidentally Castleden (1996) quotes Stukely as remarking “Stukeley suggested that “local people know nothing more of [the Giant] than a traditionary account of its being a deity of the ancient Britons”. Perhaps Stukely should’ve delved more deeply into the local lore during his 1723 visit.

This source also appears as an

appendix to my next source.

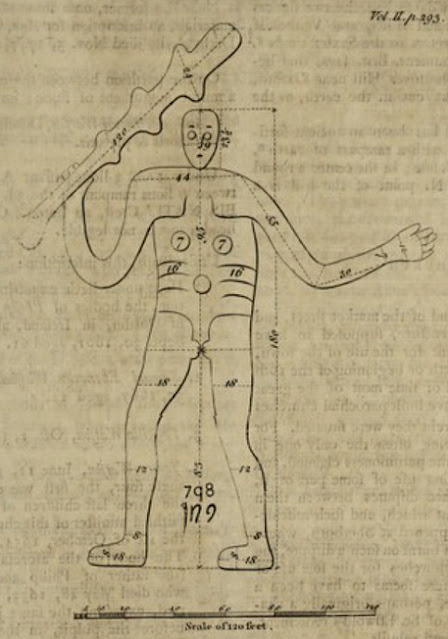

The next source I need to bring to light is Hutchins’ The History and Antiquities of the County of Dorset (1774). In the context of the Cerne Giant, this book is notable for its first, widely available, illustration of the Giant.

An image of the Cerne Giant

by Hutchins, from the Gentleman’s Magazine (1764). This version clearly shows

the Giant’s penis, with his glans clearly connected to the penis shaft. This is

a clear contradiction to the belief of modern archaeologists, that the Giant’s vital organ has become ‘more

engorged’ over the centuries and engulfed his navel.

A ‘censored’ version of the which was printed in Hutchins (1774). Notice the penis is missing but the letters between the Giant’s feet are shown.

With direct reference to

the Cerne Giant Hutchins states: “On the south side of a very steep

hill, called Trendle Hill, a little N. of the town, is the figure of a giant,

cut in the chalk; his left hand is extended, and his right erected holding a

knotted club. The outlines are two feet broad and as many deep. Between his

legs are certain rude letters scarce legible given here as copied Aug. 1772. It

is plain there were never more than three.” [here Hutchins (1774) records the

dimensions of the Giant in a table]. He goes on:

“Some affirm them to be a proof of the great antiquity of the figure,

which they refer to Saxon times. Over these are three more figures probably

modern. If these are intended for a date, we may read 748, and suppose the

figure represents prince Cenric, son Guthred king of Wessex, who was killed

that year. The Saxon Chronicle and Florence of Worcester do not say on what

occasion, or where. If they are to be taken as to be a modern date of repair

(perhaps 1748), and the letters below do not stand for Ano, might we, without a Stukelian conjecture read the word IAO,

and suppose the figure to represent the supreme Deity?

It has been reported to have been made by lord Holles’s servants,

during his residence here: but it is more likely that he only caused it to be

repaired; for some people who died not long since, 80 or 90 years old, when

young knew some of the same age, that averred that it was there beyond the

memory of man.

There is a tradition, that a giant, who resided hereabouts in former

ages, the pest and terror of adjacent country, having made an excursion to

Blackmore, and regaled himself of several sheep, retired to this hill, and lay

down to sleep. The country people seized this opportunity, pinioned him down,

and killed him, and then traced out the dimensions of his body, to perpetuate

his memory. Fabulous as this story is, it is perhaps proof of the great

antiquity of this figure. It extends over near an acre, as does the White Horse

of Berkshire, which is 150 feet from the head to the withers. It seems to have

been executed by persons who were not unacquainted with the rules of proportion

observed by statuaries and painters, who anciently allowed seven or eight heads

to the length of the human body. It is repaired about once every seven years by

people of the town, by cleaning the furrows, and filling them with fresh chalk.

Scouring the White Horse a custom and festival solemnized from time immemorial,

by a numerous concourse of persons from the adjacent villages. If there ever

was a particular day in the year for this purpose here, the memory of it is now

lost, and the operation performed just when the towns-people think fit. Most

antiquaries think that is a monument of high antiquity, and make little doubt

but that it was a representation of the Saxon god Heil; fo that it must be more

ancient at least than 600 A.D., soon after which time the Saxons were converted

to Christianity.

Dr Stukely was of singular opinion, that it was the figure of

Hercules, and that the Saxon god Heil was no other than the Phœnician Hercules,

or Melicarus, who brought hither the first colony, and that this figure was not

so much an object of religious worship, as a memorial. The club in our giant’s

hand seems to have led him to imagine this. He supposes this enormous figure

might be cut by the Britons in compliment to Eli surnamed the Great,

on expelling the Belgæ. Here is a

wood called Hell-wood to this day.

The late learned Mr. Wise, who from an excess of delicacy declined to

illustrate this singular monument, supposes it of a much later date than the

two figures of white horses in Berkshire and Wilts, and Whyteleaf Cross Bucks,

which he refers to Saxon times. Mr. Aubrey, in his Monument. Brit. says that

before the civil wars, on Shottover Hill near Oxford, was the effigies of a

giant cut in the earth, as the White Horse is.

On the top of the hill has been

an ancient fortification, 110 feet square, with a rampart of earth, and a ditch

only on the N. side; in the centre area hollowed. On the N. point of the hill

is a barrow.”

This text throws up a,

number of, interesting questions:

- First, Hutchins’ link of the Trendle to maypole erection, is an interesting point as it links the site to residual pagan celebrations, which continued to within living memory

- The maintenance of the figure, throughout the centuries, and the record of the letters between the Giant’s feet shows that it was still held in reverence by the local people and was a ‘living figure’ in that to some other group (Churchmen?) it was still an irritant that needed annotating

- The sentence “It has been reported to have been made by lord Holles’s servants, during his residence here.” What Hutchins didn’t realize was that by simply stating this rumour, he had start a string of suppositions that persist to this day. Modern phrases like ‘urban myth’, ‘conspiracy theory’ and ‘fake news’, spring to mind. This is a second subject I’ll return to later.

- From the memory of local octogenarians and nonagenarians, we can calculate a date for the time when the giant was constructed at a minimum. 1774 – [10 years for people that ‘died not long since’ (+ 80 x 2) + 2 more generations for ‘beyond the memory of man’ (80x2)] or 1774 - 330 years = 1444 AD as a minimum age.

- Hutchins’ recording of the 6 letters between the Cerne Giants feet open a window to the idea that the figure may have been subject to a drift in form or surrounding motifs, over time. This is a theme that I’ll examine when I look at later sources.

- Most antiquaries of the 16th century and earlier believed that the Cerne Giant was Saxon God Heil, with Hutchins putting the date of construction as 600 AD due to the Saxon pagans being converted to Christianity after this date. Unaccountably this sensible theory was almost utterly forgotten by the 20th/21st century. This is perhaps the most surprising fact of all!

The next source I want to

look at, is a much later one by March (1901). His article gives details of the

Giant and Maypole of Cerne. The maypole set up, every May 1st, in

the square enclosure or “Trendle” above the Giant’s head. He explores the history

of maypoles in both a European and local context and states that the Cerne

maypole was taken down in 1635, anticipating the Long Parliament’s ordinance of

April, 1644, that all maypoles were to be taken down.

However, it was

subsequently re-erected: “But, after the advent of Charles II., the maypole was

set up again and had a long life. Robert Childs, the present sexton, well

remembers it. “It was made,” he says, “every year from a fir-bole, and was

raised in the night. It was erected in the ring just above the Giant. It was

decorated, and the villagers went up the hill and danced round the pole on the

1st of May."

The fact just mentioned

deserves especial notice. Cerne had been a busy town, and had some sort of

market-place, as well as a village green. But the maypole was set up in neither

of these places, but nearly half a mile away, on the top of a very steep hill,

“in the ring just above the Giant." This ring is of a rhomboidal shape, an

approximate square, each side measuring about 120 feet, or according, to,

Hutchins, 110 feet.

On the

opposite side of the valley, on Black Hill, is another "square camp."

Two similar camps were excavated by the late General Pitt- Rivers, and of these

that at South Lodge is 150 feet square and that on Handley Hill 108 feet

square.

No iron was found in them,

but bronze implements and weapons in abundance, with tools of horn and flint,

and fragments of pottery that revealed a continued occupation into Romano-British

times. Now, if exploration has assigned such rhomboidal camps to the Bronze

Age, it has proved with equal certitude that a very large proportion of the

barrows of Dorset also belonged to that period of civilization.”

March now turns to the

topic of the Giant, he goes on:

“Has the Cerne Giant a like

affinity? Or is it mediaeval, or even modern? But it cannot be modern, because

William Stukeley described it as ancient in a paper, not hitherto published, but

now given as an appendix, which he read to the

Society of Antiquaries in 1764. Footnotes: The Cerne Giant is not mentioned by Stukeley in his works, “Itinerarum Curiosum” 1724; “Palseographia Britannica” 1743; “Itinerarum Curiosum Centuria” 1776.

“And, assuredly, few

persons can believe that it is mediaeval, the work of monks, though they failed,

or were not permitted, to demolish it. Probably they pointed to it as a symbol

of the Paganism that Christ came to subvert, and were content to put their mark

upon it, as they would carve a cross on a cromlech, to arrest its power for

evil by means of a holy signature, which Hutchins saw in August, 1772, and

carefully copied (see figure C).”

March’s Figure C – the letters formerly between the Giant’s feet. Figure D is a True Ray, probably a Skate, the tails of which were allegedly pinned to Augustine and his followers backs by the inhabitants of Cerne around AD 900.

On the question of the

letters formerly between the Giant’s feet March says: “The figures can hardly

form part of a date. They are not Roman numerals, and Arabic letters were not

introduced until the XV. century. The formula, I.H.S., was also of late

introduction, and would be altogether inappropriate.

The Giant has usually been repaired

every seven years, and was last set in order in 1887 by Jonathan Hardy, now 69

years of age, under the direction of General Pitt- Rivers. It is difficult to believe

that the original form of a signature has been exactly preserved by those who

were totally unacquainted with its meaning.

Speculation, therefore, though easy, is unsafe. But of the letters that were drawn by Hutchins, the first is J. ; the second precisely resembles the sign for Saturn in use prior to the XIV. century or it may be H. ; and the third may be D. So that the signature would read : Jehovah [or Jesus], Saturnum [or Hoc] Destruxit, God has overthrown this idol [or Saturn]. Saturn was the god of agriculture and growth, the devourer of his own children, the fabled author of circumcision, who bore an implement in his right hand, whose festival was celebrated with riotous merriment, and to whom human sacrifices were offered. Combined with such a conceit may have been a monkish play on the word Satan.”

The penultimate source I want look at is Lethbridge (1957). T. C. Lethbridge (1901-1971), was an English archaeologist

and parapsychologist. A specialist in Anglo-Saxon archaeology, he served as

honorary Keeper of Anglo-Saxon Antiquities at the Cambridge University Museum

of Archaeology and Ethnology from 1923 to 1957. He claimed that Iron Age hill

figures existed below the turf, at Wandlebury Hill on the Cambridge chalk

downs. His excavations there caused significant controversy within the

archaeological community, with most archaeologists believing that Lethbridge

had erroneously misidentified a natural feature as a group of hill figures.

Lethbridge's methodology and theories were widely deemed unorthodox, and in

turn he became increasingly critical of the archaeological profession. After he

published Gogmagog The Buried Gods in 1957, his career ended abruptly. He was dismissed

from his post after quarter century of diligent work at Cambridge university.

Lethbridge’s book describes his

excavations at Wandlebury in detail. These culminated in a vast tableau of

figures emerging from the chalk turf. He backs up his work with research into

local history and folklore and concludes that the three figures are an Iron

Age. In the second part of the book he attempts to synthesise what is known of

the hill figures of Britain. This

thoughtful and wide-ranging literature review naturally included the Cerne

Abbas Giant.

Lethbridge however, is not

satisfied with these written, primary and secondary sources and consults aerial

photographs of the Giant. Whether these were connected to those collected by

the Royal Airforce during World War II, I have been unable to ascertain.

Whatever their source, Lethbridge was (as far as I am aware), the first person

to note the presence of a cloak, descending from the Giants left arm. Even more

interestingly was the fact that, by his careful examination of these aerial

images, he came to believe that a second figure could be discerned further out,

beyond the Giant’s cloaked left arm.

Hand-drawn sketch by Lethbridge (1957) of the cloak and possible

second figure on Trendle Hill, Cerne Abbas. Original caption reads: Fig. 12 - Sketch

composed from the study of several air-photographs and direct observation of

the Cerne Giant. This shows lines which must almost certainly be a missing

cloak and others which may indicate a second figure. (This is a freehand sketch

and not a measured drawing).

Whether these faint marks on the

hillside are actually the remains of another chalk-cut figure or figures is

hard to judge. One thing is certain however, the ‘cloak’ especially has

generated a lot of interest as seems more than plausible. In fact, many an

account or blog posting mentions it, without giving any source reference. The

faint outlines of the possible, second figure is never mentioned by academics

or archaeologists. I find that sad and quite telling, in terms of Lethbridge’s

reputation in the world of archaeology today.

The final source I want to look at is surprisingly not an academic

one, nor is it data collected by an archaeologist. Instead I am going to cite a

‘citizen scientist’. In an article in The Independent by Gillie (1994) claims

were made that marks below the Cerne Giant’s left had represent a severed human

head. Excerpts from the article:

“The Cerne Abbas giant, a naked relic of ancient British heritage, may

once have worn a cloak over his shoulder and carried a severed head in his left

hand. New studies of the soil around the giant have found disturbances which

suggest that the figure has changed considerably since it was cut into the

chalk of a Dorset hillside about 2,000 years ago.

Rodney Castleden, an independent archaeologist who is head of

humanities at Roedean School, near Brighton, has spent two years studying the

figure. With the help of the physics teacher, Michael Ertl, he built an

electrical apparatus similar to that used by the police to search for bodies.

'The apparatus measures electrical resistance of the soil. A high

resistance shows that the soil has been disturbed,' Mr Castleden said. 'The

readings have been consistent from year to year and show a lot of disturbance

under the giant's left arm. The lines I have found could represent a cloak or

animal skin which was a common feature of figures that have survived from this

period.'

Evidence of soil disturbance suggests that the figure may have had

additional features which have been lost. A small knoll, some 40cms high, under

the left hand could once have been a representation of a severed head, Mr

Castleden believes.

Mr Castleden's studies have not only raised new questions about the

giant, they have also settled some old controversies. During Victorian times

the giant's penis became discreetly veiled by the natural growth of shrubbery.

Scholars believe that when the penis was subsequently re-excavated it was

extended by some two and a half metres. This has now been confirmed.

'Originally the giant had a navel but it became incorporated into the

phallus when the figure was recut. I have made a trial run down the phallus and

obtained electrical measurements indicating a join,' Mr Castleden said. 'The

phallus is probably not part of a fertility cult as some scholars have

suggested. Figures were often depicted in this period with an erect phallus and

it was probably seen more as a sign indicating good luck or prosperity.'

'A severed head would fit with an Iron Age god, a guardian of the

tribe returning from battle with the head of an enemy. The figure is in the

centre of territory once occupied by a tribe called the Durotriges, an area

which is roughly equivalent to present day Dorset. There is an ancient holy

well near by. The Celts were keen on sacred springs and so it is an obvious

place to create an image of a guardian God,' he said.

Mr Castleden is meeting with the

National Trust, which owns the site, and the county archaeologist in August to

consider whether they might undertake a small excavation of the site. The trust

will then have to consider the delicate question of whether to restore the

penis to its proper length and whether, or not to cut back the turf to reveal

the cloak and any other items that are confirmed by excavation.

This investigation, despite being

carried out by a non-professional, has garnered a great deal of interest. Again,

as with the Lethbridge observations, one part of the story, that of the severed

head, has entered into modern folklore, almost as fact. The other details

however, were completely ignored. Additionally, the origin of the data, which

may, or may not indicate the Cerne Giant holding a grisly trophy, is never

given.

Concluding thoughts

1. Contrary to scholarly opinion,

there are sources going back to the end of the 6th century (Augustin

of Canterbury via Goscelin), that mention Pagan worship of a deity at Cerne

Abbas.

2. The first mention of the hill

figure cut into the turf at Cerne Abbas, goes back to Wise (1742). However, the

legend that Lord Holles’ servants cut it clearly indicate the Cerne Giant was

extant in around 1642. My calculation derived from Hutchins indicate that the

figure was in existence before ca. 1440 from the memories of local villagers.

3. The Pagan God worshipped at

Cerne and the hill figure, was variously known as Heliae, Helio, Heil, Helith,

Hele, Hegle and Helis. If we

think of the Christian concept of the Trinity, the unity of Father, Son, and

Holy Spirit as three persons in one Godhead, may it not be possible that the

Saxon pagans venerated a God with different aspects and thus, different names?

Goos (2013), delves into the

possible meanings of these names. His section on etymology is so thorough, I

repeat it here with but light edits:

Heliae

There are several possible origins for this variation of the deity’s

name;

The biography of the Carmelite monk Robert Bale, native from Norfolk,

England, who died in 1503, carries the title: “Historia Heliae Prophetae”. Heliae is also the Roman form for

Elijah, which originally is derived from Greek Helios. It is unlikely though this

meaning is meant here, because a heathen Anglo-Saxon deity hardly would be named

after a Greek word for sun.

Helio is supposedly a correct modern translation if the Latin HELIAE.

Connecting that to Old English, it might point to

hÚ-l u, hÚ-l-o, which means health, fortune, wealth, safety,

deliverance; or to héa lic, excellent, strong, lofty. But it is also possible

that it points to ‘Helia‘ as nouns ending with an ‘a’ are in Old English

masculine.

It is possible that ‘HELIAE’ is an ecclesiastical Latin form for an

Old English name. Perhaps the most likely is that it is a corruption of Old

English hæle: ‘man, brave man, hero.

It could derive from the Middle English word heil which is defined as

below:

heil (a) Health, welfare,

good fortune; in quert and ~, whole and sound;

heil (b) a person’s health or good fortune drunk to with wine; drinken..~, to drink (a person’s) health.

Helið

This variation would seem to have a couple of possibilities as to what

it is derived from. It may derive from or related to Old English hæleþ which

is defined as follows.

hæleþ, heleþ, es; m. A man, warrior, hero [a word occurring

only in poetry, but there frequently]

Additionally, the Old-Saxon helið derives from

proto-Germanic *haluð- which means Hero, warrior, free man.

It could be related to Middle English hél which is

defined as follows:

hél (a) Healthy, cured (b) in good condition, prosperous (c) whole, complete.

Helith

Helith is simply a variation of Helið being the

modern version of the Middle English name.

Helid-, Cald-OHG. helith,

helidh, helid = hero in the meaning of strong, powerful, outstanding,

lofty, sublime, tall..

Hel(e), Heile

Hel(e), Heile is most likely related to Old English hál which

is defined below.

hál ; adj. Whole, hale, well, in good health, sound, safe,

without fraud, honest; often used in salutation

It evolved into Middle English as hél (see definition

above). Hál is related to the following Old Saxon words hê-l and hêl which

could have been drawn on by the Middle and early modern English authors for the

name.

a. hê-l* OS.,

sign, omen, OHG. heil Germ. *haila-, *hailam, hail, luck,

omen, MND. hêil

b. hêl OS., Adj.: hail, healthy, uninjured, whole

(Adj.); anfrk. *heil; Germ. *haila-, *hailaz, Adj.,

healthy, unhurt; idg. *kailo-, *kailu-, whole.

In 1764 William Stukely wrote

that people in the area called the Giant “Helis”. Another writer stated that up

until the 6th century, the god Helis was worshipped. Helith and Helis may be

bastardisation of the ancient version of the name for HERCULES – HETETHKIN, a

not verifiable name for a ‘local Hercules’.

Goos (2013) finishes with the

conclusion: “Almost all of the words that these names possibly come from

PIE *kailo- “ whole, uninjured, of good omen” which gave us

our words ‘holy,’ ‘heal,’ ‘health,’ and ‘hail.’ As to what form the original

name of the deity took and which word the original name derived from is

anyone’s guess. The earliest form given is Heliae, but Helith would seem to be

the most common form, and as the text is in Latin Heliae may be changed a great

deal from an Old English original.”

Here I diverge from Goos, as it may be that as mentioned earlier, the

Saxon God worshiped in the region, and possibly more widely in southern

Britain had a, number of, aspects woven into one. Thus, the local Pagans may

have given answers analogous to: the Lord God, Jesus, the son of God, the Holy

Father etc. It is also known that Augustine, at least spoke through

interpreters. It is not unreasonable to suppose that some of the subtleties may

have been lost in translation.

I would therefore add, strong,

hero, fortune and deliverance to the root meanings of the Saxon deity’s name.

4. Scholars agree that as there

is no direct evidence of the Cerne Giant existed prior to 1642. In a

contra-argument I bring forward the actions of none other than the Christian

church. The Abbey was founded in 987, approximately 400 years after the Saxon

tribes of the region had been converted to Christianity.

The first abbot, Ælfric of

Eynsham is regarded by Blair (2003) as "a man comparable both in the

quantity of his writings and in the quality of his mind even with Bede

himself." The reasons that the Catholic Church in England appointed one of

its rising stars to be the abbot of a small, remote abbey in far-flung Dorset

bears, looking into.

Ælfric, is justly famous as a prolific writer in Old English of

hagiography, homilies and biblical commentaries. This facility as it pertains

to our exploration of the origins of the Cerne Abbas Giant centres on a sermon

he gave, while abbot entitled De falsis

diis, ('on false gods'). The sermon is noted for its attempt to explain the

traditional Anglo-Saxon beliefs within a Christian framework through Euhemerization.

Although Ælfric's sermon was based

to a large degree on the sixth-century sermon De correctione rusticorum by Martin of Braga, the themes it seeks

to address gives us a window into the extant beliefs of British Anglo-Saxons in

the late 10th century.

In the sermon he preaches that the

worship of natural elements, (“Animism”), the worship of the sun, the moon,

stars, fire, water and earth as gods, were the teachings of the devil. The only

conclusion one can draw from the construction and delivery of this sermon is

that animism was widespread and long-lasting. In fact, although the church was

always working towards the destruction of heathen practices, change came about at

a variable rate and with differing success. It seems that the people of Cerne

and of the populance more widely across England, were not willing to quickly

abandon the customs and traditions their people had had for generations. Therefore,

Ælfric must have felt that there was acute need in his local congregation, to

rebut their lingering pagan beliefs, by way of his sermon.

I therefore, believe the Giant

was extant on the hillside above Cerne Abbas, at this time and furthermore that

the Church did what it always did with problems it couldn’t solve: ignore them.

Recall the recent child abuse cases within the Catholic Church. Alternatively,

this could have that period identified by Allen (2020) when the Cerne Giant was

grassed over.

Lastly on this topic, I want to

address the ‘Why’ question, by which I mean why did the local Saxons (if it was

them), construct the Cerne Giant?

A very thoughtful article in The

Independent by Keys (2021) may provide may provide an answer as to why the Saxons of 7th century

created the Cerne Abbas Giant. I have taken the liberty of editing his text

lightly, for the sake of narrative consistently:

“That was one of the most important periods of English history was the

mid-to-late 7th century.– the era that witnessed much of the Anglo-Saxons’

transition from paganism to Christianity. The cultural and political struggles

that accompanied that transition were often accompanied violence as the two

ideologies grappled for the soul of the Kingdom.

The transition from paganism to Christianity was a politically fraught

and often an antagonistic process during which traditionalists – loyal pagans

sometimes ostentatiously championed their cause.

It is therefore conceivable that the vast hillside artwork was created

during one of two local pagan resurgences which occurred between AD642 and 655

and again between AD676 and 685.

The Cerne Giant is, located in, what was the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of

Wessex. Initially, that kingdom’s joint rulers converted to Christianity in 635

– but one of them died soon after and, when the surviving one died seven years

later, his son reverted to paganism.

In the 640s and early 650s, Wessex was conquered and controlled by

England’s most powerful pagan ruler, the king of the Midlands-based Mercia.

Christianity temporarily returned to Wessex, and was snuffed out again between

676 and the early-to-mid 680s. But by 685, Wessex was Christian again – and indeed launched a genocidal campaign

against pagans on the neighbouring Isle of Wight.

Although the Cerne Giant was conceivably an expression of pagan

reaction to Christian pressure, it is certain that the local population

continued to venerate the vast figure for several centuries (see comments on Ælfric above).

Indeed, there are medieval and Tudor accounts of legends suggesting that the people of Cerne were loyal devotees of a great pagan deity or idol, apparently known as Helith, Heil or Helio (which would broadly translate as “powerful hero”). It is therefore possible that that deity, idol or venerated “hero” was indeed the great hillside giant.”

The Cerne Giant as an English Civil War ‘joke’

The suppositions that the Cerne Abbas Giant was created in the 17th century depend on the word of one man. This theory originated in the 18th century account of John Hutchins, who noted in a letter of 1751 from John Hutchins to the Dean of Exeter that the steward of the manor had told him the figure “was a modern thing, cut out in Lord Hollis' time.” However Hutchins (1774), also suggested that Holles could perhaps have ordered the recutting of an existing figure.

Lord Holles ca. 1640 by Edward

Bower. Wikimedia commons.

It has been speculated that

Holles could have intended the figure as a parody of Oliver Cromwell: while

Holles, the MP for Dorchester and a leader of the Presbyterian faction in

Parliament, had been a key Parliamentarian supporter during the First English

Civil War, he grew to personally despise Cromwell and attempted to have him

impeached in 1644. Cromwell was sometimes mockingly referred to as

"England's Hercules" by his enemies: under this interpretation, the

club has been suggested to hint at Cromwell's military rule, and the phallus to

mock his Puritanism.

Other unfounded/unsourced stories

and theories, proliferated in this early era of antiquarians, and right down to

the present day. Briefly these are:

- That Lord Holles’ servants cut the figure of the as a representation of Denzil Holles himself. “A further tradition local to Cerne was that the Giant was created by Holles' tenants as a lampoon aimed at Holles himself.” Castleden (1996),

- Another 18th century writer dismissed it as "the amusement of idle people, and cut with little meaning, perhaps, as shepherds' boys strip off the turf on the Wiltshire plains." (from Castleden (1996)).

- Harte (1986) theorises, from local stories (source unknown), that the Giant was cut in 1539 at the time of the Dissolution of the Monasteries as a "humiliating caricature" of Cerne Abbey's final abbot Thomas Corton, who amongst other offences was accused of fathering children with a mistress. The erect penis it was said, represent Corton’s lustful ways, the club his vicious tendency in revenge when slighted and his feet pointing away from the village that he had justly been cast out.

- The Heritage Gateway website (2012) stated that Cerne Giant may have been of Celtic origin. They compare the Giant stylistically to a representation of a Celtic god (Nodens) on a skillet handle found at Hod Hill, Dorset. The handle almost certainly dates from between AD 10 to AD 51. From this the theory is put forward that the Giant dates approximately the same period as the handle and was made by the Durotriges [tribe] to represent a god of fertility and hunting. Their original source is unknown.

- Piggott (1938) developed the theory that due to the giant's resemblance to Hercules, it is a creation of the Romano-British culture, either as a direct depiction of the Roman figure or of a deity identified with him. It has been more specifically linked to attempts to revive the cult of Hercules during the reign of the Emperor Commodus (176-192), who presented himself as a reincarnation of Hercules: Castleden (1996).

Whether any of these suppositions held any grain of truth was unknown, maybe the Cerne Giant would turn out to be Iron Age? Maybe it was Bronze Age, like the Uffington Horse? Or could it be Medieval as the vast swathe of collected information from the late 7th to the 18th century seemed to indicate? This last possibility, seemed to present-day archaeologists most unlikely. So, everyone waited with baited breath for the results from the Optically Stimulated Luminescence results of Martin Papworth and team.

The last thing I would like to point out, is that the earliest known written reference to the Cerne Giant, is a 4 November 1694 entry in the Churchwardens' Accounts from St Mary's Church in Cerne Abbas, which reads "for repairing ye Giant, three shillings” (see Darvill et al. (1999)).

The fact that the church was now

paying for repair of the Cerne Giant is extremely surprising as for centuries

they had been intent on eradicating all vestiges of paganism and its symbols.

Even more surprising is that this fact is passed over by every researcher on

the subject I have read.

This apparent reverse in policy

is contained within the phrase “the church” above. It wasn’t the same church of

course! During the reign of Henry VIII, due to the Catholic Church’s refusal to

allow him annul his marriage to Catherine of Aragorn, Henry broke with the

Catholic Church. This period in history is known as the Reformation. Henry past

the act of Succession and the Act of Supremacy, which essentially declared

himself the supreme head of the Church in England. Thus the Church of England

was formed.

After Henry’s death, Protestant

reforms made their way into the church during the reign of Edward VI. But, when

Edward’s half-sister, Mary, succeeded the throne in 1553, she persecuted

Protestants and embraced traditional Roman Catholic ideals.

After Elizabeth I became queen in

1558, however, the Church of England was revived. The Book of Common Prayer and

the Thirty-Nine Articles of Religion became important texts that outlined moral

doctrine and worship principles.

The Puritan movement in the 17th

century led to the English Civil Wars. During this time, the Church of England

and the monarchy were quelled, but both were re-established in 1660, with the

re-establishment of the monarchy under Charles II.

However, political turmoil once again engulfed England upon Charles’ death as he had no legitimate offspring. Therefore, his brother James II of England and James VII of Scotland took the throne. His reign is now remembered primarily for struggles over religious tolerance. In June 1688, two events turned dissent into a crisis; the first on 10 June was the birth of James's son and heir James Francis Edward, threatening to create a Roman Catholic dynasty and excluding his Anglican daughter Mary and her Protestant husband William III of Orange from the line of succession. Thus, parliament invited William of Orange to assume the English throne; after he landed in Brixham on 5 November 1688, with an army of 14,000, James's army deserted, and he went into exile. With the Bill of Rights passed in 1689, no Catholic could hold the English throne, nor could they marry one and henceforward the Church of England held sway.

Since the 16th-century Protestant Reformation, and ‘Glorious Revolution’ of 1688, the Church of England saw itself as the successor to the Anglo-Saxon and medieval English church. While the thoughts of the Church hierarchy went unrecorded in the matter of promoting the nation’s common Anglo-Saxon heritage, their actions speak louder than their unrecorded words: they encouraged and in the case of the Cerne Giant paid for repair of, any link back to our Saxon ancestors. Thus the scouring of the Cerne Giant, and many other public occasions were reinvented as descending from Saxon Merry England alongside the post-Restoration reintroduction of festivals dislocated from religion by the Reformation, and banned from the churchyard by Puritans.

As Edwards (2005) theorises:

“Whatever the actual origin of the Cerne Giant, the churchwardens of 1694 would

not be paying for the refurbishment of the figure unless its believed identity

conformed to church beliefs. The church authorities would not have been paying

for the restoration if they thought the figure's origin (as now commonly

considered) was Pagan Celtic, Roman Catholic, a Roman Hercules, or a cartoon

Cromwell.”

The true date of construction of the Cerne Giant

Martin Papworth (2021b) presented

the team’s results on his blog after the press release:

“In the end there were 5

Optically Stimulated Luminescence dates. Each from a different soil sample

selected from stratigraphic layers.”

The fourth sample came from the lowest chunky chalk layer which fills a cutting through the earliest hollow scraped into the natural chalk. The mid date for this is late 10th century, about the time that Cerne Abbey was founded. However, at the earliest it could be mid-7th century (but the 5th sample shows that it cannot be that early) and the latest early 14th century. Here are his section drawings with OSL sampling points marked:

Papworth

(2021b), showing the location of the earliest OSL dated sample. Original

caption: Trench C right elbow.

“The fifth and last date was taken from the colluvial soil that filled

the original cutting scraped into the natural chalk hillslope. This sample

yielded a central early 10th century date and had a more accurate date band

from the beginning of the 8th century to the beginning of the 12th century.”

Papworth (2021b) 5th sample: Trench B right foot.

Papworth continues: “What do we make of these data? Very unexpected.

It raises again the medieval references which talk of the locals of Cerne

worshipping a Saxon god Helith

before the Abbey was founded but this seems unlikely in 10th century

Dorset in a society which was largely Christian at that time..

The dates and stratigraphy seem to show a time of abandonment and then

recreation but this bottom chunky chalk layer is still medieval and still

potentially Saxon so we have to imagine the Giant and the Abbey side by side in

the landscape and perhaps he was used as a lesson in the landscape by the

monastic community.

He may have worn trousers then as our LiDAR shows the continuation of

the belt across the penis and we might suggest that his most noticeable asset

was created in the later 17th century when puritanism was on the wane.”

He may have been hidden after the Dissolution of Cerne Abbey after 1540 when brightly decorated interiors of medieval churches were whitewashed over.”

To me, Papworth and Toms’ most interesting results were those from sample 4, giving a date range of 650-1310 AD. These fit nicely with Keys (2021) Saxon resurgences of 642-655 and 676-685 AD. Although Papworth points out that the OSL date of sample, whilst giving the oldest date range, is unlikely to be correct, I have a serious question regarding this interpretation. As sample 5 “was taken from the colluvial soil that filled the original cutting scraped into the natural chalk” and the layer above was a “chunky chalk layer” it may be possibility that colluvium infiltrated through the interstices in these blocks. Therefore, a younger date for the lowest sample, number - 5 - is a possibility due to this migration of sediment. Consequently, the sample from slightly higher: sample 4, dated >650 AD, may be of a more accurate age for the creation of the Cerne Abbas Giant.

Nowadays with the hullabaloo of these dramatic results receding,

journalists far less frequently approach the worthies of Cerne Abbas for their

comments on the age of their Giant, which archaeologists brought forth from the

earth. In early morning one can view him alone, from the little carpark on the

A352. His eyes look away from you, up the valley, as if cogitating on far away

thoughts. Is it possible he is remembering the day when the Saxon populance

gathered to joyously dig and immortalise his memory by tying him to earth?

References

Alston, G.C. (1909). Goscelin. In the Catholic Encyclopaedia. Robert Appleton Company, New York. At: New Advent: http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/06655a.htm accessed 01/08/2021

Asser, J. [Asserius Menevensis] (893). Vita Ælfredi regis Angul Saxonum. In Parker, M. (1574). Ælfredi regis res gestae. John Day, London. At: https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/pdf/b30321438 accessed 29/07/2021

BANR (British Archaeology News Resource), (2021). Cerne Giant – surprise date at: http://www.bajrfed.co.uk/bajrpress/cerne-giant-surprise-date/ accessed 22/07/2021

Allen, M. (2020). BBC interview: Cerne Abbas Giant: Snails show chalk hill figure 'not prehistoric', at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-dorset-53313064 accessed 23/07/2021

Blair, P. H. (2003). An Introduction to Anglo-Saxon England, 3rd edition, Cambridge University Press, p. 357.

Brayshay, M. (1996). Topographical Writers in South-West England. Exeter University Press, Exeter, p.86-87

Camden, W. (1586). Britannia. George Bishop, London.

Castleden, R, (1996) The Cerne Giant, Dorset Publishing Company, Isle of Purbeck.

Current Archaeology (2021). Investigating the age of the Cerne Abbas hill figure, at: https://the-past.com/feature/investigating-the-age-of-the-cerne-abbas-hill-figure/ accessed 22/07/2021

Darvill, T., Barker, K., Bender, B. and R, Hutton (1999). The Cerne Giant: An Antiquity on Trial. Cerne Abbas Churchwardens' Accounts 4th November 1694, reproduced from the Dorset County Record Office. OUP, Oxford p. 72.

Discover Magazine (2020). Tiny Snails Help Solve a Giant Mystery, at: https://www.discovermagazine.com/planet-earth/tiny-snails-help-solve-a-giant-mystery accessed 23/07/2021

Dorset Natural History and Antiquarian Field Club, proceedings (1901), vol. 22 p At: https://archive.org/details/proceedings22dorsuoft accessed 25/07/2021

Edwards, B. (2005). The Scouring of the White Horse Country. Wiltshire Archaeological & Natural History Magazine, vol. 98 (2005), pp. 90-127. At: https://archive.org/stream/wiltshirearchaeo9820wilt/wiltshirearchaeo9820wilt_djvu.txt accessed 04/08/2021

Gibson, E. (1695). Camden's Britannia newly translated into English, with large additions and improvements. At: https://ota.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/repository/xmlui/handle/20.500.12024/B18452# accessed 29/07/2021